As a kid, I imagined the Jedi Purge consisted of Darth Vader going from planet to planet slaughtering Jedi Knights. That’s what naturally springs to mind when we hear Obi-Wan’s line: “A young Jedi named Darth Vader, who was a pupil of mine until he turned to evil, helped the Empire hunt down and destroy the Jedi Knights.” (In retrospect, it’s kind of disturbing that a kid would dream up visions of mass murder in piecing together the backstory of his favorite movie, but that’s beside the point here.)

“Episode III’s” Order 66 simplified the Jedi Purge: Responding to an implanted brain-trigger, the clones take the Jedi by surprise, killing them before they know what’s happening. However, the old idea of Vader “hunting down” the Jedi still had a lot of appeal, partly because of Obi-Wan’s dialogue (even though many of his lines in “A New Hope” were revealed as fibs in light of the prequels) and partly because it’s common sense: Obi-Wan and Yoda escaped, and because it’s a big galaxy, it follows that some other Jedi escaped as well. It’s basic math.

It’s not just a Legends concept. The earliest Disney canon stories – the novel “A New Dawn” and the TV show “Rebels” – feature as a main character the Jedi Kanan (OK, he’s a Jedi-who-never-was, but he’s in the ballpark). Ahsoka’s survival is also official canon, to say nothing of Ezra, Luke and Leia. But Legends has absolutely adored the concept of “the last Jedi”: Just off the top of my head, there’s Jax Pavan, Dass Jennir, Kyle Katarn, Starkiller, Shaak Ti and Maris Brood.

There are also dark-side survivors, including the Inquisitor from “Rebels” in the Disney canon. As for the EU, in the “Rebellion” arc “The Ahakista Gambit,” we learn that the dark-sider Sardoth helped in the Jedi Purge before the Emperor attempted to purge all the dark-siders as well.

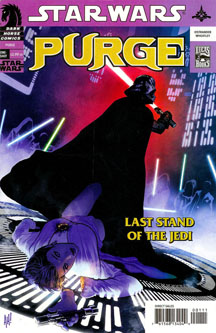

Naturally, Dark Horse couldn’t resist putting out some “Purge” comics to truly delve into what Obi-Wan was talking about: the non-subtitled “Purge” (2005), “Seconds to Die” (2009), “The Hidden Blade” (2010) and the two-issue “The Tyrant’s Fist” (2012-13). The five issues were collected in a July 2013 trade paperback.

The “Purge” comics suggest that Obi-Wan’s quote is slightly off. Like a man with obsessive-compulsive disorder, Vader can’t know peace until he kills every last Jedi in the galaxy. But the Emperor himself hardly cares that there a few scattered Jedi out there, and he’s ticked off that Vader can’t leave well enough alone. Vader kills eight Jedi in the 2005 “Purge” one-shot, and Palpatine uses the incident to spread rumors that Vader killed 50 Jedi. Vader is a blunt instrument; the Emperor is a schemer, and he’ll find a use for his tool even when it malfunctions.

Written by John Ostrander of “Republic” fame and drawn by Doug Wheatley of “Dark Times” fame, this first “Purge” one-shot has crossover appeal as we catch up with Jedis Tsui Choi, who had appeared in several “Republic” issues, and Bultar Swan, who is on screen in “Episode II.”

“Seconds to Die,” also by Ostrander, is a clever style piece where Sha Koon, niece of Plo Koon, believes she is the last Jedi and must therefore try to kill Vader in the tunnels below the Jedi Temple. Ostrander shows that while the “Purge” template of Vader killing a Jedi straggler is hard to overcome, it doesn’t mean he can’t wheedle a happy ending out of it.

In Haden Blackman’s “The Hidden Blade,” the Emperor gives Vader the mission of overseeing production of AT-AT walkers. But he tempts his apprentice with the idea of a rogue Jedi on the planet, and when Vader takes the bait, Palpatine strands Vader there. (The cliffhanger isn’t resolved, but his presence in future stories makes it clear Vader got off-planet somehow.) Similar to “Darth Vader and the Ninth Assassin,” the Emperor’s scheme doesn’t really hold together if you think too hard about it.

The “Purge” series wraps with its best story, despite coming from newcomer Alexander Freed, who would go on to write some “Old Republic” comics and Star Wars Insider short stories. Because it has two issues to work with, “The Tyrant’s Fist” tells a deeper story about how the Empire purges not just the Jedi as people but also the Jedi as an idea. This is an important theme to tackle, because by the time of the classic trilogy a mere 20 years down the road, the Jedi and the Force have become ancient religions to John Q. Public (as personified by Han Solo).

When we watched “A New Hope” as kids, we subconsciously figured the Jedi Purge happened, say, 40 years ago, and the passage of time explains the knowledge gap. When the timeline got tightened to the official 20 years (which, in retrospect, is necessary, due to the ages of Luke and Leia), it made Freed’s story essential.

In the ironically titled “The Tyrant’s Fist,” Vader has begun to learn lessons from his master. Rather than merely murdering the last Jedi on Vaklin – a planet that has long revered Jedi – Vader embarrasses him by exposing him to a toxin that makes him act foolish in public. Just as crucially, the Empire builds schools and offers citizens jobs.

At the start of the tale, the local Imperials doubt they can crush the insurgency; by the end, half of the people are enthusiastic about the Empire, half are waiting to see what happens. It’s the way governments have gained power throughout history. As long as most people don’t figure out that the government’s wealth came from the people, and thus left them poorer, a government will always be seen as an entity that’s looking out for the good of the downtrodden. (Oh, and the Empire also executes the most outspoken resistors. That helps speed things along.)

The sly purging of political ideas other than “Imperial might makes right” in “The Tyrant’s Fist” repurposes the Jedi Purge as something even scarier than Vader committing mass murder.