Welcome to a new series where I look back at the books and movies of the “Psycho” franchise before its revival in “Bates Motel,” one of the best TV shows of the decade, which will conclude its five-season run this month.

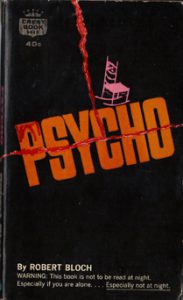

Let’s start at the beginning with Robert Bloch’s novel “Psycho” (1959). At 125 pages, it can be breezed through in a few sittings. Although it was popular enough to come to the attention of Alfred Hitchcock, whose movie adaptation came out a mere year later, it apparently wasn’t so popular that it spoiled the famous twists.

Bloch’s “Psycho” is a character study of Norman Bates; a dime-store novel crash course in psychopathy, split personalities and transvestites; and also much more of a mystery than the film or TV incarnations. Since it’s not a visual medium, a 1959 reader would naturally assume that Norman is truly talking to Mother (not named Norma until late in the book). Then when it’s revealed in the final pages that she is a taxidermied corpse, a reader would go back and see subtle hints. I bet Bloch fooled most readers.

Bates is superficially different from later portrayals – he’s 40 and fat, and he drinks hard liquor when he gets upset. He is also his own psychologist in a way: Being a voracious reader (he loves to escape into the world of books, including those about personality disorders), he has a good grasp of how his overbearing Mother has warped him. Or rather, one of his three identities has a good grasp of that. As a psychologist reveals in the epilogue, he is split into Norman, Norma and “Normal.” In a portrayal also seen in “Bates Motel,” the third one is aware enough of the other two personalities to act normal in front of other people.

Norman Bates comes from Bloch’s imagination, but the author does throw in a reference to “the (Ed) Gein affair up north” (p. 118), perhaps anticipating that critics would make the comparison. (One of the things I’m looking forward to in “Bates Motel” is seeing if Chick, who has been taking notes on Norman’s behavior, writes a novel called “Psycho.”)

Hitchcock’s famous trick of having Marion Crane (Mary Crane in the book) seem like the main character until she’s killed at the end of the first act isn’t found in the book. The first chapter starts with Norman. Ultimately, Norman shares main-character status with two interested parties who are looking for Mary: Her sister, Lila, and her boyfriend, Sam Loomis.

As in all incarnations, Mary steals the money ($40,000 in hundred- and thousand-dollar bills here) from her boss on a crazy whim and drives many hours to meet her boyfriend. In the film, Sam is hesitant to move on after his separation; in the TV show, he’s an outright womanizer. In Bloch’s telling, like a hero from one of Philip K. Dick’s non-sci-fi novels of the era, Sam is an unabashed good guy who runs a hardware store, determined to pay off the debt racked up by his dad and run an above-board business. He accidentally kisses Lila when he first sees her – mistaking her for Mary – but everything’s chaste after that. Somewhat helped by a private investigator and the Fairvale sheriff, Sam and Lila are ultimately the main investigators of Bates, because they have the personal stake of looking for Mary.

Considering the iconography of the Bates Motel and the house on the hill above it, it’s interesting to note a couple things. First, the layout of the grounds: Bloch has a road running between the two buildings, then curving behind the house. A swamp at the back of the property is where Norman dumps the bodies and cars (The lake is farther down the highway in the TV show). And the house seems to be on a slight rise, not towering above the motel. Bloch colloquially uses the term “up” for all directions (Norman goes “up” to the house, but also “up” to the motel). But the film’s portrayal obviously won the day, as the house-and-motel image is featured on the cover of the 1993 “Three Complete Novels” collection; unavoidably, this is what I saw in my mind’s eye.

The inside of the house seems familiar, though, as Bloch illustrates that the décor hasn’t been updated in a half-century. As such, it has turn-of-the-20th-century stylings. The P.I. notes that there’s not even a TV in the house, placing Bloch’s book amid the affordable-TV boom. This concept was continued (but moved forward in time) in “Bates Motel,” with the house looking like it’s stuck in the mid-20th century; Norma gets a flatscreen TV at one point, irritating Norman.

The second oddity about the Bates property: It’s bizarre that this iconic location isn’t definitively set in a certain place. From context clues, I place the book’s Fairvale in south-central Kansas, but “Kansas” doesn’t appear anywhere in the text. I had thought it was in Oklahoma through most of my read, until Bloch makes reference to Oklahoma being south of Fairvale. Hitchcock moved the house and motel to California, and the TV show moved it to Oregon and renamed the town White Pine Bay. Mary/Marion drives up from Texas in the book, up from Arizona in the film and down from Seattle in the TV show.

The book’s epilogue is a bit odd, as Sam breathlessly recounts to Lila what he learned from the psychologist. Becoming Bloch’s surrogate, Sam’s fascination with Norman’s addled mind has trumped the fact that his girlfriend was killed in horrific fashion. After hearing the tale, Lila notes: “And right now, I can’t even hate Bates for what he did.” That rings a bit false to me.

Still, it’s understandable that this was a fascinating read in 1959, as many of the concepts were fresh. (On page 120, Sam asks Lila, “You know what a transvestite is, don’t you?” That’s a line that wouldn’t appear in a modern book for multiple reasons.) It’s structurally savvy, too, as Bloch will reveal something, such as the investigator’s POV of his conversation with Bates, then take a step back in the next chapter, where we get Norman’s perspective of the conversation. This staggered momentum creates tension.

Additionally, he parses out information on Bates lushly but sparingly, leading to the final clincher where he totally embraces the Mother persona — just as Norman believes Mother is the murderer, Mother believes Norman is.

Fans of “Bates Motel” might be curious what Bloch devised for Norman’s formative years. In the book, Norman lethally poisons his mom and her lover, Joe Consadine, 20 years in the past. (In the book, Joe and Norma built the motel, rather than purchasing it, as per “Bates.”) In the TV show, he gasses Norma and her husband, Sheriff Romero. In “Bates Motel,” Norman is responsible for several murders, starting with that of his father, who is barely mentioned in the book as a man who split up with Norma long ago.

In Bloch’s novel, a reader might assume that Mary is Norman’s first victim since his mom and Joe Consadine. However, it’s not explicitly stated, and the author leaves the door open for more wrongdoings in the past. On page 118, the media “tried their damnedest to make out that Norman Bates had been murdering motel visitors for years. They called for a complete investigation of every missing person case in the entire area for the past two decades, and urged the entire swamp be drained to see if it would yield more bodies. But then, of course, the newspaper writers didn’t have to foot the bill for such a project.”

Just as Bloch’s “newspaper writers” were fascinated by Bates’ backstory, so were TV writers a half-century later, leading to “Bates Motel.”