For the 20th anniversary of “Harry Potter,” I’m looking back at the books and films of J.K. Rowling’s Wizarding World saga.

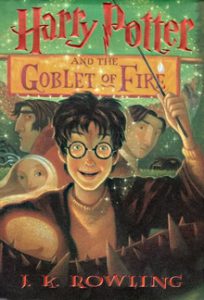

After three books that weighed in at no more than 435 pages, “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire”(2000) kicks off a four-book run of doorstops with a 734-page tome. J.K. Rowling uses the extra pages to give us more details about the logistics of the Wizarding World, and she also successfully delves into using different tones and – arguably – different points of view.

The first three books were all from Harry’s perspective, but “Goblet of Fire’s” opening chapter, “The Riddle House,” seems to be a backstory of the Riddle family, with Frank Bryce, the longtime caretaker of the Riddle property, as the primary POV character. One could argue this chapter is still from Harry’s POV, since we learn in the next chapter that it was his dream-vision (albeit one of actual reality, thanks to his psychic link to Voldemort). But it’s still a decidedly different way to open a “Harry Potter” book.

One of the most interesting talking points about “Goblet of Fire” is something that barely affects the plot at this point: Hermione’s interest in the plight of house-elves. In the earlier books, it seemed like food magically appeared on the students’ plates in the Great Hall, leading one to suspect wizards can magically create food – and thus perhaps providing a solution to poverty and famine. “Goblet of Fire,” though, reveals that while the food is magically transported to the tables, it is actually prepared in the kitchen by house-elves.

In this book, Rowling makes it clear that – for all the ways the Wizarding World is more advanced than the Muggle world (in the sense that magic is often better than technology) – it has many of the same problems. The Ministry of Magic is as corrupt as any Muggle government, as starkly illustrated in the final chapters when Minister Cornelius Fudge refuses to believe that Voldemort is back, because that would mean he’d have to make decisions about what actions to take, thus opening himself up to criticism from the electorate. This forces Dumbledore and his allies to work behind Fudge’s back to prepare for the coming war.

Inevitably, each book builds the Wizarding World a bit more, but Rowling seems to deliberately answer some questions here. In addition to introducing the role of house-elves in Hogwarts, she explains how magical locations remain hidden from Muggles. Indeed, the massive Quidditch World Cup stadium and its surrounding campgrounds must be magically hidden: “Every time Muggles have got anywhere near here all year, they’ve suddenly remembered urgent appointments and had to dash away again,” Mr. Weasley explains in Chapter 8. Additionally, wizards occasionally use plain old “Obliviate” spells on the Muggles who believe they are overseeing a large camping festival.

Rowling also confirms that – as one might expect – the Wizarding World is global. While she’ll save her exploration of America’s relationship with magic for the “Fantastic Beasts” series, here she introduces the rival wizarding schools Durmstrang (somewhere “up north”) and Beauxbatons (presumably in France, though it’s not explicitly stated).

The Wizarding World actually lags behind the Muggle world in the area of slavery, as house-elves are not paid for their labor, nor do they want to be. In “Goblet of Fire,” Hermione would find sympathy with Harriet Tubman – famously quoted as saying “I freed a thousand slaves. I could have freed a thousand more if only they knew they were slaves.” Through her nascent political movement S.P.E.W. (Society for the Promotion of Elfish Welfare), she tries to get the house-elves to unionize, but runs into a brick wall not only from her friends (Ron tells her that the elves like their lot in life) but from the elves themselves, who fear freedom.

The lone exception is Dobby, who has a paid job at Hogwarts because of Dumbledore’s decency but could not find one elsewhere. In addition to the value of (non-coerced) unionization, this calls to mind the importance of individuals asking for and accepting appropriate wages, rather than working for too long for mere “experience.” I’ve noticed the issue particularly comes up in the professions of live music, where mid-level bands are squeezed out at one end by those playing for experience and at the other end by bands who have made it big, and also in writing, where some websites are filled with people writing for the sake of building a resume, squeezing out established journalists.

Speaking of journalism, “Goblet” warns against the dangers of accepting news reports at face value through the character of Rita Skeeter. Despite being widely known as a muckraker, she still has the Hogwarts populace eating out of her hand as she rips Hagrid, Harry and Hermione in various articles (and at one point writes an over-the-top puff piece about Harry, thus making everyone hate him). Even Mrs. Weasley is not immune to this: She turns cold toward Hermione after reading Skeeter’s hit-piece about how Hermione is toying with the affections of Hogwarts boys, and only snaps back to reality when Hermione herself sets the record straight.

This is heady stuff for a book presumably aimed at 14-year-olds (as that’s Harry’s age here), but Rowling doubles down on her belief that kids can handle adult stuff – not only in the sense of serious things happening (like Cedric Diggory’s death) but also in the sense of being open about it. The Ministry’s official position is that students should not be told that Voldemort murdered Diggory, but Dumbledore tells the assembled Hogwarts students anyway in Chapter 27: “… they think I should not tell you, young as you are. It is my belief, however, that the truth is generally preferable to lies.”

That’s not to say that “Goblet” is a blunt instrument (even if it is thick enough to stop a bullet): Rowling uses a deft touch in shifting tones. The middle portion – featuring the refreshing challenge of the Tri-Wizard Cup, where Harry competes against Hufflepuff’s Cedric, Krum from Durmstrang and Fleur from Beauxbatons – is as fun as ever. The author shifts tones while staying true to the world she has established. For example, before things get really serious, Harry says “Cockroach Cluster!” as the password to Dumbledore’s office. After Cedric’s death, Rowling merely writes “Dumbledore gave the password,” signaling that this is a time to be serious.

When a reader closes “Goblet,” they are left with the impression of Cedric’s death and Harry’s showdown with Voldemort, but the book is packed with grin-worthy lighter material. We get great new creatures, like the blast-ended skrewts, which of course are beloved by Hagrid despite being extremely dangerous (one end is a pincer, the other end is essentially a firework). “Goblet,” to my delight, also introduces the jewelry-hoarding nifflers, which gained a resurgence in popularity with their appearance in the “Fantastic Beasts” movie.

We get another good mystery – who put Harry’s name in the goblet, and for what reason? – with a surprising answer that holds together quite well. This leads to an oddity: The book’s best new character, Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher Mad-Eye Moody, is not actually the real Mad-Eye Moody – he’s Barty Crouch Jr. posing as the professor in order to be in position to manipulate Harry in the service of Voldemort.

And the evocative Yule Ball is part of why the “Potter” series feels Christmassy, even though each book covers a full school year. It’s ridiculously cute how Ron is jealous of Krum for taking Hermione to the ball, without realizing he is jealous, and how every time a character is faced with a romantic issue – for example, Harry asking Cho to the Yule Ball – they turn red. (Impressively, Ron turns purple at one point when talking to Fleur.)

For all the challenges Harry conquers here – for the record, he technically wins the Tri-Wizard Cup, of course – there’s one he has yet to master: Talking to girls. That’s a higher-level challenge for another year.

Movie review: “Goblet of Fire”

Next book: “Order of the Phoenix”