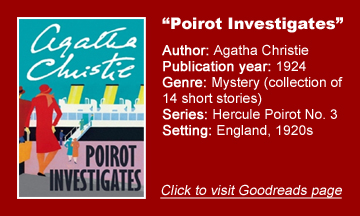

Early in my reading of the short-story collection “Poirot Investigates” (1924), I didn’t like how Agatha Christie was unleashing various tropes and tricks within such brief yarns. I felt like she should save them (especially her really good ideas) for her novels.

But a ways into this 14-story collection (the last three of which are only in the American edition), I started to look forward to each one as a mental snack. Not as fulfilling as the full-course meal of a Hercule Poirot novel (of which only two were published by this time), but tasty.

Tropes on display

Reading 14 stories in a row, it’s clear that Christie favors a handful of schemes for her criminals, such as faked identities, intercepted transportation of packets of bonds, and jewelry being stolen and replaced with “paste” versions (sometimes “stolen” by the owners for the sake of double-dipping on the value).

She often uses household-based murders wherein the servants are all potential suspects, and the layouts of rooms are important, so we get a sketch helpfully included by Hastings. And political intrigue comes up a surprising amount, notably in “The Kidnapped Prime Minister” (story No. 8).

Another commonality is that Hastings is on hand as Poirot’s narrator and punching bag, and the guy who shakes his head and chuckles over his friend’s arrogance in the latest example of “Poirot being Poirot.”

Hastings is like you or me trying to solve a mystery, whereas the genius Poirot uses his “little grey cells” to crisply solve every case — except the last one, “The Chocolate Box” (14).

At times, I had the sense that Poirot is successful because Christie writes him that way: In other words, there’s nothing intrinsic about Poirot’s method that makes it work; rather, he merely guesses correctly. Other times, the author achieves that perfect double play of a well-crafted mystery combined with impressive work by Poirot in navigating the facts available to him and the reader.

Middling mysteries

While “Poirot Investigates” is an enjoyable, brisk read, Christie fails to pen any truly memorable entries on par with her Poirot novel that followed soon after, “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.” The most memorable is “The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb” (6) because Poirot – much to his annoyance – has to travel to hot and dusty Egypt for the case.

I actually figured out a bit of his method for tricking and capturing the criminals: He makes the out-of-character statement that he believes in superstition, but of course he really means that he believes in the effect of superstition on people, and he uses that to his advantage.

Interestingly, Poirot doesn’t have to be on site to solve a mystery. In two cases, he solves it without leaving his office and quarters. In “The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge” (4), Poirot has the flu and solves the case from his bed, with Hastings sending him information in mailed letters. In “The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim” (9), Inspector Japp bets that Poirot can’t solve a case from his desk, and of course he does so.

I would’ve liked more out of “The Chocolate Box” just because it has the intriguing premise of a case Poirot failed to solve in his younger days working for a Belgian police force. It’s a relatively normal case wherein Poirot focuses on the wrong facts, but it does humanize him by showing he is imperfect and that he has learned from mistakes to become better at his job.

The entry before that, “The Lost Mine” (13), is the weakest, as Poirot’s recitation of a case to Hastings plays flat. Although Christie’s work always focuses on the crafting of a mystery and the intellectual exercise of solving it, it’s nice to have location atmosphere or colorful characters. That doesn’t happen in “The Lost Mine” and the other weaker entries.

Sign of the times

But in one of the best stories, we do get a peek into the times. “The Adventure of the Cheap Flat” (3), in addition to being a good puzzle, gives insight into the housing market of 1920s London, where the search for affordable lodgings is a dog-eat-dog game.

All told, I mostly enjoyed these 14 stories, but I prefer Christie’s novels at this point in my journey through her catalog. The short stories give us a good overall picture of Poirot, Hastings and the craft of mystery solving (and mystery writing, if you step outside the fictional world).

But by whittling the form down to basics, they also feel more repetitive and technical, and they often lack a bigger picture that rounds out a good novel.

Every week, Sleuthing Sunday reviews an Agatha Christie book or adaptation. Click here to visit our Agatha Christie Zone.