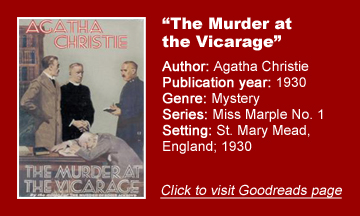

Agatha Christie couldn’t have known it at the time, but Miss Jane Marple would eventually become so iconic that a first-time reader in the distant future of 2021 might brace himself for an overhyped character. Providentially, Christie introduces the freelance spinster detective – who would become second only to Hercule Poirot in ubiquity among her sleuths – on the sly in “The Murder at the Vicarage” (1930).

Lightly humorous narration

The narrator is actually the vicar, Len Clement, who reminds me of the teacher from Jon Hassler’s 1977 novel “Staggerford” – a small-town community staple who sees everything through a wry and wary lens.

Enough of Clement’s inner comments are lightly humorous – like his observation that everything Marple says turns out to be right – that I imagine all his verbalizations are followed by a slight smirk. He’s an Everyman with flavor.

The vicarage is in St. Mary Mead, a small village — in which we focus on an even smaller area, with Christie providing one of those helpful maps. The best supporting character from the Poirot novel “The Mystery of the Blue Train,” Katherine Grey, also is from St. Mary Mead, but no connections come up here.

So the village is not small enough that everyone knows everyone else – but this particular area of the village happens to be quite gossipy.

Observant Marple

Although St. Mary Mead hasn’t experienced the excitement of a murder in at least 15 years, Marple has solved lesser crimes (in the magazine-published short stories, later collected in “The Thirteen Problems,” that precede her novel debut), and she reasons that solving a murder involves the same principles.

She observes people and their behavior from her garden – which has a footpath running past it – and knows how to set aside lies and false clues.

Smartly, Christie limits the number of scenes featuring Marple, although of course I was always aware that Marple would end up solving the case, rather than tightly wound Inspector Slack or our narrator, who functions as an armchair sleuth too. I might’ve figured this even without the character’s historic weight, because Clement refers to Marple’s keen eye enough times.

Colorful cast

But she is one of many colorful small-town characters, among them bachelor Lawrence, who has the attention of all the young women (who usually marry middle-aged guys, as is the case with Griselda marrying our narrator). One of those young women, named Lettice (and probably not pronounced “lettuce,” as I was doing for a while), has the interest of Clement’s heartsick nephew Dennis.

We get an amusing running thread about the Clements’ maid Mary, who is terrible at cooking and cleaning. But that makes her more appealing to Griselda, who tells her husband that Mary is less likely to leave for another job — and therefore they are saved the annoyance of finding a new maid.

As the various detectives gather information, Christie makes good use of the observations of domestic workers around town, including a nervous kitchen maid who is “more like a shivering rabbit than anything human.”

Humor nothing to sneeze at

“Vicarage” is perhaps Christie’s funniest book up to this point. It’s especially hilarious when an interview leads to Mary’s mention that she heard a sneeze around the time of the murder. The author makes great comedic hay out of “sneeze” being a funnier word the more times you read it. Our wry narrator reflects on the case in chapter 25:

“Nothing about a crime is ever ordinary. The shot was not an ordinary kind of shot. The sneeze was not a usual kind of sneeze. It was, I presume, a special murderer’s sneeze.”

The mystery, the fun of ferreting through the clues, and the eventual solution rank up there with “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd” among the author’s first decade of output. Colonel Protheroe, hated by everyone, is found shot to death in the vicar’s house (which is always left open to visitors).

Marple mentions she has seven suspects in mind, so that serves as a bonus puzzle in addition to the question of who actually did it.

Intriguing moral debate

The author dips into an intriguing moral debate via Dr. Haydock, who has the open-minded (and not particularly small-towned) view that criminality is a psychological condition. Clement doesn’t totally agree, but nor is he a justice hawk like the late Protheroe.

Indeed, when one spinster asks Clement to take to the police her piece of information that would bode ill for one suspect, Clement declines.

“Vicarage” keeps the issue in the back of our minds: Yes, someone killed Protheroe, but does that automatically mean they should be hanged? Or is there room for nuance before going to the noose? In chapter 14, Haydock comes to his point:

“We think with horror now of the days when we burned witches. I believe the day will come when we shudder to think that we ever hanged criminals. … I believe the time will come when we’ll be horrified to think of the long centuries in which we’ve indulged in what you may call moral reprobation, to think how we’ve punished people for disease – which they can’t help, poor devils. You don’t hang a man for having tuberculosis.”

So ultimately, we are introduced to Miss Marple without having Miss Marple forced on us; she’s one of several great things about the consistently funny and thoughtful “Murder at the Vicarage.”

Indeed, Marple timidly and modestly (how’s that for a contrast with Poirot?) solves the mystery, not coming forward to the authorities until she has her theory locked down. I see why she became an icon.

Every week, Sleuthing Sunday reviews an Agatha Christie book or adaptation. Click here to visit our Agatha Christie Zone.