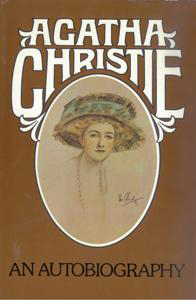

In “Agatha Christie: An Autobiography” (1977), Christie famously doesn’t go deep into analyzing her novels or the stories behind them. That might’ve been frustrating in 1977, but with so much scholarship out there now, it’s less of a problem. And besides, Christie (1890-1976) was genuinely shy and modest. We wouldn’t want nor expect her to be any other way in her memoirs.

The bulk of this 500-plus-page doorstop is about her formative years (with lots of great universal observations), her love of her childhood country home Ashfield, family and friends, and her time on Middle Eastern archeological digs with her second husband, Max Mallowan, in the Thirties and Fifties. Although she observes other people more so than writing about herself, she is giving us her personal take on other people.

Observer of people

Christie gives a sharp insight into a perhaps universal trait of humans in part VIII. She observes that people are most themselves at age 6 or 7, then they put on a show of being someone else around 20, then as life goes on “you relapse into individuality.”

Christie parallels this with writing, noting that you begin as an imitator and eventually find your own style. There’s a comfort in both being yourself and using your own style, because although you might not be the best person nor the best writer, you’d be worse if trying to be something you’re not. This is why she was satisfied to try her hand at music (piano playing and singing) and fail, knowing that’s not where her strengths reside.

It’s hard to say if Christie was more of an individualist or a collectivist, but naturally someone who lived her 85 years in one of the most rapidly changing 85-year stretches of human history would have contradictions. As emphasized in “Ordeal by Innocence,” she believes strongly in the value of victims’ lives and less so in culprits’ lives.

In “An Autobiography,” she writes a controversial passage about how locking criminals in cages isn’t a humane solution (I agree) and that perhaps offering them chances to serve in medical experiments would be a more humane approach. If they survive the experiment, they go free and get another chance to be a good citizen. I have a problem with this, but that’s mainly because I have less faith in the government to catch the correct people than Christie does. Still, I admire her for diving into a topic most people would rather not discuss.

Something’s missing, but that’s OK

Christie’s focus on her childhood and the Iraq and Syria digs will seem redundant to those who have read her Mary Westmacott novels (three of which are heavily autobiographical) and “Come, Tell Me How You Live” (1946), her archeologically focused first autobiographical work.

“An Autobiography” is infamous for not featuring anything about her 1926 disappearance, although she does believe the first novel she wrote after that, “The Mystery of the Blue Train,” is her weakest because of her inability to focus or care. The autobiographical Westmacott novel “Unfinished Portrait” suggests that Christie had a mental health breakdown under the pressure and surprise of her mother’s death and first husband Archie leaving her.

She temporarily forgot who she was, and although she’s embarrassed by it, she hints at it in a passage where she reflects on increasing knowledge about mental health. She’s always been consistent that she had temporary amnesia amid a mental breakdown. Since she’s not known for lying about any other aspect of her life, it’s bizarre that some people suspect she is lying, and search for a mysterious, secret explanation for her disappearance.

A few words about her own work

Christie also skimps on writing about her own writing, although her point that it took her a long time to realize she was a “professional” writer – well into the Thirties, after she became famous – is a fascinating reminder that married women’s jobs at that time were generally “housewife.” Her passion for theatrical writing – as something she could do without pressure, since she could count on money from her annual novel – makes me want to delve into her stage plays.

Writing mostly in chronological order, but sometimes going on tangents, Christie peppers in comments on her novels. Surprisingly, she was proud of “Ordeal by Innocence” and “The Moving Finger,” two mysteries not high in most readers’ rankings. Not surprisingly, she was proud of “And Then There Were None” (a widespread reader favorite), not necessarily because she expected everyone to love it, but rather because it was a huge challenge she successfully tackled.

I’m heartened to know she was proud of “The Rose and the Yew Tree” and “Absent in the Spring” (which she wrote in a few days, calling in sick to her wartime nurse’s post). I find these two Westmacotts to be under-heralded masterpieces that rank with her elite detective novels.

It might take you a while to read it because it’s long and dense (and a little redundant, but not overly so). You’ll enjoy most of your time with “Agatha Christie: An Autobiography” if you’re already a fan. It won’t satiate your desire to learn everything you can about the author, but since 1977, she has become a thoroughly analyzed historical figure. As such, the autobiography comfortably stands as Christie’s chronicle of what mattered to her.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews an Agatha Christie book or adaptation. Click here to visit our Agatha Christie Zone.