We’re in a curious situation right now where 94 percent of the country supports pro-war presidential candidates yet other polls show that the majority of people are against war (although most of Congress is pro-war). Of course, war is a complicated issue, and I don’t pretend to understand all of it (although I certainly respect soldiers’ views, which tend to lean anti-war, in my experience). But because of the mainstream media’s focus on the two major parties, the raw fact of our involvement in the Middle East is generally not questioned — rather, the questions are about the details of how to conduct the wars.

But this fall, dramatic television has brought the wider theme of war — the cycle of violence, the cost in human lives and the crushing of a soldier’s psyche — onto the public stage. Most notably, there’s the new series “Last Resort”: Sub commander Andre Braugher refuses a direct order from the president to turn Pakistan into Superman’s apartment (fire and sand make glass). So another U.S. sub fires on his sub, which escapes and sets up a banana republic on an island, armed with 17 nuclear warheads.

In episode 3, things get complicated because there is already a society on the island, and since the U.S. military has blockaded the island, this society isn’t getting their shipments of supplies. So they kidnap a few of Braugher’s soldiers, give him a deadline to break the blockade and get the supplies through, and then kill one of the soldiers when he misses the deadline.

Here, we get a stark example of how the cycle of violence works: It may have been started by one person (in this case, the U.S. president, although that aspect of the story — investigated stateside by the intrepid Autumn Reeser — is mysterious and will certainly provide surprises down the road), but we can see how it’s difficult to not participate. As a viewer, I was rooting for Braugher to get revenge on those islanders. Interestingly, he basically says, “Fair enough. We missed the deadline, and we paid the price.” This plotline brought out my own hypocrisy: I am rooting for Braugher and his soldiers to get revenge, even though giving them a pass on the murder might be the best path for avoiding prolonged violence and the death of innocents on both sides.

The current story arc on “Star Wars: The Clone Wars” is exploring the notion that the difference between “terrorist” and “freedom fighter” is often a matter of which side you’re on. In a Jedi Council discussion, we learn that the Jedi and the Republic don’t support terrorism, but they do support freedom. So what tactics are allowed when fighting for freedom?

Anakin, Ahsoka and Obi-Wan train some Onderonian rebels in their fight against the Separatists, who control the planet. We’ve seen that Separatists gain territory in two ways: They are either invited by the planet’s government or they occupy the planet by force. In the case of Onderon, it’s the former, but does that make the rebels bad guys instead of good guys? After all, they’re being oppressed by a police state in either case. The tough questions here are muted somewhat by the fact that the Separatists use droids rather than sentients on the battlefield. (Overall, this is a good thing, because I don’t want “Star Wars” to be TOO realistic, but in this case the issue would certainly become more complicated if the rebels were fighting living beings, perhaps even their fellow Onderonians.)

In its epic final-season future war between the fascist Observers and the human Resistance, “Fringe” shows that fighting for one’s freedom is sometimes necessary yet always costly. Etta has no problem torturing a Loyalist for the sake of the greater good, whereas Olivia sympathizes with the Loyalist, whose entire goal in life is to keep his kid safe. Etta tells Olivia that the Loyalist made up the story about his kid to get sympathy, but we as viewers know that’s not the case. So we see that Etta — undeniably a good person — has been driven to do inhuman things and make excuses for her actions.

Overall, though, I don’t have sympathy for people who believe freedom can be traded for safety, so I actually found myself siding with Etta throughout the episode even though her treatment of this specific man is nothing I condone — except when I consider the wider context.

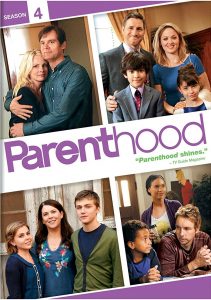

And then there’s “Parenthood’s” fourth season, which has introduced the former East Dillon Lions running back as an Afghanistan war veteran. Things have been kept vague so far, but essentially, he has PTSD and is having trouble re-engaging with everyday, peaceful society. Characters like this are arguably more impactful than anything we see on the aforementioned series that show the battlefield. In a cost-benefit analysis, you can take one look at this kid and realize the cost of war is too high and we must do everything we can to avoid war or — if we’re already involved — avoid escalation of war. I’ve interviewed a few veterans, and while they sometimes agree with the United States’ objectives and achievements, I’ve noticed they always give a quick response when asked if those achievements were worth the price of their friends’ lives: “No.”

War is a complicated issue, of course, but I’m glad four TV shows are actively exploring something the mainstream media rarely touches upon as it gets lost in strategic and political nuances: The true cost of war.