Douglas Preston, whose book career began with 1986’s “Dinosaurs in the Attic,” makes a leap in writing quality and, more strikingly, the lengths he will go to for a story, in “Cities of Gold” (1992) and “Talking to the Ground” (1995). Both chronicle his horseback rides through the Southwest – the most untamed parts of the continental United States – while he peppers in historical accounts. Both are engrossing, adventurous ways to learn about the history of the area.

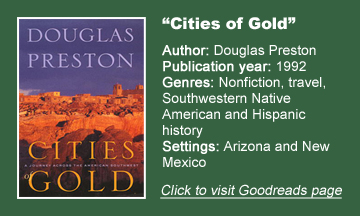

“Cities of Gold” (1992)

“Cities of Gold” is particularly grueling because Preston and neighbor friend Walter, in the spring and summer of 1989, retrace Coronado’s mid-1500s journey from New Spain (Mexico) into what is now America – from southeastern Arizona up to Santa Fe, N.M. (where Preston lived at the time). Preston has no prior experience with horseback riding, and one consultant tells him and Walter there’s a real chance they could die on the journey. As it progresses, those words ring true.

At more than 400 dense pages, “Cities of Gold” is a long journey, paralleling what the author goes through. Books can be the next-best way to “vacation” somewhere you can’t afford to go, and they can also be a better way to experience something that’s dangerous, unpleasant and cost-prohibitive.

Granted, Preston has experiences that a reader can’t have. At one point, he speaks of his brain “popping” into a new, meditative state, and he notes old memories that come back to him – certain that this phenomenon could only have happened on this physically and psychologically challenging journey.

Fascinating Indian history

Despite starting slowly and methodically, I kept enthusiastically going back to “Cities,” even though it took me a couple weeks to read. I learned a ton about Indians. Beyond the basic fact that the Southwestern nations are diminished or outright gone, I appreciated detailed histories of specific nations and what the world has lost by their absence.

The Zuni of northwestern New Mexico, reduced to subsistence-level sheep farming by 1989, particularly stand out as a peaceful, powerful nation that Americans could’ve learned a lot from had the U.S. government not cowed them.

Preston’s writing is wry and zesty. He writes about the bad policies that wiped out the Old West — the too-small land parcels that led to grazing conflicts, and of course the disastrously corrupt Indian relocation schemes. This information makes me angry, but I’m happy to learn it.

Personal side of the journey

The author then switches the mood to the struggles of his individual journey, which – although they are no joke, often involving the essential search for water – are sometimes funny to a reader. It’s absurd how many times the travelers nearly lose their horses. Additional drama comes from the personal conflict between Walter and supposed horse-handler Eusebio (constantly cursing godforsaken Arizona) and, later, spats between the author and Walter.

But it’s heartening how most of the Arizona, New Mexico and Indian Reservation residents are hospitable to the travelers. Preston treats us to descriptions of these colorful characters that would later serve him well in writing fiction. A mountain man named Rod (although that might not be his real name) hunts rattlesnakes to make belts and hat bands, yet he is terrified of them, sure that the rattlers will get their revenge someday.

The book’s big oversight is the lack of photos (especially since Walter takes photos on the trip!) – but at least you can find a gallery online. The map at the front is helpful – I regularly paged back to it. On the trail of Preston’s career, “Cities of Gold” is a monumental achievement.

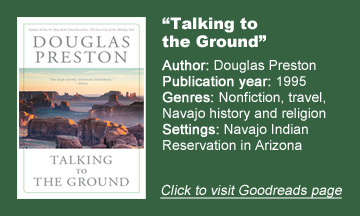

“Talking to the Ground” (1995)

Preston soon became a regular horseman, and he would share more treks with us. Some of those are photography books supplemented by his text, but he makes a return to the narrative format for “Talking to the Ground,” a 1992 journey with his girlfriend Christine and her 9-year-old daughter Selene (soon after, they became his wife and adoptive daughter).

The vast Navajo nation

This adventure is through the Navajo nation in northeastern Arizona; it’s the largest Indian Reservation in the U.S., albeit only covering half of the ancestral Navajo lands. The maps are not very helpful, as they require topographical knowledge, but Preston describes the terrain well and this book does include a center-spread of photos.

The narrative format is identical to “Cities of Gold,” as we cut back and forth between the present day and absorbing history lessons that tie in with the geography. It’s not redundant, though.

This time, Navajo Indians – some of whom are begrudging, especially when the author’s tape recorder appears – give their takes on the nation’s origin mythology, which takes place in the land bordered by four sacred mountains.

In “Cities,” I was impressed by the Zuni’s view of the world as interconnected; here I’m impressed by how the Navajo’s sacred places are in the land, not in buildings like in most major religions. In addition to pure racism and cruelty, the U.S. government’s inability to grasp what their homeland means to Navajos explains a lot of the clashes through the centuries.

The Anasazi mystery

Another thread emerges: the mystery of the Anasazi. In 1992, Preston – based on cited research – had his own theories of the disappearance of those people about a millennium ago, one that ties in nicely with what humanity is a whole is now going through. I’m not a huge environmentalist, largely because federal lands are so mismanaged in alleged service of the environment (as covered in “Cities”), but the Navajo’s love of their land is truly moving under Preston’s keystrokes.

But if you can, get the 2019 printing, because the author’s 10-page epilog goes into a chilling new theory about the Anasazi’s disappearance. Preston nicely ties the new revelations in with the Navajo’s creation myths that (supernatural elements aside) contain solid information about what the Navajo (who came from northwestern North America) saw when settling in this land filled with abandoned Anasazi cave dwellings.

Personal and spiritual

Although Preston and his companions face challenges (such as the all-important search for water, and weather phenomena he’ll use in the novel “Thunderhead”), this adventure is shorter (295 pages) and easier. Preston doesn’t constantly lose his horses like in “Cities.”

The author doesn’t want to make the book about himself, but the personal touches are pretty cute, especially how Selene gradually accepts Doug as her dad. In describing the candy- and Gameboy-loving girl’s behavior, he uses adverbs in a way that J.K. Rowling would later master in capturing young people’s emotional views of the world.

Appropriately, “Talking to the Ground” ends up with a more spiritual feel than its predecessor, partly because the author gives the mic so often to Navajos along the way. But sometimes not literally. One of his interview subjects makes a strong case that Preston will learn more if he’s forced to listen and remember, rather than having to turn to his recording and notes.

Preston takes “the right way” to knowledge by horseback-riding through the Navajo’s holy lands. But of course, we can’t all do that, so “Talking to the Ground” is the next best thing. And as far as “next best things” go, this one is pretty great.