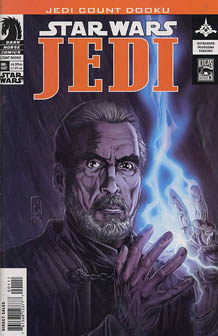

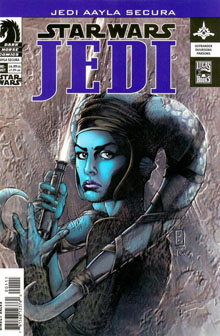

Most of Dark Horse’s Clone Wars campaign was fought in the pages of “Republic,” but a notable exception is the five-issue “Jedi” series — 2003’s “Mace Windu,” “Shaak Ti,” “Aayla Secura” and “Count Dooku” and 2004’s “Yoda.” These double-length issues were part of the ongoing “Republic” continuity, but they also focused more deeply on an individual Jedi (or in Dooku’s case, fallen Jedi).

John Ostrander (assisted by gorgeous Jan Duursema pencils that are the pinnacle of Dark Horse “Star Wars” art) writes four of the five issues, and “Count Dooku” is the masterpiece of the bunch. Even though it tells the familiar story of an undercover Jedi’s fall to the dark side (see also Luke in “Dark Empire” and Ulic Qel-Droma in “Tales of the Jedi”), I was thoroughly engaged by the twists and turns before Quinlan Vos ultimately bows to the sway of the evil Dooku. Ostrander peppers in previous events so nicely that I assume he had been building up to this story since before Dooku was announced as the “Episode II” villain. We learn that the Guardian of the Kiffar, Sheyf Tinte, had set up Quinlan’s parents to be killed by the Anzati (“Darkness,” “Republic” 32-35) so she could groom Quin as her successor.

Dooku plays Quinlan even more masterfully than Sidious will play Anakin in “Episode III” – after all, Anakin came very close to siding with Mace Windu in that pivotal moment. But Dooku is always a safe step ahead of our hero. First, he forces Quinlan to blow his cover by threatening Sheyf Tinte. “I’ve known the truth about you from the start, Quinlan Vos,” Dooku says. Then Dooku, saying “I only need to open your eyes,” tells Quinlan of Tinte’s betrayal, and he turns Quin from an undercover agent into a true minion. Or does he? The mystery of Quin’s loyalty – the best storyline from Dark Horse’s “Republic” saga — will continue to play out.

“Aayla Secura” starts with Aayla learning that her former Master is infiltrating the Separatists, but while Ostrander includes many flashbacks to his previous Aayla-and-Quin stories, this is ultimately a solo Aayla story. For the first time in the Clone Wars era, we catch up with the ex-Jedi bounty hunter Aurra Sing, who is presented as a foil to Aayla. Whereas Aayla overcame the influence of an Anzati dark Jedi back in “Darkness,” we learn that Aurra’s antenna was implanted by her Anzati captors (as seen in the short comic story “Aurra’s Song”). It allows her to soak up the glorious fear of her opponents in the style of an Anzati proboscis.

Surprisingly, we learn that the Dark Woman did indeed abandon her student. I had assumed that was merely Aurra’s spin on the situation when she told it in “Aurra’s Song.”

Dark Woman (to fellow Jedi Master Tholme): “We never really connected. When Aurra was kidnapped by star pirates on that trip to Ord Namur, I decided to let her go. It was the will of the Force, I told myself. How many Jedi have died since because of my harshness, my hardness of heart? How many more will die?”

“Mace Windu” does the important work of outlining the reasons we should side with the Republic rather than the Separatists. The films’ main reasoning is that Dooku is a Sith Lord, and while that’s a good reason, it’s also simplistic. In this yarn, Mace meets with five dissident Jedi – including future Dooku minion Sora Bulq, a Weequay — who did not heed Yoda’s call to return to Coruscant to claim generalships in the Republic army. Their reasons range from pacifism to a suspicion that the Separatists have the moral high ground. But because Mace does not serve up a “join us or die” ultimatum, I respect him as a representative of the true ideals of the Jedi (and the Republic, in theory, although we as “Star Wars” fans are privy to omniscient knowledge about what Sidious is doing).

A companion piece to “Mace Windu” is the issue featuring the only Jedi who is even more revered. Penned by Jeremy Barlow (who would go on to write many “Clone Wars Adventures,” “Empire,” “Rebellion” and “Knights of the Old Republic” comics), “Yoda” features manga-esque art by HOON, and Japanese influences such as a metaphor-laden flower garden. It fits nicely with the old Jedi Master, as a reader might draw a parallel to Mr. Miyagi from “The Karate Kid.” Yoda travels to talk with an old friend, the leader of the planet Thustra, who has sided with the Separatists. Yoda reserves violence only as the very last resort (and even then, only in self-defense). This story’s young Padawan fails to heed Yoda’s lessons.

Cal: “There you are! I’ve been waiting for hours!”

Yoda: “And in that time, patience you still have not learned.”

Perhaps Yoda will fare better with his young charges in the novel “Yoda: Dark Rendezvous.”

Ostrander’s “Shaak Ti” is the weakest of the five “Jedi” issues – but hey, at least it guest-stars Quinlan Vos. Shaak’s trait of honesty is emphasized when she agrees to free a criminal she had put behind bars in exchange for her help. But that fairly common Jedi trait doesn’t set Shaak apart, and she never became a major character on par with the other four “Jedi” characters. (On the other hand, Shaak does have an interesting behind-the-scenes story. She was killed by General Grievous in an “Episode III” deleted scene, but because that scene was cut, she later emerged in “The Force Unleashed” as one of the few Jedi to survive Order 66.) I wonder if Ahsoka Tano was Lucasfilm’s fresh attempt to launch a popular female Togruta Jedi where Shaak Ti had fallen short.

It’s too bad that “Jedi” was canceled after five issues (although it should be noted that a proposed sixth issue, “Barriss Offee,” was adapted into Ostrander’s “Show of Force” in “Republic” 65-66). I like the way these issues are forced – by way of their titles – to zero in on the traits of a specific Jedi. Heck, considering all the Jedi in the Geonosian arena, this series could’ve lasted 30 issues.