Janet Morgan’s “Agatha Christie: A Biography” (1984) is the estate-approved life story of the author, and still stands as the most definitive. I’d recommend reading both this and Christie’s “An Autobiography” (1977) but with some space between them. There is some overlap of content, with Morgan sometimes citing the autobiography.

The biographer also lavishly cites Christie’s story idea notebooks (which were later published outright) and correspondences with her agent, Edmund Cork. She was a regular letter writer — perhaps that’s how most people were back then? — and she and Cork did a great service by saving these exchanges.

Between this, the autobiography and “Come, Tell Me How You Live” (1946), we get perhaps more of Christie’s Middle East adventures with second husband Max Mallowan than we might want. But it does drive home the point that “archeological assistant” was her significant second career.

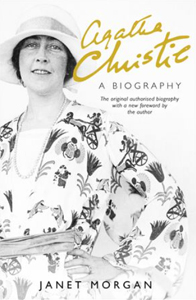

“Agatha Christie: A Biography” (1984)

Author: Janet Morgan

Genre: The official biography of the author (1890-1976)

The biggest advantages of Morgan’s book over Christies’ are that it’s in strict chronological order and almost all the books and plays are mentioned. When a book or play comes up, this is the one time Morgan inserts a little of her opinion into the text. The author has some surprising views; notably, she finds some of the oft-denigrated later novels (like “Passenger to Frankfurt,” “Elephants Can Remember” and “Postern of Fate”) fascinating and ambitious.

At the same time, Morgan cautions us against assuming too much autobiographical material in the Mary Westmacott books. She notes that “A Daughter is a Daughter” (1952) is not based on her relationship with her daughter, Rosalind, nor her mother, Clara.

Truth is stranger than fiction

Those interested in Christie’s 1926 disappearance will enjoy “A Biography” after being snubbed in “An Autobiography.” I find it bizarre that so many false accounts popped up in the media – at the time, sure, but also after the facts were revealed. The truth – that Christie had temporary amnesia – is as fascinating as any of the fictional accounts (although Morgan’s chronicle of the inaccurate newspaper reports is engrossing in its own way).

Having not delved into Christie’s plays yet, I enjoyed Morgan’s robust account of her subject’s theatrical career. The unfortunate thing about theater is that we can’t go out and see most of these plays on a whim, but perhaps I’ll read the stage plays sometime.

Morgan doesn’t go into the film, TV and radio adaptations quite as deeply, content to drive home the point that Christie generally hated them. Since none of these productions had Christie’s direct involvement, it’s a fair decision to skim over them.

Fans (or critics) of Christie “continuations” (works that feature her characters in brand-new stories, such as Sophie Hannah’s new Poirot novels) might be interested in the reminder that this controversy goes back as far as 1964. The last of the four Margaret Rutherford-starring Miss Marple movies, “Murder Ahoy!” (1964), featured a non-Christie story.

Combined with the widely held view that Rutherford’s Marple has little in common with Christie’s Marple beyond the name, we can sympathize with Christie’s stance that it’s unethical to write a new story about someone else’s character.

A taxing career

Speaking of frustrations, readers’ blood might boil at the accounts of Christie’s struggles with income tax collectors in both the US and England. Not everyone agrees that taxation is theft, but Morgan makes a strong case that it is. At one point 90 percent of Christie’s book earnings went to the UK government, 10 percent into her pocket.

Combined with the legal confusion and the lawyers’ fees, it’s clear that taxation caused Christie stress both in terms of actual money and the lack of clarity about her money. It’s a shame that she (or anyone) should have to deal with that just because they choose to do a job.

For someone who became increasingly irked about interviews and photographs, Christie wasn’t precisely hiding. She valued privacy, wanting to be a person, not a celebrity. But she did leave all those notes and correspondences, plus the two autobiographical accounts. She understood her cultural legacy and the fact that people were interested in her life.

Morgan takes the next step after “Come, Tell Me How You Live” and “An Autobiography,” painting a sober portrait that reads like a good novel – albeit like a Westmacott more than a mystery or thriller. While there’s room for new insights and angles in other biographical works (including deeper thoughts about Christie from people who knew her), “Agatha Christie: A Biography” will always rank as an engaging, thorough chronology.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews an Agatha Christie book or adaptation. Click here to visit our Agatha Christie Zone.