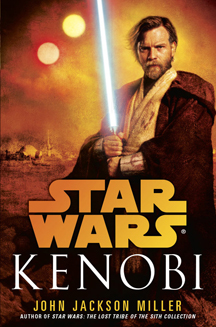

While it’s often been noted that “Star Wars” has elements of Westerns, “Kenobi” (August 2013) is the first novel to fully embrace the genre. John Jackson Miller, who between this and “Lost Tribe of the Sith: The Collected Stories,” has earned a spot on my short list of elite “Star Wars” authors, finds the perfect subject for a full-on Western in a Galaxy Far, Far Away: Ben Kenobi’s time after he settles on Tatooine to watch over Luke.

As Miller notes in the acknowledgements, much had been written about life on Tatooine, but less so about Kenobi’s time there. Miller makes excellent use of the topography, economy, government, flora and fauna of the desert planet that had been explored in reference works such as Starlog’s Tatooine Technical Journal and Kevin J. Anderson’s “Illustrated Star Wars Universe,” and works of fiction ranging from “Episode I” to “Tatooine Ghost.”

Miller soaks up all the pertinent works regarding the planet and smoothly works them into this narrative, where a reader learns even more about, for instance, the culture of the Sand People. He nicely retcons Anderson’s assertions that Tusken Raiders’ genders are unknown with the different garb for women shown in “Attack of the Clones.” Indeed, the Tusken leader in “Kenobi” wears the classic attire first seen in “A New Hope,” but she is female.

Miller also works in the tale, chronicled in the “Star Wars: Republic” comic series, of A’Sharad Hett, a Jedi who becomes a Tusken Raider. And most cool of all – since I had recently re-read the Marvel comics – he gives Mosep Binneed a significant part to play. Mosep is Jabba the Hutt’s Nimbanel accountant who also sometimes pretends to be Jabba on various galactic errands. This is a retcon for the original design for Jabba as seen in Issues 2 and 27 of the Marvel comics. It doesn’t totally work, because it doesn’t explain why Han thinks Binneed is Jabba in those comics (Han had met the real Jabba in the “Han Solo Trilogy”), but still, I love it when authors give a fair attempt at smoothing out this grand narrative.

But those are merely neat little touches. It’s the Western-ness that seeps into every one of these pages that makes “Kenobi” a classic. The titular hero is a Shane-like loner who is settling into an abandoned hut on the edge of the Jundland Wastes, intent on a strange combination of forgetting and atoning for his past. But, no matter how intent one is on being a hermit, sentient interaction is inevitable, so he often finds himself shopping for supplies at Danner’s Claim. It’s essentially a bustling truck stop in the desert, and it allows us to meet the book’s other main characters, Annileen Calwell and her two children and Orrin Gault and his two children. Colorful regulars abound at the Claim, too.

The Calwells and Gaults are mixed up financially and romantically, and it leads to lots of juicy drama, with a touch of humor with the way Ben keeps getting into the middle of it despite his best efforts. I also like the hint of a romance between Ben (who has shed the name Obi-Wan for undercover purposes) and Annileen, as well as the ironic fact that everyone calls her “Annie.”

Much like “Darth Plagueis” in 2012, “Kenobi” was the must-read “Star Wars” novel of 2013. Miller respects Ben’s adventures from previous yarns, including his relationship with Satine in “The Clone Wars,” and he addresses some continuity oddities; he explains the rapid aging process caused by Tatooine’s twin suns and the reason why Ben’s last name leaks out. Yet for all those grand Jedi adventures out there and the fact that he started Luke on his path, it’s “Kenobi” – elevated by its deliciously melancholy and rural Western vibe – that stands out as the essential yarn for understanding this major “Star Wars” character.