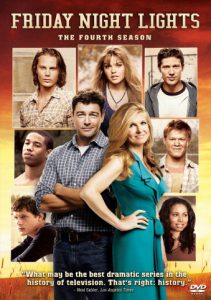

The NFL draft hype has finally passed, but we still can’t escape football, because “Friday Night Lights” (7 p.m. Central Fridays) has just started its fourth season on NBC (following its run on DirecTV, which I don’t have). Although I’m not a big fan of America’s new national pastime — I prefer the old one, baseball — this is one hour of football-themed TV that I can get behind.

And the Dillon Panthers used to be the fictional team I rooted for every week. But, in a twist that capped Season 3, Coach Taylor is now helming the East Dillon Lions, and the Panthers are the enemy. Entertainment Weekly’s review of the first episode says you’ll be amazed by how quickly you start rooting for the Lions and against the Panthers.

But it’s not so amazing. Most “FNL” fans root for Coach Taylor, and anyone who’s ever been laid off or wrongly fired by a company knows how quickly you can go from devoted, hard-working loyalty to disgust and hatred.

My main complaint about “FNL” through the years is how the writers sometimes create artificial drama out of a high school football season, something that should be inherently dramatic. The most ridiculous plot was in Season 1, when the Panthers had to build a football field in a week. But you could also point to any of the lightly detailed (and allegedly thrilling) second-half comebacks by Taylor’s teams.

Nonetheless, “FNL” has always been a top 10 show for me. That’s because while the broad strokes are silly, the details are so well done. Season 4’s ridiculous conceit is that the town of Dillon has been redistricted into two high schools and — thanks to the manipulations of the boosters who got Taylor booted — Dillon has all the good players, coaches, teachers, facilities and equipment, and East Dillon has the dregs (plus Coach Taylor, of course).

But the off-field details make it work. Tammy Taylor, still the principal at Dillon (It’d be fun to say “Take this job and shove it” and transfer to East Dillon, but her family needs the money), claims in a community meeting that the two schools are equal. But when daughter Julie announces she is transferring to East Dillon, Tami is speechless. She finally musters a strangled “No!” but no doubt recognizes her hypocrisy.

The only thing rattier than the field and the locker room — leftover from the last time Dillon was split into two schools (a very silly convenience, because school buildings don’t generally sit empty waiting to be turned into schools again) — are the players. Landry is the only one we know from the old Panthers. As the now-graduated Matt Saracen tells him, he was a scrub for the Panthers, but he can start for the Lions.

The new quarterback, who comes to East Dillon as part of a second-chance program for young criminals, is the guy we’ll want to root for as the season goes on. Because Coach Taylor has taken these bad-news Lions under his wing, we as viewers want to do the same.

I suppose Season 4 is building toward a finale showdown between the two schools. (It’s a good finale to aim for, because they’ve already done the state championship win, the season without an ending, and the hard-fought state championship loss. It’s good to mix it up.)

But that’s for the future. In the first episode, we cut between the two season-opening games: Dillon on its glitzy field with full stands; East Dillon on a poorly lit scrub of grass with a smattering of supporters. We follow the Lions to the bitter end: Taylor has to forfeit at halftime for the sake of his players’ safety (the QB has a high ankle sprain, the lovable lineman can’t feel his arms and Landry is spitting out blood).

But then the episode ends; we don’t see the conclusion of the Panthers game. I didn’t mind at all, and of course, I wasn’t supposed to. For now, the talent-rich Panthers are a much better team, but pathetic East Dillon — which is only learning how to play as a team — has my heart.

Go Lions, and go “Friday Night Lights.”