Following journeys to a theme park in the desert, the barren wilderness of Alaska, a computerized skyscraper and the bottom of the ocean, Lincoln Child explores yet another fascinating corner of the Earth — and his own imagination — in “The Third Gate” (June, hardcover).

I had always considered Douglas Preston, Child’s writing partner on the Pendergast books, to be the superior solo writer, but Child comes up to his level with this horror/adventure/mystery yarn about of ancient Egyptian curses, near-death experiences and, most evocatively, the Sudd, a stretch of the Nile River that’s essentially an impassably thick swamp.

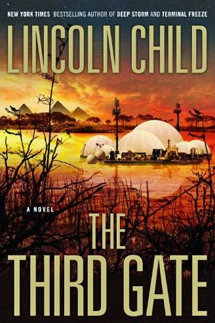

It’s always a slight disappointment to read the author’s note and the end of the book and find out what part of the story was based on fact, and what was fiction. For the record, the Sudd is real, but Child brings it back to a more primal time before politically driven wars had ravaged Sudan. Basically, the expedition is able to pay off the authorities and have this corner of the planet to themselves to dig up the past. As in most of Child’s stories, we get a neat mix of modern, computer-driven civilization (in the form of the floating research station shown on the book cover) combined with mysterious and dangerous Mother Nature.

Main character Jeremy Logan is serviceable (as with another great sci-fi imaginer, Michael Crichton, Child is a bit stronger on story and theme than character), and his interactions with other characters carry us through the yarn — old pal Ethan Rush, a near-death experience expert; Ethan’s wife Jennifer, who had an NDE herself; Tina, the group’s Egyptologist; and Stone, the eccentric founder of the mission. For his part, Logan is the expert on curses.

Logan is also the audience surrogate (and usually he’s the one we follow, but there are a few exceptions; in fact, the book opens with Ethan Rush), because he’s brought into the mission late and surprised at every turn as Ethan brings him to Rhode Island, London, Cairo, and finally the Sudd. Likewise, the plot thickens incrementally, as does a readers’ knowledge of ancient Egyptian culture. As I often do with Child books, I just cracked open “The Third Gate” without knowing any more than the title, then realized, “Oh, so this one’s about Egyptian history.” Child, along with Preston in his solo work, never fails to pick up a topic that I’m at least sort of interested in, and without fail my interest grows as the book continues.

In the final act, there are a few conveniences, and one could argue that some set-ups don’t pay off as well as they could’ve — there are an awful lot of big ideas crammed into this story. Still, Child’s imagination in “The Third Gate” got my own imagination going, perhaps on tangents that the author himself didn’t foresee. I polished off this book in a few days and it stayed in the forefront of my mind the whole time; I found myself looking forward to getting home from work so I could knock off a few more deliciously evocative chapters.