I wouldn’t be capable of starting a successful religion; I don’t have the requisite charisma, ambition or ability to deceive. But I do have my own private religion, and I call it Carlinism, based on the idea that happiness is found by emotionally removing yourself from the human race and viewing it all as entertainment. Another tenet is that if you don’t vote, you preserve your right to complain; if you DO vote, you helped caused the problem, and you have no right to complain.

(Like any self-deceiving religious person, I’ll just skip over the parts of Carlinism I don’t quite agree with, like the belief that everyone should drop acid at least once in their life.)

But really, there’s no need for me to preach, because George Carlin was able to put together quite a congregation on his own.

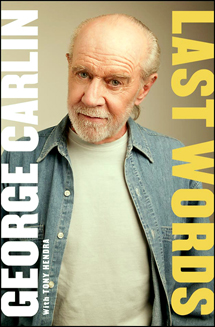

Carlin’s autobiography, “Last Words,” is a wonderful read. The comedian had been working on it for the last decade of his life, and after he died in 2008, his friend and fellow comedian Tony Hendra put the finishing touches on it and published it last November. Don’t worry, though, these are Carlin’s words.

Judging by the in-depth interviews Carlin gave in his later years, few entertainers talk about themselves with more honesty and detail than Carlin did, so I’m not surprised that the book is in this vein. Some of it is stuff you’ve heard before, but in the later chapters, we get deeper into Carlin’s brain than ever before.

Carlin saw the chapters of his life the same way a historian would; there are essentially three phases — 1) making it as a mainstream comedian in the ’60s; 2) becoming a counterculture icon in the ’70s; and 3) being the observant, articulate commentator on his HBO specials from the mid-’80s through his death.

It’s Carlin Phase 3 (what the comedian called the truest version of himself) that I like best, although in the first two phases we can see the true Carlin starting to emerge — for example, his “Seven Words You Can’t Say on Television” from his hippie era was the launching pad for many pieces about language and the politics thereof.

The real joy of “Last Words” is the insights Carlin gives into people (like a lot of us, Carlin hated people en masse, but he liked people as individuals). He talks about how his best friend/manager, Jerry Hamza, had the vision for Carlin’s HBO success way back at the beginning. Carlin writes that while he was open to change, it wasn’t in his nature to force change, so other people instigated each phase of his career. If not for Hamza, Carlin might very well have faded away into the realm of has-been comics. So I think I speak for all Carlin fans when I say “Thank you, Jerry Hamza.”

Carlin writes about briefly interacting with other comedians (in the “club” that he never felt a part of). He had a good, human exchange with Steve Martin, not so much with Billy Crystal or Martin Short or Lorne Michaels. That makes me feel connected to Carlin, because I also admire Martin, but feel a little cold about the others’ work. As for Dennis Miller — the closest thing we have to The Next Carlin, although his career has stalled at the moment — Carlin says he found him a bit arrogant, but he liked how his brain worked. That’s the same feeling I have about Miller; connections like these reinforce my devotion to Carlinism.

There is one paragraph in “Last Words” where Carlin does set aside his pragmatism and analysis: Writing about his second wife, Sally Wade, he unleashes a stream of clichés about love at first sight and all that (“The weird thing is, they’re all true,” he writes. “At my age, I’m allowed a little inconsistency”). It’s a touching paragraph.

The penultimate chapter is the book’s best: Carlin gives insight into what he was feeling as he performed in front of a crowd. He says his brain was split into two parts: One was focused on delivering the act effectively, the other was analyzing his act and the audience’s response. Carlin loved many specific individuals, but he was suspicious of groups (the larger, the scarier — national governments, for example). But he made an exception for his own audiences, because he could feel the connection with them. As he writes on page 281:

And there’s the need to find things out about them. To make kinships: “I feel this way about abortion, Volvos and farts.” “Yeah! Me too!” “You too? OKAY!”

In the last chapter, Carlin writes about his plan for the fourth phase of his career (although he had several heart attacks, he didn’t plan on dying at age 71): A one-man autobiographical Broadway show where he would perform all the characters. Acting was always important to Carlin, if not his fans so much (I haven’t even seen the mid-’90s curiosity “The George Carlin Show,” although I notice it is now available on thewb.com, so I plan to check it out).

His legacy is the way he pushed the art of stand-up comedy to a point where observation and criticism about the world we live in could be the bulk of the act. No one had really tried that before Carlin got rolling with those HBO specials. And few are doing Carlin’s brand of macro-observational comedy now, although Carlin certainly paved the way for more brilliant wordsmiths who are sensitive to humanity’s direction.

God knows, in 2010, we need The Next George Carlin.

Comments

![]() Really, everyone SHOULD drop acid at least once in their lives … not at a rave or a dance club, but in a park or some other peaceful, open setting, preferably with trusted friends. The world would be a much better place if people would peer beyond the veil and bit and see a little of the magic.# Posted By DaJuan Hayes | 10/25/13 6:03 AM

Really, everyone SHOULD drop acid at least once in their lives … not at a rave or a dance club, but in a park or some other peaceful, open setting, preferably with trusted friends. The world would be a much better place if people would peer beyond the veil and bit and see a little of the magic.# Posted By DaJuan Hayes | 10/25/13 6:03 AM

![]() Fair enough. While it’s not my cup of tea, I certainly don’t condemn anyone for trying it, just so long as they don’t hurt other people while doing so. And I think it’s safe to say George knew more about this subject than I do.# Posted By John Hansen | 10/25/13 5:24 PM

Fair enough. While it’s not my cup of tea, I certainly don’t condemn anyone for trying it, just so long as they don’t hurt other people while doing so. And I think it’s safe to say George knew more about this subject than I do.# Posted By John Hansen | 10/25/13 5:24 PM