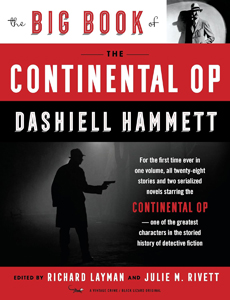

In collecting all of Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op stories (1923-30), “The Big Book of the Continental Op” (2017) brings a reader back to the excitement of a century ago when the author was inventing the hardboiled detective fiction genre. Largely this is through the stories themselves (28 shorts, some of which tend toward novella length, plus the original serialized versions of the two Op novels). But it’s also through the Black Mask Magazine editors’ introductory blurbs.

Getting the job done

While the blurbs are often breathless hype, they also indicate the editors were aware of this new “men’s fiction” as it was happening. They are a nice addition to this collection curated by Hammett scholars Richard Layman and Julie M. Rivett. While the stories themselves contain traditional thrills – notably brawls featuring realistic pain and physical awkwardness – the biggest takeaway is that the Op is doing a job. His satisfaction, and ours, comes from a job well done.

The efficiency comes from Hammett writing what he knows. He had been a Pinkerton detective (and some stories are drawn from real cases, and the Op’s San Francisco branch colleagues are based on Hammett’s). And also from Hammett’s to-the-point style, as illustrated by the one unfinished tale, “Three Dimes.” While this rough draft allows us to understand the importance of magazine editors, it also suggests editing Hammett’s work must’ve been a pleasure.

“The Big Book of the Continental Op” (2017)

Collects the 28 stories and two serialized novels (1923-30) featuring the detective

Author: Dashiell Hammett

Editors: Richard Layman, Julie M. Rivett

Genre: Hardboiled detective short stories and novellas

Settings: 1923-30, San Francisco, etc.

After finishing this 733-page, doubled-columned doorstop (except the “Red Harvest” and “Dain Curse” serialized versions, which account for 210 pages, since I had read those novels recently), I wanted to go back and start over again. It’s a blast to spend time in this world.

You might assume the Op leads a lonely, workaholic existence, but that’s not the vibe I come away with. Because he’s unnamed, there’s an unspoken agreement between author and reader that the Op will be defined as a working agent in these pages. Maybe his non-work life happens outside the words, maybe not.

While the magazine editors (“Big Book” has essays about the influence and approaches of Sutton, Cody and Shaw) see Hammett as codifying “men’s fiction,” and while the stories are in first-person narration, the Op doesn’t hide his feelings in the stereotypical manner of the male gender. Since he doesn’t know he has an audience, he does admit to – for instance – having his feelings scrambled by femme fatales. The Op isn’t Hammett’s experiment in keeping personality out of crime solving; those moments of humanity are the exceptions that prove the rule that the Op is good at his job.

The century of progress

While Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories (1887-1927) are often set in the recent past — a gaslit turn-of-the-century London – Hammett writes in contemporary times and takes us to America in the 20th century. We sense the progress ahead, and I bet 1920s readers did too.

Even so, “Big Book” reminds us there will always be murderers, thieves, fraudsters – and, in one memorable story, a corrupt cop. This makes the Op’s work timeless and grinding, rather than romantic and superhero-ish. He’s the Batman to Holmes’ Superman – except he’s not rich. In “This King Business,” the Op finishes brokering a multimillion-dollar transfer of power in a Balkan state. Deadpan, the Op concludes: “I went back to San Francisco to quarrel with my boss over what he thought were unnecessary five- and ten-dollar items in my expense account.”

It’s a fun line, but not an unusual line, because the Op always speaks deadpan and thinks deadpan. This would become a trait of “hardboiled,” along with the idea that he’ll do the job within the rules – maybe slightly outside them, sometimes – and try to not get beat up, but if he does, he’ll deal with the injuries.

While my heart warms at cozy Bay Area crimes like kidnapping and insurance fraud, I don’t mind when things get bigger. This occurs with the Op’s international assignment in “This King Business”; “Corkscrew,” where he’s deputized in Arizona to probe a murder spree; “Dead Yellow Women,” where he must navigate language and cultural barriers in Chinatown; “The Gutting of Couffignal,” where he thwarts the sacking of a rich island community off the California coast; and “The Big Knockover”/”$106,000 Blood Money,” where dozens of the biggest gangsters in the USA converge for a series of bank heists.

Increasingly bigger cases

Hammett is building to the Op’s biggest mission, “Red Harvest” (“The Cleansing of Poisonville” in magazine form), where he methodically ends a mining town’s deeply rooted corruption by strategically pitting various corrupt-government and outright-criminal factions against each other. It’s his greatest accomplishment, and rightly the most famous tale.

Fascinatingly, Layman points out that some critics prefer the serialized version of “Poisonville” over the novel “Red Harvest.” While the story is the same, almost every paragraph has an edit of some kind, so the serialized version is the purest Hammett. The next time I have a hankering for “Red Harvest,” I’ll indulge in “Big Book’s” version.

Speaking of poisons, arsenic poisoning (later a favorite murder method of Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers) plays a part in “Fly Paper.” The real-world tool of fingerprinting comes into play in “Slippery Fingers,” and “Big Book” includes Hammett’s thoughts and rebuttals in the Black Mask letters column over whether fingerprints can be transplanted to a crime scene.

Hammett didn’t use short stories as test runs for novels to the degree Christie would, but one story will be of particular interest to “Thin Man” fans: “The Farewell Murder” almost directly becomes the movie “Another Thin Man,” with Nick Charles stepping in for the Op.

“The Big Book of the Continental Op” is for completists (even if you have acquired the material elsewhere, the essays and footnotes on the meaning of now-out-of-date words and phrases are worth it if you can find the book cheap). But it’s also for casual fans of hardboiled detective fiction, because there’s no bad Op story. I took my time, dipping in for a story here. Although the prose flows like a winding river, each story is dense with logistics and connections, and you’ll want to hold the general shape in your brain. A single-sitting read of each story is ideal.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews the works of Agatha Christie, along with other new and old classics of the mystery genre.