After an inauspicious beginning under the auspices of Roy Thomas and Howard Chaykin, the “Star Wars” Marvel comics run gets a bump up in quality with issues 11-15, written by Archie Goodwin with art by Carmine Infantino. The gang — or the “star hoppers,” in Marvel parlance — gets back together for a story that may or may not have influenced the 1995 movie “Waterworld.”

Whereas the Aduba-3 arc was as shallow as comic-book plotting can get, this arc on the water world Drexel is more complex and competent. Even as the gang is caught amidst a civil war between pirates (in the sense that they literally live on a pirate ship) and beast-riders, Crimson Jack looms in orbit. While Timothy Zahn gets credit for inventing Interdictor Cruisers — a necessary plot device so ships stand still and fight rather than fleeing into hyperspace — this arc introduces a similar device that pulls ships out of orbit, allowing the pirates to scavenge them.

We get the conclusion to the first legitimate character arc (unless you count Jimm and Effie) in Issue 15, with Crimson Jack’s second-in-command Jolli. Because her father abandoned her, she hates men, and joins Jack’s pirate gang to prove she’s as good as them. Then she develops a crush on Han Solo, and sacrifices herself to save him. Sure, it’s shallow, but it’s a step forward in the series’ character development.

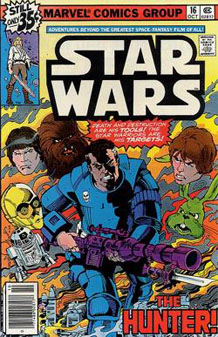

Issue 16, “The Hunter,” is regarded by many as the first really good issue of the Marvel run. Goodwin expands on Thomas’ theory that most of the galaxy is bigoted against droids and cyborgs. The Marvel series — perhaps believing Wuher the bartender’s view to be mainstream — was obsessed with anti-droid bigotry even though it’s not backed up by much other “Star Wars” fiction. Today, we know that the galaxy’s default attitude is that droids are like appliances, and there’s no stigma attached to having mechanical limbs (such as Luke’s hand at the end of “The Empire Strikes Back”).

No doubt “The Hunter” stands out in our memories because of the final panel, where Valance is revealed to be a self-loathing cyborg himself; it’s the kind of twist that a 10-year-old would find cool. Truthfully, the story is a bit silly, not only because Valance wants to kill Luke due to Luke’s appreciation for droids, but also because the bounty hunter has access to Death Star tapes that reveal this information.

Issue 17, “The Crucible,” is also a memorable one because it’s the first pre-“A New Hope” story in the Expanded Universe (the novel “Han Solo at Stars’ End” didn’t come out until 1979). Because the Marvel series up to this point is serialized — in the sense that each issue leads into the next — this story is a flashback that comes about when Luke is daydreaming at the controls of the Falcon.

Co-written by Chris Claremont, it’s similar to Chapter 1 of Brian Daley’s “Star Wars” radio drama in that we meet Luke’s friends and get a T-16 Skyhopper chase between Luke and Biggs through the Jundland Wastes (and Diablo Cut, suggesting that the chase crosses into Mexico for a while). Perhaps Goodwin and Claremont wanted to do justice to Luke’s Tatooine upbringing, something that was given short shrift in the final version of the film (although the famous deleted “Biggs scenes” are in the comic adaptation and the novelization).

Page 4 features a fun continuity gaffe, as the writers (quite understandably) misunderstand Uncle Owen’s relationship with Luke’s dad:

Aunt Beru: “Owen, Biggs is Luke’s best friend. He’ll be gone a year or more. You let a brother leave without saying goodbye. Haven’t you wished –“

Of course, one could argue that Beru is simply using shorthand for “stepbrother.” However, we see in “Episode II” that Owen and Anakin were barely acquainted. Arguably, this is an example of poor prequel writing on George Lucas’ part. Based on the scenes in “Episode IV,” Claremont rightly assumed some sort of shattered bond between brothers. As it stands now, Owen’s desire for Luke to stay on Tatooine reads as selfishness — he just wants a farmhand. It’s hard to argue that Owen is only being protective of Luke — after all, Luke is exposed to danger from Sand People on a daily basis.

In the end, “The Crucible” is a nice little tale that shows Luke’s bittersweet contentment at trading one cadre of friends for another equally worthy group. While it is a filler issue (issue 16 ends with a teaser to issue 18), it reaffirms the teamwork between the Star Warriors, who were split up during the Drexel arc. “Crucible” is wide-eyed “Star Wars” simplicity, but it’s also the best issue of the series up to this point.

The bar will soon be raised, though …