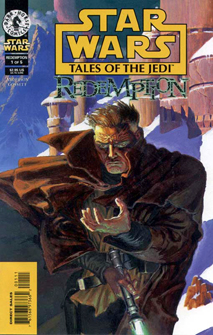

In this “Star Wars” re-reading project, I encounter some stories that are exactly as I remembered them and some that offer pleasant surprises. As I worked through the “Tales of the Jedi” series, I was especially looking forward to the final chapter, “Redemption” (1998), remembering it as being the most emotionally moving “Star Wars” comic book series ever produced.

Unfortunately, I have to file this one under “not as good as I remembered.” “Redemption” is an elegantly simple story, but how much you enjoy it depends on what emotional space you’re in at the time. There’s as much story spread across the five issues of this series as there is in any single issue of the often-overcrammed previous “Tales of the Jedi” arcs. Indeed, writer Kevin J. Anderson and artist Chris Gossett deliberately set out to rectify the flaws of the previous stories — they aimed to pare down the number of characters and let the story — and subsequently, the art — breathe more.

This is probably why I liked it so much on the first reading. There was so much going on leading up to this, but “Redemption” peels a lot of extraneous stuff away and tells a character-driven story. The near-suicidal Ulic Qel-Droma wants to be a hermit (kind of like Yoda and Ben), but he’s not a particularly sympathetic character in the first few issues as he waits to die on the ice world of Rhen Var. He whines a bit about killing his brother, Cay, but mostly he whines about the Force being stripped away from him. (As I get older, apparently I have less sympathy for characters who bring their problems upon themselves. And without a doubt, Ulic did this — much as Anakin chose to kill younglings in “Revenge of the Sith,” Ulic chose to kill revolutionaries and prop up dictators in “Dark Lords of the Sith.”)

In the final issue, when Sylvar attacks Ulic, blaming him for the death of her mate in the Sith War, Ulic drops the “woe is me” attitude and defends himself both physically and logically, telling Sylvar that Crado made his own choices (technically, Crado was under some sort of Sith spell from Exar Kun, but it is accurate that Ulic is mostly free of blame here).

The main thrust of “Redemption” is that Ulic — despite a bit more complaining — trains Vima (Nomi Sunrider’s daughter and Ulic’s would-be stepdaughter if he hadn’t blown it with Nomi by turning evil) as best he can in the Jedi arts. There is one particularly nice little moment: Ulic carves his master, Arca, and Vima carves her father, Andur, out of a wall of ice, Mount Rushmore-style. When Nomi sees the sculpture, she cries, just as Andur melts a bit, forming a “tear.”

Even though a lot of “Redemption” is spent inside characters’ heads, Anderson too often misses the nuances, and characters’ views seem to change too rapidly. Ulic’s return to the living is sparked by Vima’s unwavering belief in him, I suppose, but I wanted more of a big moment to signify that.

It’s hard to argue with the style of “Redemption.” The simplicity of the story may lead to flaws, but it does allow Gossett to time the time to deliver emotional expressions when he draws faces and to vary panel sizes for artistic punch. At one point, Vima and Ulic share a double-page spread; they aren’t talking much, just sizing each other up.

There’s a certain “Star Wars” poetry to “Redemption” — Darth Vader did so many horrible things, but he at least gave the galaxy Luke and Leia; Ulic’s initially well-meaning foray to the dark side was disastrous, but at least he trained Vima in the light side. (This same pattern might be going on currently on “The Clone Wars.” Will Anakin’s Padawan, Ahsoka, perhaps break free of the crumbling Jedi Order and become a behind-the-scenes figure in the formation of the Rebellion, using everything Anakin taught her for the forces of good? If so, she’s another point in Anakin’s redemptive column.)

At least Anderson is somewhat aware of the silliness of Jedi redemption clichés. A Jedi-culture-worshiping spacer named Hoggon shoots Ulic, thinking he’ll get Sylvar’s approval. And indeed, she wanted Ulic dead for his war crimes mere panels prior. During the dialog-laden lightsaber duel, though, Ulic makes Sylvar realize she has to let go of her anger lest she become as bad as he was.

“I guess I’ll never understand Jedi,” Hoggon mumbles.

Really, though, “Tales of the Jedi: Redemption” is all too easy to understand — for all it’s beautiful style, it doesn’t add layers or surprises to an often-told tale.