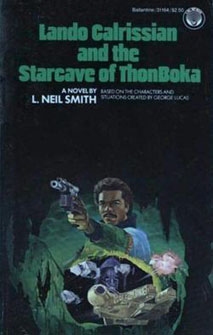

I love “Star Wars” but hate war; it’s a conundrum a lot of fans probably struggle with, and that includes Lando Calrissian trilogy author L. Neil Smith. Getting more specific in this 2006 essay in his web magazine, the Libertarian Enterprise, Smith notes that he loved the first movie and loved the character of Lando, but he also had reservations: “‘Star Wars’ is no more libertarian than ‘Star Trek’ was, or ‘Babylon 5,’ and it’s even more militaristic.”

So how does someone who dislikes the militarism of “Star Wars” tackle it in his final book, December 1983’s “Lando Calrissian and the Starcave of ThonBoka”? He portrays a massive war, of course. It’s not as hypocritical as it sounds, though, because Smith serves up a spot-on, barely-a-parody of big militaries and the way politics determine tactics. The Centrality fleet aims to take out the oswaft — a race of peaceful, ethereal creatures who drift through space.

I certainly concur that the amount of blunt militarism in most “Star Wars” stories, and how that sits with the fact that I still enjoy them, is worth looking into. But the films themselves understand war and politics, much like Smith does in “Starcave of ThonBoka.” In the original trilogy, military strategy is the only way the Rebellion can overthrow the Empire. And in the prequels, before it came to a war of the people against tyranny, we saw that — as Padme laments — “liberty dies, with thunderous applause” if a politician is savvy enough.

In a passage that I think would make George Lucas proud (although I wouldn’t be surprised if he has never read the Lando books), Lando explains the mechanics of Centrality war politics to Vuffi Raa on page 126 of “ThonBoka”:

“There’ll be one group that will loudly — and correctly — proclaim that this undeclared war against the oswaft constitutes genocide, although they wouldn’t hesitate if they’d thought of it first themselves. Then there’ll be a gang of middle-of-the-roaders who could do it better or cheaper. Finally, there’ll be the ones who regard the action as too gentle or indecisive. They’ll want the fleet to sit back and toss in a few planet-wreckers, and they’re probably the ones we owe for this hiatus.”

It’s a timeless summation of how imperialism operates.

I also enjoyed the passages where Lando infiltrates multiple ships of the fleet as it awaits orders, posing as a trader bearing cigars and entertainment. He trusts that the soldiers’ human need to not be bored will trump their discipline, and indeed, he’s playing sabacc with them before long. Perhaps the sequence is a bit over-the-top, but it fits with the tone of this trilogy, always slightly on the humorous side, and with more than its share of moments that a reader just has to shrug off — like when Lando uses the term “Saturday” (there are no days of the week in “Star Wars,” at least not as we know them).

Still, as much as I like “ThonBoka” for what it is, I can’t shake the feeling that the story gets a bit too big, a bit too soon, for our hero. It’s not out of character for Lando to help a creature in need, as he does with a starving oswaft, even up to the point of helping its society to fight off invaders. But does it jibe with the timeline? In “The Empire Strikes Back,” Lando joins the Rebellion only when he’s given no choice; he never had any love for the Empire, certainly, but even Han signed up faster than Lando, and Han had less at stake personally (at least from a standpoint of wealth and property).

Both Han and Lando came from the live-and-let-live school, but the movies showed Lando’s “leave me alone” streak ran a bit stronger. “ThonBoka” kind of contradicts this with the immensity of Lando’s altruistic heroism, although in Smith’s defense, Lando is thrust into various dangers throughout the trilogy, rather than actively choosing them.

What it comes down to, perhaps, is that Smith is a sci-fi writer. I’ve written a lot about the political bent of the Lando books, but there’s just as much science fiction, especially in “ThonBoka,” from the imaginative biology of the oswaft to Vuffi Raa’s struggles to help the good guys kill bad guys even though his programming prevents him from harming living beings. The oswaft are very Clarkean and Vuffi Raa’s internal conflict is very Asimovian.

Sci-fi stories often drift toward big set pieces as a way to give the ideas more punch, and it’s understandable that Smith would want to go out with a bang — even when writing it, he probably knew this would be his last “Star Wars” book, as he wasn’t thrilled with Lucasfilm’s tight deadlines.

But I feel like a more personal, less epic, military-free Lando origin story needs to be told somewhere down the road.