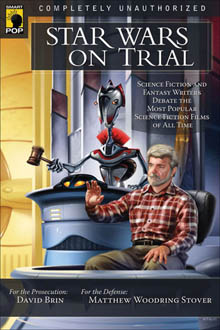

Here is the third installment of my series inspired by Benbella Books’ “Star Wars on Trial” (2006), a collection of essays responding to eight charges against the “Star Wars” franchise. Sci-fi author David Brin, a critic of the prequels, was the prosecutor, and Matthew Stover, author of four “Star Wars” novels, represented the defense. Various essayists were the witnesses for each side …

CHARGE NO. 7: WOMEN OF STAR WARS ARE PORTRAYED AS FUNDAMENTALLY WEAK.

Out of the eight charges in “Star Wars on Trial,” this is the one I found most stupid on the surface. The iconic imagery immediately flashes through my head in defense of the charge: Leia grabbing Luke’s blaster and leading the escape into the garbage chute, or strangling Jabba with her slave chains. Padme leading the infiltration of Theed Palace, or climbing atop the tower in the execution arena and blasting her Geonosian captors.

But it also features the best Prosecution essay in the book, one that almost changed my mind and had me declaring “Star Wars” guilty as charged. Jeanne Cavelos, who was a teenager in 1977, used to gaze at her “A New Hope” poster — the one where Luke holds his lightsaber high and Leia wields a blaster — and imagine Leia as a brave freedom fighter. Cavelos breaks down the original trilogy in depth, and – the aforementioned iconic scenes notwithstanding – finds many examples where Leia’s characterization plays second fiddle to Luke and Han (for example, she stands around an worrying on Yavin IV while Luke and Han do the fighting, and doesn’t show much of a reaction on Endor when she learns Darth Vader is her dad). Then the essayist does the same with Padme (for example, Padme looks to Anakin – of all people! — for guidance in “Episode III,” completing the role reversal from “Episode I,” where she was a generally ineffective wartime leader).

Cavelos also picks away at another ingrained notion. Back during “Buffy’s” days as a groundbreaking show, I – and other writers penning shallow treatises – would say Buffy Summers follows in the tradition of Princess Leia, “Alien’s” Ellen Ripley and “Terminator’s” Sarah Connor, without giving it much thought. Cavelos notes that the 1970s TV characters Wonder Woman and Bionic Woman are too often overlooked, and additionally rightly observes that Ripley and Sarah come from the horror tradition where the woman is the damsel in distress (in fact, so does Buffy). It wasn’t until the second films of the “Alien” and “Terminator” franchises that Ripley and Sarah became action heroes. If Leia had an impact on Ripley and Sarah, it wasn’t as immediate as our memories tell us.

Still, I think there is somewhat of a through-line there. Leia was shooting stormtroopers side by side with the boys before Ripley mowed down aliens with the colonial marines and Sarah Connor took on a T-1000 alongside a friendly Terminator. Both Ripley and Sarah were protecting kids at the same time, showing their mothering side, something Leia wasn’t saddled with, and Sarah and Buffy each had the pressure of defending the entire world. Those are examples of each female action hero taking on a bit more than her predecessors. Among film and TV icons, the trend can be traced back to Leia, even if we can’t say for sure that she influenced them.

Bill Spangler provides an admirable essay for the Defense, basically putting a positive spin on Leia’s traits that Cavelos sees as negative, and also pointing out Mon Mothma’s role as a Rebellion leader and EU examples such as Yaddle’s heroism in a kids’ novel.

But Cavelos and Spangler wrote those essays in 2006. Now it’s 2014, with six seasons of “The Clone Wars” behind us, and I don’t have to stretch at all for a rebuttal. In fact, the creation of Ahsoka Tano by George Lucas, Dave Filoni and Henry Gilroy as the audience surrogate in “The Clone Wars” could’ve been a direct response to Cavelos’ essay, or it could’ve been in response to those writers’ concerns that girls weren’t getting as many “Star Wars” role models as boys. (The imbalance of male to female characters in “Star Wars” is no great secret. If that was the charge, I’d have to return a guilty verdict.) While “The Clone Wars” has three main characters, Ahsoka trumps the other two because we know the fates of Anakin and Obi-Wan. (Unfortunately, we may never learn Ahsoka’s fate, but that’s another issue).

Not that Leia or Padme are failures as characters. Leia goes on to be a very good leader of the New Republic in the Expanded Universe novels, raises three kids and eventually starts her Jedi training. And as the “Revenge of the Sith” novelization tells us, Padme played an essential role in forming the Rebellion (along with a young Mon Mothma). But Ahsoka filled a void in the “Star Wars” mythos that I didn’t realize was missing until I met her – a fully fleshed-out female character who will never be accused of being “fundamentally weak.”

More “Star Wars on Trial” essays: (Part 1) (Part 2) (Part 4)