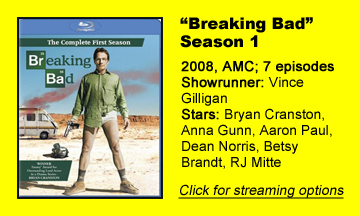

Over six Sundays, we’re looking back at the five seasons (and one movie) of one of the last decade’s elite TV series: AMC’s “Breaking Bad.” First up is Season 1 (2008):

A modest start

“Breaking Bad” is now considered one of the best TV series ever – it ranks No. 4 among TV shows on IMDB with a 9.5 rating – but it gets off to a modest start with the seven-episode Season 1.

Creator Vince Gilligan tapped character actor Bryan Cranston, from his 1998 “X-Files” episode “Drive,” to play Walter White, a high school science teacher who cooks crystal meth out of financial desperation. “Drive” isn’t one of my favorite episodes, but it shows Cranston’s skills and is “Breaking Bad” in a nutshell – his character, who has a bomb in his head, has to keep driving or die.

“Breaking Bad’s” premise is rather simple for an ultimately layered series: It takes situations we’ve seen in every crime drama but digs deeper into the human toll.

For example, Walter doesn’t have it in him to kill Krazy-8 (Max Arciniega), a drug distributor who he has locked to a post but who could rat out Walter and/or kill his family if set free. They get to talking, and we and Walter see Krazy-8 has some good traits. That’s how almost everyone is if you get to know them. Walter’s dilemma might be a cliché, but the moral weight is rare.

Violence is part and parcel to “Breaking Bad,” since it’s about the black-market drug trade, and I wouldn’t recommend this show to everyone. I generally shy away from violent entertainment myself.

Easy to watch despite violence

Yet I found Season 1 easy to watch even though it includes stunning violence and one of the grossest body-dispatching scenes ever devised. Walter’s partner Jesse (Aaron Paul, “Westworld”) douses a corpse in hydrochloric acid that burns through a bathtub, leaving bloody sludge on multiple floors of his house.

And when Tuco (Raymond Cruz), the meth distributor for a large chunk of Albuquerque, beats his own henchman to death (or near it; it’s unclear), it’s a stark illustration of how violence is inevitable without the structure of a legal market. Tuco uses violence to solidify his local monopoly, and no one can press charges because they are likewise criminals.

Season 1 is filled with “nope” moments like the body-melting and Tuco’s rage beating, yet we always understand why Walter chooses this line of work. The writers spell out the economics of the drug trade for the layperson without talking down to us. Walter and Jesse can make tens of thousands of dollars from a pound of meth.

With Walter’s down payment on his lung cancer treatment being $90,000 – not to mention the prospect of leaving his wife (Anna Gunn as Skyler), son (R.J. Mitte as Walter Jr.) and future daughter in debt – it’s logical and practical that Walter would take advantage of his scientific knowledge that hasn’t so far earned him big bucks.

(Despite what we hear about the Whites’ financial woes, they do live in a nice house. But maybe Albuquerque has a low cost of living. Or maybe this is the usual TV portrayal of being “poor.”)

Supporting cast has layers

While Cranston is the star, the supporting cast has layers, too. Mitte, who has a lesser form of the cerebral palsy displayed by Walter Jr., is endearing as a moody teen who nonetheless shows love for his parents. Dean Norris was born to play obtuse DEA agent Hank, who also happens to be Walter’s brother-in-law. (Skyler is the sister of Betsy Brandt’s Marie, Hank’s wife.)

“Breaking Bad’s” sentiment about the drug war avoids controversy early in its grand narrative. Hank (not knowing about Walter’s side business) tells Walter it’s a good thing that meth is now illegal, as it used to be sold in drug stores. I’m not sure if the writers intend this to be an ironic statement illustrating Hank’s conflation of illegality with societal safety. Likewise when Hank lectures Walter Jr. about how pot is a “gateway drug.”

Even if the writers are poking fun at drug warriors’ simple-mindedness, they also illustrate the physical toll of methamphetamine addiction. Hank shows nephew Walter Jr. a meth-addicted street hooker who is perhaps 30 but looks 60, and no one can argue with the cruel side effects of this drug. Jesse’s “friends” also display addiction traits, notably the aptly named Skinny Pete (Charles Baker).

Still, “Breaking Bad” has an undeniable tinge of dark comedy. It’s almost Philip K. Dickian when Walter is asked to list the stolen lab supplies at a parent-teacher meeting.

We know he stole them, but he has to put up a front. At other times, the show arguably goes too far, like when a real-estate open house is taking place upstairs in Jesse’s house while Walter cooks meth in the basement.

Avoiding confrontation

Tension is always present, but at the same time, “Breaking Bad” shows us the odd reality that a meth dealer’s encounter with law enforcement isn’t inevitable. In the pilot episode, Jesse happens to be gone when his partner – Emilio (John Koyama), later to be killed and melted by the acid – is nabbed in a sting. You’d think his own door would burst down at any minute.

Jesse is doubly paranoid because of the effects of the drugs he takes (doing meth is necessary for people in the trade, as it proves you can be trusted). As episodes pass without a bust, one could see how Jesse might think he’s some sort of superman.

“Breaking Bad” is plausible wish fulfillment for anyone who feels marginalized. Whenever Walter’s health, finances and pride take a blow, it’s cathartic when he hauls in “fat stacks” or uses his newfound badassery to stand up for himself.

(Or for the common folk. Faced with a jerk who steals his parking spot and talks crudely on a Bluetooth in a bank line, Walter merely sets the guy’s car on fire. I suspect in later seasons, he’d beat the crap out of the jerk, maybe outright kill him.)

Shortened by strike

Season 1 is shortened by the writers’ strike, so it’s not a complete arc. Wisely, it picks up the narrative in Season 2, so everything flows for a modern binge-watcher. The season has a few problems, though: With Emilio’s body being a huge plot point, it comes off as a plot hole that we don’t see how Walter gets rid of Krazy-8’s corpse.

And the show tries to have it both ways with Walter’s medical choice: He dramatically announces to his family that he chooses not to undergo treatment, and instead live out his last months without the side effects. A couple scenes later, he changes his mind. This could be a nasty cheat for a cancer-patient viewer who has chosen a dignified demise over a harrowing treatment.

The AV Club outlined how the writers’ strike forced “Breaking Bad” modify its pace, and its slow burn is now a staple of cable, premium and streaming shows, for better or worse. Season 1 itself doesn’t wallow too much, though. It’s a starter pack, laying out the gripping questions of how far Walter will go and what will happen when Hank finds out.

It doesn’t need a cliffhanger or twist to bring us back — although Tuco’s beating of his henchman is a nice thematic grace note. Gilligan and his team have already planted several hooks.