Dark Horse’s various “Boba Fett” comics from 1995-2006, although heavy on style more so than character development, nicely illustrate the mysterious and dispassionate Boba Fett we knew and loved from his five-line appearance in “The Empire Strikes Back.”

Starting in 2002, the mystery began to be cleared up with young Boba’s origin story as a clone of Jango Fett in “Attack of the Clones,” and further yarns began to explore a passionate Fett at both ends of his timeline. In “The Clone Wars,” young Boba seeks revenge against Mace Windu for killing his dad. And well into the New Republic era, in Karen Traviss’ “Legacy of the Force” books, Fett becomes a family man (he even has a granddaughter) and connects with his planet and culture (Mandalore and Mandalorians). Furthermore, the “Blood Ties” comics explore Boba’s bond with other Jango clones.

But during the Rebellion era – from a bit before “A New Hope” to a bit after “Return of the Jedi” — Fett is dispassionate and cool. In books, this incarnation of Fett was explored in the “Tales of the Bounty Hunters,” “Tales from Jabba’s Palace” and “The Bounty Hunter Wars” trilogy. Comics offered up the biggest smorgasbord of vintage Fett tales touching on so-universal-they-are-cliches reasons we loved the character from “The Empire Strikes Back”: 1) Even Darth Vader respects him, 2) He has his own moral code, 3) He’s good at what he does and he looks good doing it, and 4) He’s a mysterious loner.

(For the purposes of this essay, I’m looking at the seven “Boba Fett” standalones, the four-issue “Boba Fett: Enemy of the Empire,” and the two issues of “Empire” that are essentially Boba Fett standalones – and were indeed collected in “Boba Fett: Man with a Mission.”)

EVEN DARTH VADER RESPECTS HIM

Vader treats Fett as an equal to be respected more so than a tool throughout “Empire.” For example, Vader tells Lando “I’m altering the deal. Pray I don’t alter it further.” By contrast, he tells Fett “The Empire will compensate you if (Han Solo) dies” and allows him to take the carbon-frozen Solo to Jabba the Hutt. Vader clearly values Fett enough to work with him rather than brushing him aside or killing him.

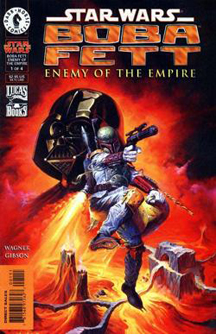

A lot of fans speculated that this was because Vader and Fett went way back. Some thought Kitster, Anakin’s buddy in “The Phantom Menace,” would grow up to be Fett. Somewhat oddly, as it turned out, Anakin and Fett never meet in the prequels (even though they are the only main characters to get origin stories dating back to their childhoods) or “The Clone Wars” (even though both are prominently featured). As such, 1999’s “Enemy of the Empire,” set just before “A New Hope,” avoided becoming an apocryphal story of the pair’s first meeting.

As the story begins, Vader does not respect nor understand Fett, whom he has hired to track down a valuable item for him: “The bounty hunter … can be relied upon to disobey me,” Vader thinks, unaware that Fett always honors his contracts (unlike Vader himself, who sends goons out to trail Fett, and plans on killing the bounty hunter after he gets the goods). Fett fights him to a draw in the final issue, and we can assume this is the moment when Vader gains respect for Fett.

HE HAS HIS OWN MORAL CODE

That’s not to say that Fett’s a good guy, but rather that he’s a different type of bad guy. He’s as easy to understand as the rules of “Fight Club”: 1) He always looks out for himself, and 2) He always looks out for himself. At the end of “Enemy of the Empire,” Fett has a shot at killing Vader, but he passes, thinking the act “may have brought the whole Empire down upon his head.”

As a freelance bounty hunter, Fett is a superb businessman. His first goal is staying alive, as the above example shows. The next most important thing to Fett and his career is reputation. In “Twin Engines of Destruction” (1995-96, first printed in Star Wars Galaxy Magazine Issues 5-8), Fett tracks down and kills Jodo Kast, who has been passing himself off as Boba Fett in order to get bigger bounties. There’s no money in this self-assigned mission, but it’s important that Fett eliminate Kast so that people don’t confuse this lesser hunter with Fett and so people don’t think Fett is weak for allowing a cheap knockoff to operate. Just as Fett doesn’t need his contracts to be backed by a third party (he eschews the Bounty Hunter’s Guild in “The Bounty Hunter Wars,” for example), he enforces copyright law with his wrist-mounted blaster, too.

More examples of Fett operating with his reputation in mind are:

- In “Wreckage” (“Empire” Issue 28, from 2004), Fett kills an Imperial who is unable to complete his payment. Although the man promises discretion if Fett lets him off the hook, Fett can’t risk word getting out that he allows deals to be broken.

- In “Agent of Doom” (2000), a client offers Fett 100 credits. Fett pulls a blaster on him and says “You know who you mock?” The client points out that Fett’s reputation has taken a hit since word got out that he was eaten by the Sarlacc and Han Solo escaped him. So Fett takes the job as an opportunity to restore his reputation.

One reason fans sometimes see Fett as less evil than Vader is that he’s interested in money more so than power. While money can buy power, it can also buy the freedom to keep flying, and the latter interests Fett more. In “Overkill,” Fett asks an Imperial commander why he wiped out a successful local factory rather than taking it over:

Imperial: “I’m thinking bigger. … Power will be more important than wealth.”

