This is part of a series where I will look back at various works of “Batman” lore from the perspective of a casual “Batman” fan who enjoys the current TV series, “Gotham.”

Something I should understand as I embark in my “Batman” journey is that I can’t be attached to continuity if I’m going to enjoy it. This is hard for me as a “Star Wars” Expanded Universe fan. “The Dark Knight Returns” (1986) is set in the year of its publication (elements such as Reagan being president and a cold war with Russia attest to this); 10 years after Batman’s retirement is sparked by the death of the second Robin, Jason Todd; when Bruce is 55 years old; and when Commissioner Gordon is about to retire.

But writer Frank Miller – whose work I know from the deliciously stylish “Sin City” movies, which are live-action adaptations of his comics – wasn’t following the comic continuity of the time: Batman hadn’t been gone from the drugstore racks for a decade when he wrote this; he didn’t retire in 1976. Nor was Jason Todd dead, although the mainstream “Batman” comics did kill him off later.

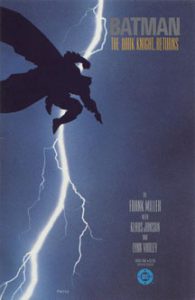

“Batman: The Dark Knight Returns” (1986)

DC, four issues

Writer: Frank Miller

Artists: Frank Miller (pencils), Klaus Janson (inks), Lynn Varley (colors)

The simple answer is that Miller created a new timeline for the sake of telling this story. The more complex answer – as a cursory web search tells me — is that “Dark Knight Returns” is set in the New Earth multiverse, in the branch called Earth-31.

It gets more confusing: There are “Dark Knight Returns” prequels set in the 21st century. This is possible because of the comic-book storytelling device of a floating timeline (a.k.a. sliding timescale), which my friend Steve told me about. Under this device, if you’re reading a modern-day prequel, you have to imagine it leads into a “Dark Knight Returns” that is set in the future, even though the story (as it is published) takes place in the 1980s.

Only four issues, but it reads like a novel

While the fact that “Returns” exists in a vacuum of continuity leads to some problems (which I’ll address later), I’m going to stop thinking too hard about that right now and instead focus on the story. When I asked my colleague Lisa, a longtime casual “Batman” fan who doesn’t keep track of the specific multiverses, about the place in the lore of her favorite “Batman” comic series, “Legends of the Dark Knight,” she simply said “They were just good stories.” That’s the only perspective from which to analyze the “Batman” franchise without being driven mad by continuity issues.

“The Dark Knight Returns’ ” most striking aspect is that while it consists of four issues, it reads like a novel — it took me about six sittings to get through it. (And “Returns’ ” movie adaptation from 2012-13 is the only DC animated adaptation that’s split into two parts.)

Every page is dense. But it flows beautifully, as Miller intersperses TV news blowhards talking about the issues with the actual events in Gotham: The rise of the criminal Mutants, the reactionary rise of the crime-fighting Sons of Batman, Batman himself mulling a return to action, and 13-year-old girl Carrie Kelley deciding to become the new Robin.

This Gotham feels familiar right off the bat (no pun intended), as newscasters note: “It’s 97, with no relief in sight. … This heat wave has sparked many acts of civil violence here in Gotham City.” Off the top of my head, “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” and “Predator 2” – both from 1990 – started with a big-city heat/crime wave.

In the fourth book, nuclear winter descends; again, I’m reminded of “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,” but in this case the opening arc of the Eastman/Laird comics, when the Turtles retreat to Massachusetts in a snowy winter. Those issues came out soon after “Dark Knight Returns.” This story is too layered to be ripped off, but there’s an ambiance to it that might have seeped into the psyches of other comic-book and action-film storytellers.

Themes aren’t at all dated

The biggest accomplishment of Miller’s work is that it hasn’t aged a bit in 31 years. In a story that includes Eighties elements like Reagan, nuclear warfare, Letterman, neon arcades and punk fashions (the Mutants wear visors, and the SOBs have colorful Batman symbols tattooed on their faces), this theme is timeless: The blurring of the line between the good guys and the bad guys.

In the 2010s, we hear about legal crimes committed by supposed “bad guys” (whistleblower Edward Snowden) and moral crimes committed by supposed “good guys” (the cops who killed Eric Garner for selling untaxed cigarettes). I don’t know if Miller was going for a snapshot of 1986 or for timelessness, but “Returns” is not thematically dated at all.

While not many stories are set in the “Dark Knight Returns” timeline, its influence on other “Batman” works is substantial. Miller introduced the dark, psychologically troubled version of Batman, and the scary, crime-ridden Gotham. It seeped into the Burtonverse movies and “The Animated Series” of the 1990s and — more overtly – the “Dark Knight” film trilogy of the 2000s and this decade’s “Gotham.” This contrasted with previous versions, including the most mainstream take, which was 180 degrees removed from Miller’s: The Caped Crusader from the 1960s TV show.

To cite more specific influences: The massive-wheeled Batcycle and tank-like Batmobile pop up in the “Dark Knight” film trilogy. Jared Leto’s Joker in “Suicide Squad,” with an emphasis on the green hair and white face and less wild stylization than other interpretations, looks a lot like this Joker, as drawn by Miller, Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley. An armored Batsuit appears in “Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice,” which also takes up the concept of a middle-aged Batman and his fight with Superman – although the thing they are fighting about is different. And the closing “funeral” here is Batman’s; in that movie, it’s Superman’s.

Carrie Kelley takes over the Robin role

The character who surprised me the most – and who is my favorite character here – is Carrie Kelley, a teenage Gothamite with neglectful parents and (unfortunately unexplained) acrobatic skills who buys a costume, sneaks out of her apartment window, climbs down a drain pipe and becomes the new Robin. (There are rumors that Carrie Kelley will be the Robin in the DC film universe, perhaps played by Jena Malone, which would make her older than this version.)

