The seventh “Rocky” film, “Creed” — which comes out on Nov. 25 – is on paper quite a departure from the first six, which were all written by Sylvester Stallone and directed by Stallone or John G. Avildsen (the first and fifth entries). And most obviously, those films told Rocky Balboa’s life story, whereas in “Creed” Rocky will be a side character and Adonis Creed (Michael B. Jordan), the son of Apollo, will take the spotlight.

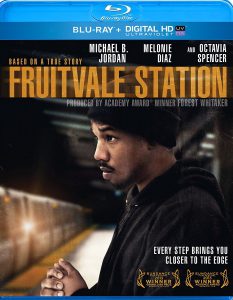

There doesn’t seem to be much apprehension about the change in leadership of this beloved franchise, and there’s a good reason for that, which can be traced back to 2013’s “Fruitvale Station,” written and directed by Ryan Coogler and starring Jordan. Coogler’s lump-in-your-throat debut movie about the last day in the life of Oscar Grant III, who was killed by a Bay Area Rapid Transit police officer on Jan. 1, 2009, no doubt earned him the writing and directing gig on “Creed,” which is co-written by Aaron Covington.

Jordan is comparatively a veteran, although “Creed” will mark his highest-profile film role. He burst onto the scene on “The Wire,” then gained more mainstream attention in two Jason Katims shows — as the troubled East Dillon quarterback on “Friday Night Lights” and Haddie’s boyfriend on “Parenthood.” “Fruitvale Station” just cinched the notion that he’ll be great in “Creed.” He often plays imperfect characters (aside from Haddie’s idealized food-pantry-working boyfriend, perhaps), but he always makes a viewer root for them.

Although differing in the truism of the story (“Fruitvale” is based on real events, “Rocky” is not), “Fruitvale” has a lot in common with the original “Rocky.” The lower economic class neighborhoods of North Philadelphia in 1975 and Oakland in 2008 are nearly identical, and the characters would recognize each other’s circumstances, except that Grant had more family support. Like Rocky, Grant was by all accounts (including the film’s) a good-hearted guy who found time to help strangers and animals. In “Fruitvale,” Grant helps a stranger choose the right fish for a fish fry, and tries to rescue a dog hit by a car. Both also have a darker, desperate side: Rocky is a loan-shark collector, and Grant had spent some time in prison, presumably for something relating to drugs.

Watched back to back (I’m watching the “Rocky” DVDs for my blog, while “Fruitvale” happened to be on Showtime), the two indie films shine a light on the role of random chance in life. Rocky essentially wins the lottery when Apollo Creed chooses him as his bicentennial fight opponent, something that comes with a $150,000 payday. Grant was the recipient of the opposite of the lottery when he was senselessly shot to death in a subway tunnel. (To add insult to injury, his killer spent less than a year in prison for involuntary manslaughter, despite cellphone camera footage showing the crime; this was the first high-profile case of a police killing caught on video).

The major difference between the narratives is that “Rocky” has a traditional structure where we follow Rocky from small-time fights where the crowd shouts “Bum!,” through his lucky break, through training, through the final bout. “Fruitvale” is a series of vignettes, which works perfectly for the story of a life cut short.

Coogler will of course use a more traditional plot structure in his “Rocky” franchise debut, but the idea that “Creed” could have a bit of “Fruitvale’s” vignette flavor is delicious to think about. Perhaps the best scene in “Rocky” is when Rocky goes off on a rant rejecting Mickey’s offer to train him. Stallone improvised the scene, and both he and Burgess Meredith embody deeper stories that go beyond the dialogue: Rocky wonders where Mickey was when he really needed help; Mickey is desperate for another shot at glory.

As the “Rocky” franchise went on, it gradually embraced its cartoony side with more farfetched scenarios for putting Rocky in major bouts, followed by highly stylized portrayals of those prizefights. While 2006’s “Rocky Balboa” was a return to the series’ gritty roots, “Creed” could double down on that with the touch of Coogler and Jordan.

In the end, of course, the difference between “Fruitvale” and “Creed” will be the sense of hope. While it’s a well-crafted and important film, “Fruitvale” has a bit of a “doing your homework” feel to it, as you know you’ll feel angry and frustrated by how it ends. “Creed” – whether Adonis wins his bout or merely proves something to himself — will be a story of life, rather than death. The sobbing at “Fruitvale” screenings might be replaced with cheers at “Creed.”