The “Ghost World” graphic novel (1997) is not as good as the later film adaptation, but that’s a high bar to clear: The 2001 movie challenges for the honor of my favorite film of all time, going back and forth with “Garden State” (2004). Still, I admire Daniel Clowes’ comic, and also acknowledge that he co-wrote the superior film.

Clowes and co-writer/director Terry Zwigoff lift several scenes from the source material verbatim. They are always sequences for the sake of tone and humor, not for plot, but they are nonetheless important in establishing the wandering, curious, mean-spirited, decent-hearted Enid and Rebecca (Thora Birch and Scarlett Johansson in the movie). (The film also borrows from several other Clowes comics, as this article by Will Forbis outlines.)

The celluloid “Ghost World” is softened by Birch being innocently baby-faced, so therefore her explorations of different fashions and music tastes always have a touch of adorableness. Even my friend Michael, who argues that Enid’s behavior in the film is unsympathetic, acknowledges that Enid is likable and good at her core.

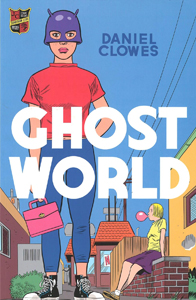

“Ghost World” (1997)

Graphic novel, originally published in “Eightball” Issues 11-18 (1993-97)

Writer: Daniel Clowes

Artist: Daniel Clowes

Genre: Teen drama

Setting: 1990s, unnamed American town

Before the cinematic gloss

But now we get to where the comic is significantly different from the movie. Enid (whose full name Enid Coleslaw is an anagram for Daniel Clowes) and Rebecca aren’t drawn as cutely – indeed, Clowes puts an ugly realism into everyone he draws. Remarkably, the famously funny looking Steve Buscemi (although, yes, we must acknowledge the phenomenon of women finding Buscemi attractive) plays a character unique to the film named Seymour.

Visually, Seymour has a comic equivalent as a Don Knotts-looking fellow who tells Enid he believes the quiet, odd couple in the corner booth are Satanists. Then Enid and Rebecca run with that gag, whereas in the film, they originate the theory.

Other comic scenes and sequences are repurposed for Seymour. The girls – along with the unwilling Josh (Brad Renfro in the film) – play a mean prank on a stranger, luring him to the restaurant to meet a nonexistent date. The stranger realizes the teens pranked him and curses them out, whereas in the film Seymour is oblivious, and it’s a sympathetic way to launch his arc.

In the comic, Josh is an object whom Enid uses in her attempt to be normal – awkwardly and lazily trying to seduce him. This arc becomes Seymour’s in the movie, with additional layers since Enid genuinely relates to Seymour as a fellow outsider. And also with the fascinating undercurrent of him being inappropriately old for her, by late 20th century American norms.

Buscemi is such a presence in the film that he becomes a co-lead with Birch, and “Ghost World” can even be watched from his perspective.

A subtly different Enid-Rebecca conflict

Clowes’ comic, lacking Seymour, has a different aim, although it’s a sub-arc in the film, too: the reshaping – and perhaps end — of the friendship between Enid and Rebecca. Not from either of them doing anything notably bad, but simply because they grow apart due to having different immediate goals.

Films often simplify concepts from the source material, and “Ghost World” is no exception. In the movie, Rebecca is able to find contentment by entering the flow of mainstream societal values, whereas Enid doubles down against the normies and hopes for a path where she can be herself and still be happy.

To create narrative momentum, the movie presents Enid with options that are tantalizingly, barely out of reach: Romance with Seymour, who is too old for her (in terms of societal norms, yes, but also in terms of long-term stability) and a free-ride college art scholarship. The latter option is obliterated by a blast of local political correctness at an art exhibit that unfairly undercuts the career paths of both Enid and Seymour.

In the comic, it’s subtler. Although she can’t openly admit it, Enid is curious to see what she’ll be like without Rebecca at her side. With a potential college admission as the excuse, she desires to move to another town. Rebecca – able to find contentment anywhere – is interested in moving there with Enid; as youths, they had always talked about getting a first apartment together. Like Jay says of Silent Bob, Enid is Rebecca’s heterosexual life partner.

Enid meets Holden

Clowes’ comic is in the same genre (coming-of-age) and style (a series of vignettes, rather than a grand plot) as J.D. Salinger’s novel “The Catcher in the Rye” (1951). Due to the Salinger estate’s rule against it, it won’t be adapted into a film (nor does it really need to be). But if it were, we’d likely see something like the “Ghost World” situation in that Holden Caulfield would become more likable simply by being played by an actor on a screen.

The parallel between Salinger’s and Clowes’ touchstone achievements goes further in that both Holden and Enid are unlikable on the surface. Holden is a good person who thinks of other people’s feelings, but that trait outwardly manifests as him being annoying. He’s so desperate for conversational connections that he drives people away.

Enid’s life in Clowes’ comic consists of her mocking strangers and devising pranks against some, and regularly ribbing and saying “F*** you” to her best friend. (It should be noted that that’s how teens talked in the Nineties, and Clowes, in his 30s at the time, was likely interested in capturing this crass phenomenon).

Not first-person like “Catcher in the Rye,” “Ghost World” gives us omniscient, sympathetic glimpses into the fragile psyche of the outwardly mean Enid. Notably, she believes she is going “crazy from sexual frustration,” but fascinatingly, her love life is defined by her desire to be normal – even though she outwardly acts like being a normie is the worst thing a person can be.

She wants to lose her virginity in order to be normal, and fantasizes about an attractive teacher popping up on her while she’s showering. Then she does seal the deal with a slightly older student, but is oblivious to him truly liking her (an aspect that the film would borrow for Seymour). Then she puts awkward moves on Josh, whom she isn’t actually drawn to, in order to have a “normal” boyfriend. (Off-panel, we can presume Rebecca is doing things “correctly” with Josh.)

A time capsule of the Nineties

It was the Nineties and this is an indie comic, so when Enid says to Rebecca “Maybe we should be lesbos!” it can be taken both as dark humor and as a suggestion that this is a coded story of best friends who could become lovers.

Perhaps Enid’s desire to not be seen as normal in terms of fashion and behavior – but also, contradictorily, to do “normal” things with boys — stems from a sexual attraction to Rebecca? Such a reading is there for those who want it, but it can also be breezed over by those who don’t want it.

In either reading, Rebecca wants different things than Enid, and they drift apart. Incongruously, while the film would later put the end of this relationship in a bittersweet-at-best light, Clowes – so pitch-black in his portrayal of Enid – has Enid be secretly sweet toward her bestie, wishing her well from a distance as she sees Rebecca and Josh on a date.

The “Ghost World” comic ultimately plays as an empathetic writer/artist pouring out shallow vitriol (some of his own, along with a healthy dose of what he observed in Nineties teens) before admitting to his sentimentality in the final pages. By then, the showy anger has morphed into a deeper, universal statement about the natural and unavoidable tragedy of the hormonally confused teenage mind.

Clowes’ “Ghost World” is a sad story, but not a hopeless one. Salinger’s Holden got out of his predicament with off-page psychological help, and we sense Enid will too. We know that, by definition, she will eventually move past this psychological condition known as “being a teenager.”