“Judge Dredd” (1995) lacks nuance as it presents a 22nd century police state where Street Judges (cops) serve as judge, jury and executioner. But should that really be a knock against director Danny Cannon’s film? After all, police states throughout history – other than perhaps using euphemistic language — aren’t exactly sneaky about how they do things.

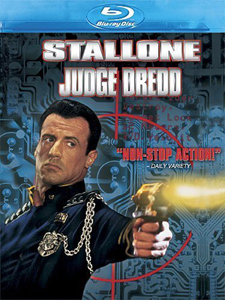

Stallone meets comics

Granted, this Sylvester Stallone vehicle — based on the character introduced in 1977 for the British “2000 AD” comic – isn’t particularly interested in exploring the hows and whats of the police state in the walled Mega City. But it does present the scenario evocatively enough that you can point to this film when people need an example of how authoritarianism functions at both street level and ivory-tower level.

Stallone plays Judge Joseph Dredd in broad fashion; at first, it seems the character is built around one-liners (“I am the law,” “Court’s adjourned”) more so than personality or backstory. He honestly seems mentally challenged.

“Judge Dredd” (1995)

Director: Danny Cannon

Writers: John Wagner, Carlos Ezquerra, Michael De Luca

Stars: Sylvester Stallone, Armand Assante, Rob Schneider

When comic relief/Everyman/audience surrogate Fergie (Rob Schneider, toning down his shtick to meet Stallone halfway) points out that Dredd being successfully framed is an example of the law being imperfect, Dredd’s facial expression shows that the idea never occurred to him before.

That’s not necessarily bad writing by William Wisher (“Terminator” and “T2”), Steven E. de Souza and Michael De Luca, though. We later learn that Dredd was grown in a vat; he’s precisely the tool the Council of Judges want.

Is this a sharp satire on modern American policing, wherein people with IQs above a certain level are not considered for the post? Maybe that’s giving too much credit to what is a Stallone actioner at heart, but it does soberly observe the direction of society.

Cannon adapts a comic before ‘Gotham’

“Judge Dredd” is by far the biggest film credit for Cannon, who went on to a standout TV career, notably helming many “Gotham” episodes. He’s the “good referee” equivalent of a director. We never notice his style, but he does the job well, keeping the action moving while also allowing the “Blade Runner”-esque locations and art design to shine; see the flying-bike chase that weaves through dark, downtrodden tenements.

The world-building is decent. The idea of a walled city, with outcasts living like primitives in the wastelands outside, is standard dystopian stuff, recently familiar to viewers of the “Divergent” saga. But at least we get to see outside the wall here, unlike in the truncated TV series “Almost Human,” a thematic cousin of “Judge Dredd” that portrays an authoritarian state in more detail.

One quibble I have is that we don’t get enough information that clearly tells us Dredd is the good guy and his brother, Rico (Armand Assante), is the bad guy. Functionally, all of the Judges are bad. This includes people like Dredd’s fresh-faced Street Judge partner, Diane Lane’s Hershey, even if the cinematic cues tell us she’s not villainous.

It’s well established that Dredd judges people too harshly and that he himself gets a lighter sentence (imprisonment rather than death, because Max von Sydow’s Chief Justice Fargo likes him) than any citizen would if caught in Rico’s frame job.

Rico’s revolution is – in and of itself – a justified takedown of an oppressive state. His goal (to grab power for himself) is not, nor are his methods (murders and frame jobs), so he’s certainly a bad guy.

Why is Dredd the good guy?

But why is Dredd the good guy? The film knows we will simply like Dredd and Stallone more, and decides that’s enough. It’s unclear if Dredd learns a lesson, but it is clear that he has no intention of turning himself in or asking for an internal review of his past judgments.

“Judge Dredd” includes its share of stupid little things. For example, the Council learns — by asking a central computer — that a fresh supply of Judges can be grown in vats in eight hours. (Armed with that new knowledge, they then grow some Judges in vats.) It’s bizarre that they wouldn’t already know that as a matter of course.

The murder frame-job on Dredd is a little simplistic for the future; it’s based on his DNA being the same as his brother’s. Since Rico has escaped from his cell, the clear legal defense would be to posit that Rico is the killer.

“Judge Dredd” does not hold up to a close analysis, and I look forward to listening to some movie-mocking podcasts about it. Nonetheless, the silly details don’t overwhelm the big picture.

“Judge Dredd’s” portrayal of the technology, philosophy and operations of a police state strike me as accurate more so than a funny exaggeration. (Maybe that’s the difference between watching it in 2020 rather than 1995.) That includes Stallone’s turn as Dredd, someone who exists to judge, not to think.