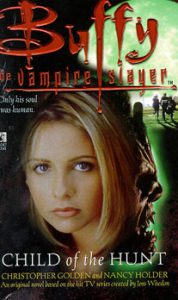

Like all successful SF/fantasy franchises, “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” quickly inspired spinoff novels. The first handful were in the young-adult genre, but when it became apparent that the show appealed to not only high schoolers but to anyone who had ever been in high school, a new series of “adult” novels was commissioned. The first, from Christopher Golden and Nancy Holder, was “Child of the Hunt” (October 1998), which came out as the third season began and is also set during that season.

I remember delightedly spotting this buried in the sci-fi section at a Barnes and Noble (as there was no distinct “Buffy” section yet), having not realized that “Buffy” had branched beyond TV. (“Buffy” to read during the interminable week between eps – yes, please.) I remembered it being a strong book, and it mostly holds up on a re-read today. Golden and Holder know the Scoobies’ voices, and while they edge toward having too many quips and pop-culture references, they’re at least more toned down than the current “Buffy” comics.

I’m guessing the key distinguishing features between the YA and adult lines are more emphasis on relationships and a deeper mythology to the villains. The TV series’ lack of interest in the Scooby Gang’s (or Slayerettes’, as is the term at this point) parents – other than Joyce, of course – is arguably a feature rather than a bug, something that can inspire essays about the gulf between generations.

However, “Child of the Hunt” is very interested in the kids’ relationships with their parents. The Joyce-Buffy relationship is somewhat icy, as Buffy has recently returned to Sunnydale after having run away. Joyce is leading a community initiative to combat the runaway problem; Season 3 would later tread similar ground with “Gingerbread” (episode 11).

Additionally, we get scenes with the Rosenbergs – Willow’s dad is identified as Ira, because she mentioned his name in Season 2, whereas her mom is merely Mrs. Rosenberg, as she won’t be named Sheila until “Gingerbread.” They are concerned about their daughter, as are Cordelia’s folks.

Xander is envious of this, wishing his parents would care enough to ground him, although a case could be made that they are more distracted than uncaring – they don’t seem quite as awful as in Season 5’s “Hell’s Bells.” In an interesting continuity point on page 295, we learn that Xander has an older brother, during an inner monologue from Mrs. Harris: “She frequently wondered why she just couldn’t seem to shed the twenty extra pounds she’d gained when her oldest had finally moved out on his own.” That’s probably a continuity error by the authors, as I believe Xander (like all of the Scoobies except Tara, unless we count Dawn’s later appearance) is canonically an only child.

Overall, though, Golden and Holder do more mythology-building than toe-stepping-on. A prime example is Lucy Hanover, a 19th century Slayer who is the first Slayer mentioned in the “Buffy” canon, in the introduction to the series premiere. Although she’s not an active participant in this narrative, we learn that Lucy was a love interest of “Child of the Hunt’s” villain, the Erl King. In future Golden/Holder writings, we’ll learn more about her, and it should hold up, as the TV show doesn’t explore this past Slayer beyond that introductory nod.

A strength (and a safe zone) here is the writing of original characters, but this actually leads to good writing of the main characters. We meet a couple of homeless teens and a police officer, Jamie, who is torn up by his son’s disappearance. This allows for some good material for Giles, who befriends his neighbor Jamie. The way they bond over their losses (Giles having recently lost Jenny) almost makes up for Giles’ out-of-character suggestion to Buffy that she relies too much on Xander and Willow. To his credit, he never brings it up again after Buffy angrily shoots him down. I also like how Buffy respects Giles’ ability to distinguish Angel from Angelus; Giles isn’t buddy-buddy with the vampire, but he is accepting of him.

Cordelia, assigned to Jamie’s suicide watch, complains about it on the inside, but does it anyway, a nice display of her unsung heroism that would become more sung on “Angel.” The authors also anticipate the future of Oz’s arc, as the werewolf is able to somewhat control his morphing while in the magic sphere of the Wild Hunt.

Buffy’s desire to help Roland, a young man who is abused by a traveling Renaissance Faire, parallels nicely with how she helps the runaway girl in “Anne” (season 3, episode 1). And the writers somewhat copy (or anticipate, depending on when they wrote the lines) that episode, as Buffy breaks from her thrall and says “I’m the Slayer. I’m not like other girls” (p. 317), mirroring “I’m Buffy, the vampire slayer. And you are?”

The most distinguishing feature of the novels is that they introduce complex mythology-based backgrounds for their villains, whereas the TV series uses monsters as metaphors for Buffy’s life struggles. If you view this as a shortcoming of the show, you’ll love the books. I don’t view it as a shortcoming, but still, I do think a deeper dive into mythological monsters — taken in part from real-world mythology, I’m guessing — adds an intriguingly unique element to the books.

Mostly because of the amount of pages spent building the Wild Hunt into a deadly foe, there’s no denying that “Child of the Hunt” feels different from the TV show. Even though everyone is in-character, the stakes are so high here – Buffy is in serious danger of being in the thrall of the Wild Hunt for eternity – that it’s impossible that they wouldn’t mention it in the next week’s episode. I mean, Xander and Willow are hospitalized, for crying out loud.

What’s more, “Child of the Hunt” just barely squeezes into the “Buffy” timeline. The novel has to take place after “Revelations” (episode 7), because everyone knows Angel is back. From another angle, it ideally takes place before “Homecoming” (5) because the Xander-Cordelia and Willow-Oz relationships are in good shape, no “clothes fluke” having yet caused attraction between Willow and Xander. But in order to account for the gang’s knowledge of Angel’s return, it needs to be pushed forward to right before “Lovers Walk” (8), when Oz and Cordy discover Willow and Xander kissing.

I like to err on the side that the books and comics are canonical except in cases where they blatantly can’t be. “Child of the Hunt” can be, just barely. I am sympathetic to the fact that Golden and Holder had a fine line to walk, trying for high stakes that affect the characters without contradicting future revelations that they could only guess at. The novel’s canonicity is shaky, but its quality is on solid footing.

Click here for an index of all of John’s “Buffy” and “Angel” reviews.