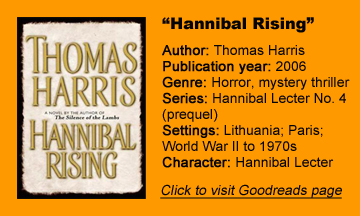

To mark the 40th anniversary of author Thomas Harris’ invention of Hannibal Lecter and the 30th anniversary of “The Silence of the Lambs” – the only horror film to win Best Picture – we’re looking back at the four books and five films of the Hannibal Lecter series over nine Frightening Fridays. Next up is the “Hannibal Rising” novel (2006):

(Way) back in time

I thought maybe “Hannibal Rising” would give us the story of Dr. Lecter’s early encounters with Will Graham, as referenced in “Red Dragon,” or his murders in the USA that earned him a spot in the Baltimore asylum. The fact that it does not – that it goes back further in time to tell his coming-of-age story – doesn’t in and of itself make Harris’ prequel a bad book. It perhaps just means there’s another book to come.

However, as time goes by, it seems less likely that book will happen. (Also, the TV series “Hannibal” has now done a deep dive into that territory. It’s a different timeline, sure, but Harris might feel like other writers have already chronicled this era of the doctor’s life.)

And as evidence that the author intends “Rising” as the only prequel, Paris inspector Popil describes Hannibal as a “monster” (chapter 53), an attempted link to “Red Dragon,” where Hannibal clearly has monstrous status.

As is Harris’ wont through this unusually but appealingly structured four-book series, a small mention from the previous book gets expanded upon: Here, it’s the reveal in “Hannibal” that Lecter had a sister, Mischa, who was murdered when she was 6 and he was 12.

In terms of horror storytelling, Harris milks this sequence amid a bitter Eastern European winter for all its worth as Hannibal somewhat reluctantly puts his memory back together in his internal “memory palace” for the sake of recalling the perpetrators.

Sympathy for the devil

Hannibal is 100 percent sympathetic throughout “Rising,” starting when he and his Lithuanian family become victims of Nazi depredations and continuing through his revenge quest against the people who killed and ate his sister. This desperate group of war-era nomads – who have “predator breath” and hide behind false Red Cross flags – are, by comparison, not sympathetic.

Harris’ writing is often evocative, although this novel has so many characters for its 368-page count that I was disconnected from the text more than in the previous three tomes.

The book’s strength is the way it shows the contagious twin evils of Nazism and Stalinism in World War II and its wake. People such as Popil are forced to decide between serving the invaders’ cause (and maybe making up for it later) or dying for what’s right (and therefore not committing any immediate wrongs).

Popil, who investigates young-adult Hannibal’s revenge murders, is a lesser evil in this book. But even the killers of Mischa make somewhat of a case for not being pure evil: They were dying and desperate. We can try to read all of this for pure entertainment, but it’s hard to not wonder what we would do in such dire situations.

Literary horror

Harris continues to come up with creative kills, and in the process we are impressed with Hannibal’s ability to trick and trap his enemies (although he also relies on luck here and there). Especially impressive is his creative use of a cadaver’s hand during a medical-wing pursuit.

Any sense that we’re reading puerile trash is undercut by those aforementioned deeper questions along with literary and cultural references, sometimes snippets of poetry or song in italicized foreign languages. (This is always the case in “Hannibal” books, but we can see the gears spinning here.)

Hannibal’s uncle Robert allows him space to paint, and after Robert’s death, his Japanese widow Lady Murasaki makes cultural and personal impressions on our impressionable title character.

“Rising” is a titillating, fun read at times, reminding me of “Buffy” tie-in fiction wherein vampires Angel, Darla, Spike and Drusilla take up the protagonist role; we root for them because the situations are so entertaining – even though in reality we would sympathize with their victims. Reader detachment and the fantasy element of vampires allow for the trick.

“Rising” isn’t all-out fun entertainment; the author paints the horrors of the Nazis and Communists too starkly for that. But at times I felt like I was just having fun reading about Hannibal doing his thing; cannibals are more real than vampires, but the dividing line isn’t thick.

Is Hannibal a monster yet?

On the other hand, Harris doesn’t convince me that Hannibal is a monster in these pages. That’s both a good and bad thing. In the abstract this is good because it suggests a layered portrayal when we can see positive traits in someone doing bad things. In actuality, it’s a flaw because Harris – through fairly unbiased observer Popil – states that Hannibal is a monster.

But is he?

I might have to do deeper reading about the relationship between morality and revenge to determine if Hannibal qualifies as immoral or amoral at this point, but it must be said that everyone he kills in “Rising” is a bad person – at least from what Harris shows us of them. They are part of the group that killed his sister or, in another case, a vile-tongued meat vendor who disrespects Lady Murasaki.

Hannibal does not kill anyone the world will miss, although one could make a case that he goes too far by killing them rather than turning them over to the authorities. Yet Harris labors to point out that authorities like Popil haven’t earned Lecter’s respect: The police were nowhere to be found when the Nazis killed his family, so why should they have a say in Hannibal’s pursuit of justice?

Harris totally achieves a portrayal of Hannibal as a victim who isn’t content to stay a victim, and who targets only his victimizers. I admire Lecter at the end of this book, if somewhat reluctantly because I have to overcome the mainstream notion that one should never take the law into one’s own hands.

Cathartic revenge

But I’m not sure that’s what the author aimed for, or if it is what he aimed for, if it should be the final statement in pre-“Red Dragon” storytelling.

While the fact that Mischa’s killers are partially victims of circumstance is raised in “Rising,” it’s more intellectual than deeply felt. Functionally, “Rising” is a cathartic revenge tale. When Hannibal heads off to Baltimore to start his psychiatric practice, I’m not at all sure he’s a monster just yet.

When next we meet Dr. Lecter, locked in a psychiatric ward cell in “Red Dragon,” he has killed many people, and he has maimed at least one innocent, a poor guard who gets her tongue and ear ripped out and her face shredded in a near escape. And he has injured Graham, who I think it’s safe to say did not have it coming.

If there’s another book to come, I might look upon “Rising” more favorably, but as it stands, it’s a step down from “Red Dragon,” “Silence of the Lambs” and “Hannibal” – all masterpieces in their own ways. “Hannibal Rising” is a decent read, but a comparatively generic one — a “Hannibal being Hannibal” romp that nonetheless doesn’t see this icon achieving “monster” status.