After two bestselling techno-thrillers, “The Andromeda Strain” and “The Terminal Man,” Michael Crichton could’ve branded himself strictly as the master of that genre. Perhaps his publishers wished he would. But with his third book under his own name, Crichton begins to establish himself as a Renaissance man whose interests don’t have borders.

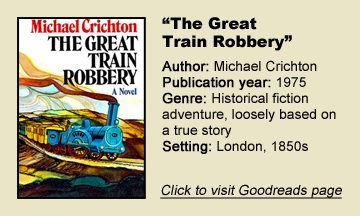

“The Great Train Robbery” (1975) is an adventure novel that, as “Andromeda” does for science, makes history homework thoroughly entertaining.

Bad time to be alive

It’s a little bit fatalistic, though. Not in the sense that we know the outcome of the titular robbery led by the brilliant Edward Pierce (we do know he is brought to trial – thanks to flash-forwards — but not the ultimate outcome), but in the sense that Victorian England is a bad time to be alive.

The planning, the robbery itself and the trial – a fictionalized account drawn from a true story — take place in the 1850s, a time of quickly advancing prosperity, urbanization and speedy travel. But Crichton also points out in great detail all the horrible things about living during that time, if you’re poor.

Among the lower class, sleeping facilities are so cramped that people rent for a penny a night a spot on a series of ropes that they can drape themselves across. Those who don’t have a penny might cram themselves into a corner of an outhouse.

Crichton smoothly interweaves planning and execution of the crime by Pierce and his team with details that teach us about the time. For example, arresting a woman: The Victorian belief was that women were not inclined to be criminals, and that police officers should treat them thusly.

However, the facts showed that some were criminals. As such, an officer who suspects a woman of a crime has a difficult task. For one thing, he can’t search the woman, as that would go against the idea of treating her like a lady. Details like this make the era come alive while illustrating its strangeness compared to modern sensibilities.

Language of the time

The author uses era-based language as impressively as Joss Whedon would later do on TV’s “Firefly,” which – by the way — debuted to TV viewers with “The Train Job.” There, it’s the blending of English and Chinese words in the distant future. Crichton introduces us to historic criminal slang that is no longer used, but we can pick up most of it from context. When we can’t, he translates. The language adds tremendous flavor.

The one area where “The Great Train Robbery” can be dinged is in characterization. Pierce is an engaging enough antihero, but he’s ultimately a cipher; I can see how an actor like Sean Connery could add more verve than what’s on the page.

Crichton sketches basic personalities for everyone, including Pierce’s mysterious mistress Miss Miriam; the key-forger Agar; and the tiny Clean Willy, who can scale nearly sheer walls and get into tiny spaces. He’s a “snakesman,” in criminal slang.

All about the plotting

But we don’t know their full life stories, and they don’t have layers. Relationships aren’t fully played out; Pierce (falsely) develops friendships with some bankers in order to learn where they keep their keys to the safe carrying the gold, but we don’t get post-arrest interactions.

That’s fine with me because that’s not the point of the novel. “The Great Train Robbery” is about the meticulous plotting of Pierce (via Crichton) and the details about Victorian England. The overall vibe is thrilling in its pace and clever scheming, but as noted, it’s also downbeat because of the horrific living conditions of so many people during the rise of urbanism.

The author’s near-futuristic stories, by comparison, have a tinge of hope: Even though they are about things going wrong, we don’t know for sure they will go wrong until they do. Victorian England’s class disparity and imperialism already happened, and the principles became ingrained enough that it’s no accident if a 1975 (or 2021) American reader found these things to be not entirely consigned to history.