Philip K. Dick fans interested in digging into his life are – appropriately – best suited to pursuing the written word, with Lawrence Sutin’s “Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick” (1989) being the most famous and well regarded biography.

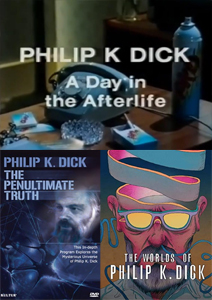

But just as PKD’s works translate to the screen – sometimes well, sometimes awkwardly – his life and career story have also been translated to the screen. Three decent documentaries can be found on YouTube: “Philip K. Dick: A Day in the Afterlife” (from the BBC series “Arena,” 1994), “The Penultimate Truth about Philip K. Dick” (2007) and “The Worlds of Philip K. Dick” (2016).

The many wives of Philip K. Dick

The biggest appeal is putting faces to names as we meet three of Dick’s ex-wives, a couple of his girlfriends, and several of his 1960s-70s Bay Area and L.A.-area friends. Among the wives – the people who knew Dick best on a day-to-day basis — second wife Kleo is in “Afterlife,” third wife Anne is in “Afterlife” and “Penultimate,” and fifth wife Tessa is in all three.

“Philip K. Dick: A Day in the Afterlife” (1994)

Director: Nicola Roberts

“The Penultimate Truth about Philip K. Dick” (2007)

Director: Emiliano Larre

Writer: Patricio Vega

“The Worlds of Philip K. Dick” (2016)

Director: Yann Coquart

Writer: Yann Coquart

The most eyebrow-raising guest expert is Dick’s psychotherapist Barry Spatz, who appears in all three. It’s rare that a therapist will be so open about a patient, even a deceased one. Spatz’s somewhat playful reflections on Dick’s agoraphobia and other conditions are surprising.

The documentaries explore Dick being attracted to psychologically damaged women, which is amusing since Kleo, Anne and Tessa are all (mature and cogent) interview subjects. They recall good and bad things about their husband, which makes sense since they all married and divorced him (only in Anne’s case was the divorce more Dick’s idea).

First wife Jeanette is presented as a mystery in “Penultimate,” as no one knows what happened to her (!). Fourth wife Nancy is portrayed as the most psychologically troubled, and her fate is left as a plot hole.

Searching for the truth

It’s no surprise that all three documentaries gravitate toward the mystery of what the Dickheads Podcast dubs “the pink laser beam of truth” – Dick’s contact with God (perhaps) in February 1974. Tessa corroborates the incident, but of course can’t go into Phil’s mind.

But she does back up the later story that Phil got a subliminal message about their son Christopher’s life-threatening hernia – something neither parent had the medical knowledge to understand – and they then took him to the hospital where doctors confirmed the God-beamed diagnosis.

“Penultimate” is the longest of the three – at about 90 minutes, compared to 60 for the others – and the most balanced in presenting possible explanations about the pink beam era. Girlfriend Joan Simpson believes Dick’s 1977 Metz conference speech was an embarrassment, and friend K.W. Jeter seems annoyed by Dick’s craziness (and then expresses relief that Dick’s final novel, “The Transmigration of Timothy Archer,” turned out so grounded). But friend Tim Powers believes PKD did receive a supernatural information download.

Another possibility, proposed by some interviewees, is that Dick was engaged in a long con of self-mythologizing, wherein the concepts of belief and sanity were games with ever-changing rules. It’s up to each PKD fan to decide. I personally lean toward him not being crazy, but more open to surreal possibilities than the average person.

Sometimes he took it too far. But on the other hand, some interview subjects categorize Dick as paranoid for suggesting that the early 1970s break-in at his Bay Area home might’ve been done by the government. It’s well documented that the FBI was keeping an eye on Dick; labeling him as an anti-government paranoiac is lazy.

In his own words

These documentaries aren’t as thin on exploring Dick’s novels and stories as I’ve made it sound. None do deep dives, but they do nicely pepper in PKD’s written words. Narrators Greg Proops (“Afterlife”) and Franck Desmedt (“Worlds”) read passages from his fiction and philosophical writings; in “Worlds,” citations helpfully appear on screen.

At times, other authors discuss Dick’s works, including Thomas M. Disch in “Afterlife” and David Brin in “Worlds.” In “Afterlife,” SF director Terry Gilliam’s passion comes through as he simply describes the plot of “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”

In “Worlds,” biographers Anthony Peake (“A Life of Philip K. Dick: The Man Who Remembered the Future”) and Gregg Rickman (“Philip K. Dick: In His Own Words”) are featured, with Rickman’s audio recordings of interviews with Dick helpfully providing the late author’s voice.

All three documentaries use stylistic framing devices. “Afterlife” riffs on “Ubik” by imagining products with “PKD” labels (and getting surprising celebrity cameos, including Elvis Costello!); “Penultimate” enacts FBI agents going through “files” on Dick; and “Worlds” uses archival stock footage to evoke the midcentury. “Penultimate’s” FBI gag is a bit much, but in no case do the trappings overwhelm the interviews.

While there’s some overlap in themes, you can watch all three without too much redundancy. These documentaries aren’t the place to go for deep dives into Dick’s writing; that’s fine, because we can get that from scholarly articles and freewheeling discussions like those on the Dickheads Podcast. But they do reveal a fair amount about how PKD lived, thanks to interviews with the people who knew him best, and all three can function either as entry points or light entertainment.

“Philip K. Dick: A Day in the Afterlife” (BBC, 1994): 4 stars

“The Penultimate Truth about Philip K. Dick” (2007): 4 stars

“The Worlds of Philip K. Dick” (2016): 4 stars