In the ’90s, in almost every lengthy interview in advance of “Episode I,” George Lucas and prequel movie producer Rick McCallum warned that these new movies would not be swashbuckling adventures like the original trilogy. They would be largely political thrillers. It was the most common Lucasian apologia outside of the warning that the films were made for kids.

But actually, political intrigue in “Star Wars” dates back to the very first printed page in the GFFA back in 1976: In the prologue of the “A New Hope” novelization, ghost writer Alan Dean Foster tells readers that Palpatine used his political savvy to rise to the position of emperor. Then Timothy Zahn marked the 1991 “Star Wars” revival with a healthy dose of politics in “Heir to the Empire” — think Borsk Fey’lya.

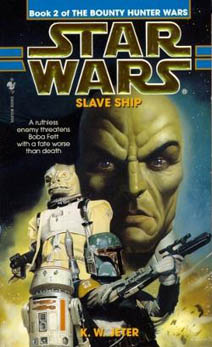

And the best political thriller of all might be K.W. Jeter’s “Bounty Hunter Wars” trilogy, which came out just before Episode I. In the second book, “Slave Ship” (1998), we get to know Kuat of Kuat, who pontificates about how to keep his ship-building corporation wealthy and profitable — and free from takeover by the Emperor or Black Sun leader Xizor. In a highly entertaining sequence, he outsmarts his internal rivals, pulling the plug on a reanimated corpse reminiscent of Captain Pike from “Star Trek.”

(It’s somewhat odd that Jeter didn’t jump at the chance to delve into the droid-brain workings of IG-88 or 4-LOM, considering how much he enjoys wild sci-fi concepts such as the animated corpse here and the half-organic, half-cannon in the first book.)

So concerned is Kuat with a politician taking over his company that he manufactures evidence against Xizor (making it look like he had a hand in the murders of Luke Skywalker’s aunt and uncle), only to worry — now that Xizor is dead — that the fakery will come back to bite him if Palpatine finds out. So often today, we hear about corporations benefitting from big government (and indeed, that’s a serious problem), so it’s interesting to see a businessman plotting to keep big government at arm’s length. (Arguably, that was Palpatine’s biggest strategic flaw: EVERYONE feared him. Had he cultivated more loyal allies rather than aiming to own everyone and everything, the Rebellion might’ve had a tougher time growing and ultimately winning.)

Also in “Slave Ship,” Boba Fett uses his savvy even more so than his cutting-edge technology to outsmart his business rivals. It’s nothing short of delicious to read about him tricking Bossk and Zuckuss. And just like in “The Mandalorian Armor,” this book ends with an embarrassed and angry Bossk cursing Boba Fett from a cramped escape pod.

The title “Slave Ship” has a double meaning: It refers to Fett’s Slave I, of course, but also to Bossk’s Hound’s Tooth, which Fett, Dengar and Neelah have hijacked. That’s in the “now” portion of the story (set during “Return of the Jedi”), which presumably will get more attention in the final installment. In the “then” portion (between Episodes IV and V), Fett has broken the Bounty Hunters Guild into two bickering splinter groups — simply by joining the guild, really. Also during the “then” period, we are privy to entertaining discussions between the Emperor, Vader and Xizor, with the latter two wanting to kill each other the whole time.

Granted, not much galaxy-shaking adventure occurs in “Slave Ship,” nor is there much in the way of character arcs. Still, if you like getting into the heads of sentient creatures, “Slave Ship” is a page-turner just the same.