Fett: “I’d have taken the credits. A lot of enemies come along with that power you’ve just inherited.”

The man gulps, realizing Fett has a point.

Fett’s interest in reputation and money more so than power doesn’t mean he is less prone to kill people than Vader is (although, obviously, Vader has racked up a higher death count), it means he does so only if there’s profit in it. He will also choose not to kill if that’s the best monetary move. If a target can supply Fett with more money than he was paid to kill the guy, he’ll sometimes take the new deal, as he does in “Overkill.” However, it seems he’ll only make the new deal so long as he can also honor the original deal, or at least be confident that no one will know he fibbed on the original deal.

Fett isn’t a political man. He’s an anarchist for pragmatic reasons, not because of beliefs in peace or liberty. In “Twin Engines of Destruction,” he notes that he’ll take jobs from the Rebellion, but he prefers taking jobs from the Empire. This is no doubt because 1) The Empire pays better, and 2) The Empire is in power at the moment, and it’s safer to have power on his side.

Really, when we throw around the phrase “moral code” in regards to Fett, what we really mean is that he looks out for No. 1, he’s not stupid and he’s not a hypocrite. Those traits make him stand out among “Star Wars” villains.

HE’S GOOD AT WHAT HE DOES AND HE LOOKS GOOD DOING IT

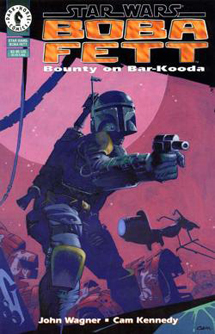

Although other writers and artists contributed to the “Boba Fett” comics, the most iconic issues came from writer John Wagner and artist Cam Kennedy. They collaborated on four issues (1995’s “Bounty on Bar-Kooda,” 1996’s “When the Fat Lady Swings,” 1997’s “Murder Most Foul” and 2003’s “Sacrifice,” which is “Empire” Issue 7), and each of them contributed to additional titles (Wagner on “Enemy of the Empire” and 1997’s Wizard special issue “Salvage” and Kennedy on “Agent of Doom”).

Wagner, who also wrote about Fett in “Shadows of the Empire,” has a dark, deadpan sense of pathos that comes from showing the master bounty hunter doing his job methodically and dispassionately. For example, it’s worth a wry chuckle when Fett helps a noble rebellion in “Sacrifice,” not because he cares about the rebellion, but because he’s adhering to his moral code: His client didn’t pay him the agreed price, so Fett walks out amid the conflict. Other writers took Wagner’s cue: In John Ostrander’s “Agent of Doom,” Fett frees some innocents because it’s part of his assignment, but when they ask him what they should do now that they’re out of their cages, Fett says:

“Not my concern. Survive. Take the planet. Call for help. Up to you. My name is Boba Fett. Remember that.”

The writing throughout the “Boba Fett” titles is reminiscent of Jim Woodring’s on the “Jabba the Hutt” comics, but those scripts were paired with cartoony art, leading to a dark brand of laugh-out-loud humor. Despite some over-the-top characters such as the vengeful beast Ry-Kooda, who is all jaw and teeth, “Boba Fett” delivers a less-humorous type of dark humor, and the difference in tone is thanks to Kennedy’s watercolor palette of blacks, browns, blues and greens, which can also be seen in the “Dark Empire” series. It’s the perfect style for showing Fett doing his thing.

HE’S A MYSTERIOUS LONER

Dengar nurses the post-Sarlaac Fett back to health in the “Bounty Hunter Wars” books, and he tags along with the still-healing Fett on the Kast mission in “Twin Engines of Destruction.” But at no point in either the books or the comic do we feel like Fett considers Dengar a friend, which is a real accomplishment by the authors in preserving this dispassionate Fett portrayal.

I suppose it goes back to the Western trope of the mysterious loner, only it’s taken to the nth degree with Fett because he wears his Mandalorian garb all the time. He’s not merely a loner in terms of relationships, he’s a loner to nature itself, as he won’t let a breeze touch his face. Although “Twin Engines” intriguingly shows us a bandaged-up, out-of-his-armor Fett (he looks like the Invisible Man, appropriately), what he actually looks like remains a mystery. With his helmet firmly in place, he tells Dengar: “THIS is my face.”

While the first three factors in what makes Fett cool still hold up post-2002, it’s the stripping away of the “mysterious loner” archetype that has pushed Fett’s portrayal from dispassionate to passionate. The revelation of Fett’s face and backstory was inevitably a catch-22: Fans longed for it, but it irrevocably changed his character – temporarily for the worse, as we met him as a kid essentially making “pew-pew” blaster noises while riding shotgun in Slave I. Traviss helped make Fett interesting again by showing him mellow with age and connect with Jango’s heritage in “Legacy of the Force.”

Then “The Clone Wars” began to show Boba’s transition from angry kid to dispassionate bounty hunter. Teenage Fett was learning tools of the trade from Aurra Sing and working with Bossk and Dengar at the time the show was canceled. Although “Rebels” will likely feature Fett at some point, it takes place around the time of “Enemy of the Empire,” when Fett is an adult who already has a reputation as an elite bounty hunter.

This is not a defense of “The Clone Wars’ ” cancellation by any means, but it did allow the first big transition period in Fett’s life remain mysterious just when the veil was about to be pulled back.