It feels right that if Robin is not one person, but rather a series of people taking up that name while serving as Batman’s sidekick, that one of them can be a girl. Robin’s name and costume are both unisex. And it was somewhat of a novelty in early 1986 – Ripley didn’t mow down xenomorphs in “Aliens” until later that year — to have a female action hero outside of nonhuman superheroes like Wonder Woman and Supergirl. Yes, there was Batgirl, but only in the safer, pre-Dark Knight version of “Batman.”

Kelley’s presence in the story is essential because she brings a dash of youthful exuberance (she often views Batman’s exploits with wide-eyed or grinning amazement) to an otherwise relentlessly grim story. While “Returns” has satire (for example, Reagan saying “We must protect our interests – I mean! Fight for freedom!”), it’s a resigned, cynical form of satire. But it ALMOST becomes worthy of a smile when Batman tells Robin she’s “fired” if she doesn’t follow his instructions, and I’ll grasp any sliver of light in this story.

Because “Returns” is not continued from a specific existing narrative, that gives it a bit of a cold feeling at times. We get the general sense of Batman’s past rivalries with Two-Face and the Joker, and Green Arrow’s late-in-the-game appearance mostly works.

Like Batman, he has retired from professional superhero-dom in order to avoid the wrath of the Reagan establishment that has turned on superheroes who don’t toe the line. We don’t know why he’s missing an arm, but we can grasp his bitterness and understand why he joins Batman in the fight against Supes. That having been said, the fact that the backstories are merely sketches creates an emotional hole when we see Two-Face, the Joker and Green Arrow.

Aging Batman sets an example

The latter fallen icon – who, like Batman, is a superhero with no superpowers – is one of many people who are inspired by Batman to do the right thing in “Returns” because he sets the example, and has a history of doing so. Gordon understands this; the new anti-Batman commissioner, Yindel, does not: “Maybe you’ll understand someday,” Gordon says as he hands off the reins.

Through Gordon’s words, Miller is noting that the DC Universe has a Batman, but the real world does not, and we’re worse off for it. Ironically, we’re also worse off for our insatiable desire to find a Batman. Everyone who ascends to widespread respect also seems to have a dark side; Miller specifically picks on the beloved Reagan as the embodiment of imperialism, which makes sense for a 1986-penned work, but all U.S. presidents since then could effortlessly hold this role.

Politicians are probably the worst cohort to look to for heroes (celebrities are also pretty bad options), but the populace struggles to lionize an extraordinary common person. Maybe no one is equipped to fill the Batman-sized hole in the real world – the amount of machine-gun fire he dodges in “Returns” is, after all, pure wish-fulfillment. Any prospective “real” Batman died in training before we even knew him.

And besides, there remains the question: How does Batman hit that sweet spot where he is accepted as a leader without any official authority backing him? Indeed, the authorities from the city level to the national level aggressively oppose him. Imperialist America and its henchman, Superman, are the villains here; that alone made this comic daring for its time. But it’s nice that we can somewhat see Superman’s perspective.

Bats and Supes clash

I’m not crazy about either Batman-Superman conflict, but the one in “Dark Knight Returns” makes more sense than the one in “Dawn of Justice,” where Batman attacks Superman based on a sketchy vision of a possible future. In “Returns,” Superman’s taken-too-far nationalism is worthy of pity, because he started from a noble position.

On Reagan’s implied orders (“Do what you have to do”), Superman decides to take out Batman because the public has turned against the Dark Knight, and Supes feels serving the public’s wants is the best long-term strategy. I don’t agree with that, but at least Superman has thought about this long and hard; he isn’t merely reacting, as Batman does in “Dawn of Justice.”

Batman stands against all the things that Superman and imperialist America stand for, and that are parodied throughout the book, particularly the notion that listening to politicians and TV pundits allows us to accurately label a person, or accurately define an issue.

But what Batman stands FOR is murkier. Batman isn’t an authoritarian, but he’s also not an anarchist. He doesn’t particularly care about individual liberty, so he doesn’t fit the mold of a libertarian hero the way his contemporary V from Alan Moore’s “V for Vendetta” (1987-88) does. As he sarcastically says to one of his criminal targets during a shakedown: “Yeah, you’ve got rights. Lots of ’em.” Often in “Returns,” I don’t like Batman, even though I always like him more than Superman, Two-Face, the Joker and the various street criminals who try to gun him down.

It might be as straightforward as common decency and always doing the right thing. On Batman’s word, the Mutants, the Sons of Batman, the citizen looters and the public officials – every cohort of which is at least some degree of villainous — all get together to become heroes and put out the fires in the heart of Gotham caused by a plane crash.

Timeless societal struggles

This is Pollyanna-ish for such a grim story, but the point is that Batman has the power to make this happen by being Batman. Superman, a more obvious candidate to be an inspirational figure (indeed, Reagan calls him “the next best thing” to God), does not, because he has chosen to serve as a cog in the machine.

So I side with Batman. Still, I feel somewhat chastened by story’s end for rooting for anyone in “The Dark Knight Returns” – which I suspect is the point.

Not just important for learning the historical roots of the Dark Knight version of Batman, Miller’s classic holds up as a layered read that illuminates both the 1980s and timeless societal struggles. It’s not the “Batman” universe I’d like to spend most of my time in (at this point in my explorations, I’m partial to “The Animated Series,” “Gotham” and some entries in “Legends of the Dark Knight”), but I can appreciate why it gets referenced so often as a piece that influenced both “Batman” and the wider comics industry.