Like Joss Whedon loves penning dialog and Shane Black enjoys dodging action-movie cliches, David Wong (real name Jason Pargin) clearly has a blast writing insane sci-fi adventures starring “himself” and his fictional friends John and Amy.

As a piece of speculative fiction, “John Dies at the End” (2009) is a competent but not groundbreaking exploration of the multiverse theory, a subgenre that has dominated SF in the 21st century – peaking last year when “Everything Everywhere All at Once” won an armload of Oscars.

As a sheer exercise in fun, though, “JDATE” is so good that it plays as something fresh. Loaded with sardonic wit, the prose comes wholly from Wong’s heart and mind even though the plot and thematic influences are multifold.

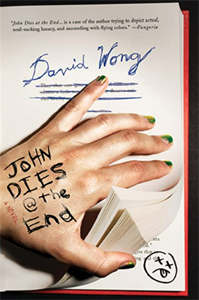

“John Dies at the End” (2009)

Author: Jason Pargin, writing as David Wong

Series: “John and Dave” No. 1

Genre: Comedic horror

Setting: “Undisclosed,” early 21st century

Note to readers: The Book Club Book Report series features books I’m reading for my book club, Brilliant Bookworms.

Adding monsters and multiverses to the mundane

David and John are a paranormal investigative duo that follows up tips on the web like the team from “Freakylinks” (2000-01). Amy Sullivan, David’s misunderstood but sweet one-handed girlfriend, becomes a third member of the ragtag team. A dog, Molly, rounds out Wong’s Scooby Gang.

David and John work in a video store in “(Undisclosed),” which context clues suggest is in Ohio. The mundane urban setting (including a mall that was closed and left to rot before it ever opened) calls to mind the Leonardo, New Jersey, of “Clerks’ ” convenience-store heroes Dante and Randal. A lot of the action takes place in a frigid, snowy winter.

Kevin Smith made “Clerks” with – and about – his friends. That’s what Wong does in book form. As with Smith, Black and Whedon emerged as cliché-dodging screenplay and teleplay writers not long before Wong started writing “JDATE” as a web serial in 2001. (The “stitched-together short stories” element is still present in the final manuscript, but not in a bad way.)

Whedon delights in the rhythms (or amusing lack thereof) of English as a spoken language; Black revels in undercutting expectations. What makes Wong different is his chosen medium: a prose novel. David’s monolog carries us through every page like we’re a surfer who has caught the perfect wave of metaphors and similes. At one point, David chronicles a battle against a monster that is “flinging chairs like Bobby Knight.”

(One other author comes to mind: Pop-culture wordsmith Chuck Klosterman. But he has branched into SF only once, in 2011’s “The Visible Man.”)

Things from another world

As for those monsters, another influence must be mentioned. Wong unapologetically uses Lovecraftian beasts from a parallel world. The descriptions are decent, as is the exploration of that parallel world in the later chapters of this beast of a book (469 pages, including a hilariously long 50-page epilog).

The multiverse theory is likewise not Wong’s, although he does get in on the ground floor of the popularity bell curve. This type of world-building – requiring a pseudo-scientific explanation of how worlds are linked – risks hampering the story flow, but that doesn’t quite happen. This is partly because Wong so evocatively writes David’s addiction to “soy sauce” – a drug that allows David and John to see the monsters.

The amusing nature of Wong’s prose always wins out over the scares. In one sequence of wry humor, John attacks a monster by repeatedly striking it in the crotch, only to learn it is a giant artificial prop.

Character creation

That’s not to say “JDATE” is one big joke. While the supporting cast is thinly written, Wong does create three distinct main characters. David is self-deprecating, but also deprecating of life itself. His struggles with self-confidence are relatable. Fascinatingly, this metaphorically manifests as a lack of “self,” period, as David suspects he might be a pod person rather than his original self.

He doesn’t let this craziness turn him into a bad person. In one strikingly non-comedic flashback that almost feels like it belongs in a different novel, David argues to Amy that he is a bad person. But even then we can see he was in the right in a fight against school bullies.

For John, life comes easily; David often finds him suddenly dating a girl David had a crush on but was scared to talk to. Still, his lot in life – working at the video store – is the same as his friend’s. John is more enthusiastic about monster-hunting, and that enthusiasm pushes our reluctant narrator along the same way Randal pushes Dante.

Pretty redhead Amy is perhaps defined too much by how David adores her, making her more object than subject. But the author does nice work in showing how Amy’s missing hand (the result of a car accident) has made her withdraw from society, and how the public school system didn’t merely do nothing to help her; it made things worse by mis-categorizing her as “retarded.”

A ‘retarded’ story, smartly told

“Retarded” is Wong’s favorite adjective. It was a politically incorrect word in 2001, 2009, and still today. But David’s wry, uncensored conversational style shows his comfort in telling the story to us. I like to think that if a reader doesn’t like that word, they’d like David enough to laugh off its usage.

The monsters and multiverses can be found elsewhere, done better (or at least more scientifically). This novel – which has been followed by three sequels — is a page-turner because of the words themselves rather than what they represent.

Although 469 pages is long for a humor-laced mashup of “Clerks,” “Freakylinks” and Lovecraft, I love the rhythms of David’s storytelling. Granted, I built in some reading breaks. But I never lost my appreciation for how Wong makes a cliched story as addictive as the book’s soy sauce.