“A Study in Scarlet” (1887), Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel and a formative entry in the burgeoning mystery genre, remains entertaining 137 years later. It also features elements very much of their time – sometimes in endearing ways, sometimes in shocking ways. And I can see how the next century’s queen of mysteries, Agatha Christie, built upon what Doyle sets up.

“Scarlet” – the title of which, like Dashiell Hammett’s “Red Harvest,” apparently alludes to the bloodiness of the tale – is a page-turner that can be knocked off in a few sittings. But it starts with the pleasant deliberateness of the 19th century.

Dr. John Watson, a war-veteran narrator who Christie’s Hastings is blatantly patterned after, is short on funds and needs cheap lodging. In a reminder of a time before runaway inflation, he’s able to secure a nice apartment with a roommate, Sherlock Holmes, who makes his living as a “detective’s consultant,” a job he has pioneered.

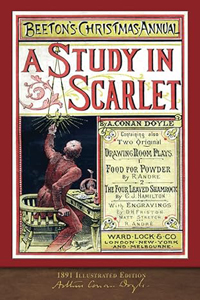

“A Study in Scarlet” (1887)

Author: Arthur Conan Doyle

Series: Sherlock Holmes No. 1

Genre: Procedural mystery

Setting: 1887, London, with flashbacks to Utah

It’s been said that Holmes doesn’t have a personality, but it’s more accurate to say he has an atypical personality that stems from his unusual way of thinking. He plays the violin (not in annoying fashion), and is considerate of Watson in multiple ways.

Holmes warns his new roomie about his antisocial stretches before Watson signs the papers. He uses Watson as a sounding board, and also invites him along on clue- and information-gathering missions. While Holmes is arrogant (but he earns it, as he’s clearly the smartest man in any room), he does not insult Watson the way Poirot insults Hastings.

We appreciate Holmes, but aren’t allowed to participate

The reading experience of “Scarlet” is pleasurable in a similar way to Christie’s debut of 33 years later, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles.” And Christie would borrow the hook of a corpse found in a random location for “The Body in the Library.” But it’s interesting to note that not all of the mystery genre’s tropes are in play. Notably, this is not a whodunit; we aren’t offered multiple suspects to mull over. It’s not a puzzle to solve; it’s a story to follow.

This isn’t a major flaw, since Doyle is a smooth storyteller out of the gates. (For many years, this was treated as his debut novel, but 1883’s “The Narrative of John Smith” was discovered and published in 2011.)

Doyle shifts gears midway through “Scarlet.” In the first part, he solves the murders of two men, capping it off by luring the killer to his flat while Scotland Yard inspectors Gregson and Lestrade are alternately consulting with him and bragging of their (seeming) success.

A long flashback makes up the book’s second half, which jumps into the Western genre with surprising ease and gives a controversial portrayal of Mormonism that’s more damning than the 2023 miniseries “Under the Banner of Heaven.” Here we learn the backstory of the killer and the two deceased men; it’s a great tale steeped in one man’s understandable but impressively maintained thirst for vengeance.

Interestingly, though, the yarn is for Watson’s and the readers’ benefit, as Holmes doesn’t need these details to solve the case. Fascinatingly, he explains the crux of his method to his new roomie: Holmes analyzes backward rather than forward. He looks at the result and figures out the steps that led to the result. Most people (he correctly notes) are good at looking at steps and guessing the result, but not the reverse.

It’s a dog-eat-dog world, but Holmes isn’t wearing Milk-Bone underwear

This is fiction, though, so Doyle leans on some smile-worthy conveniences. Holmes guesses there was a nosebleed at the scene so assumes the killer is a ruddy-faced man. This strikes me as a stretch to the same degree that widely spaced footprints pointing to a tall killer is a sharp deduction.

Along with occasional casual racism, such as street urchins being colloquially called “Arabs,” one of-the-time element is rather harrowing. Holmes, who has a lab set up in the flat, needs to find out if a pill is poisonous, so he grabs a dying terrier off the street and feeds it the pill. The dog dies, and he has his answer.

While Doyle emphasizes the dog’s sorry state and doesn’t mention any convulsions (even though the human had died with a horrific rictus on his face), thus softening the blow for readers, it’s nonetheless remarkable how the dog’s life is of no interest to Holmes, Watson or the Scotland Yard inspectors.

So, yes, the novel is somewhat the cold, calculating experience you’d assume as Doyle launches an icon and begins to codify a genre. But there’s also some welcome warmth (the friendly relations between roommates), humor (Holmes laughs off the fact that the police sleuths get the official credit) and atmosphere (pouring rain in a key scene).

As has happened to countless readers who have embarked on the Doyle journey, “A Study in Scarlet” easily hooks me enough to continue my trek into the other three Sherlock Holmes novels and 56 short stories.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews the works of Agatha Christie, along with other new and old classics of the mystery genre.