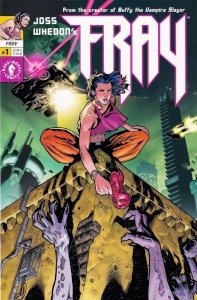

While most of the Dark Horse “Buffy” comics released during the show’s TV run are considered non- or quasi-canonical – and are rarely talked about by fans — a glowing exception is the eight-issue “Fray” (June 2001-July 2003). Written by Joss Whedon when he had free moments while overseeing three TV shows, it’s the complete origin story of Melaka Fray, a Slayer called to duty in the 23rd century, long after Slayers and magic have been forgotten by the populace. Demons and vampires – called “lurks” – can be found in the slums, but no one knows their historical significance.

Taking place in the evocative futuristic/post-apocalyptic cityscape of Haddyn (presumably somewhere in what used to be the USA), “Fray” – gorgeously brought to life by Karl Moline (pencils), Andy Owens (inks) and Dave Stewart (colors) — stands as a goal line as we read the “Buffy” Season 8-and-beyond comics (which are still going today). We wonder if we’ll encounter anything that links up. The first connection actually came in “Buffy” Season 7 (2002-03), when Buffy wields the same scythe that Melaka receives from her pseudo-Watcher, the demon Urkonn, in Issue 6 (March 2002).

That’s a cool continuity touch, but “Fray” also raises deeper questions of how it all ties together. For instance, there is no magic in Fray’s world. In Season 8, the Seed is destroyed, erasing magic from Earth, and leading us to suspect that might be a link to “Fray.” But then magic is restored to the world in Season 9, so apparently it’s not a link. In Fray’s time, there are no Slayers – or more specifically, no Slayer knows they are a Slayer. This wildly contrasts with the Buffy Summers era, when there are thousands of Slayers – as per Buffy’s and Willow’s action at the end of the TV series — and the fact of Slayers’ existence is known by the populace.

Urkonn seeks out Melaka because The Slayer is needed again. Mel’s twin brother, the vampire Harth, aims to open a portal to a demon dimension, something that smacks heavily of “Angel’s” TV finale and the subsequent “After the Fall” comics from IDW.

Against this backdrop of familiar beats, Whedon does his usual undermining of clichés, but what’s interesting about “Fray” is that he subverts his own Buffyverse clichés. Although Fray gets Slayer strength, Harth – due to a twin glitch the Powers That Be hadn’t planned for — had gotten the Slayer dreams. So Melaka lacks historical perspective. This is at the heart of why it’s hard for Urkonn to communicate why she must follow her destiny. (The massive and fierce-looking demon being frustrated by this skinny girl and her narrow worldview is a major source of the comic’s comedy.) Furthermore: While it certainly seems like Urkonn is the Giles to Fray’s Buffy, is he really? Or is he hiding something?

A reader could draw broad parallels between Melaka and Faith. Melaka is a thief – or “grabber” – for an aquatic crime boss named Gunther, whose home office is a tank of water. She is also extremely poor, living in such squalor that her apartment (where she is probably squatting rather than renting) lacks a shower. In Issue 4, she cleverly unscrews a pipe in the gap between walls to serve as a makeshift shower. As she perches between the walls, she imagines leaving town to find better living conditions. Still, there is a more innocent, isolated nature to Mel that makes it easier to sympathize with her than Faith.

Daydreams aside, Fray has no intention of moving: She sees Haddyn as being under her protection, as many superheroes feel about their stomping grounds. It’s partially because the city is home to her estranged sister, the cop Erin, and innocent paupers like the deformed 5-year-old Loo, who sees Melaka as a superhero even before she is officially anointed as the Slayer (Loo, in her broken future-English, calls Mel “the Slam”).

The world-building of “Fray” is delicious. As with “Firefly,” Whedon imagines language has gradually changed through the years, but where there’s a sense of evolution with “Firefly,” there’s a sense of devolution with “Fray” – although that could be because of what we’re privy to in these eight issues. “Grabbers” has replaced “thieves,” “lurks” has replaced “vampires,” and the syntax is more stunted.

Haddyn is reminiscent of the worst parts of Coruscant in “Star Wars” Legends. Up top are the civilized areas, which Erin and her police force mainly concern themselves with (and which we as readers rarely see). It’s department policy to not bother with the lurks, since they stay in the lower levels and prey on the downtrodden. As we see in the opening sequence of Issue 1, Melaka moves through the city by hopping between air cars and structures like Anakin Skywalker in “Attack of the Clones” and Ahsoka in “The Clone Wars.”

“Fray” is typical of post-apocalyptic fiction in that there is massive split between the haves and have-nots, the connected and the unconnected, but Whedon doesn’t tell us how this future came to be. Today, that’s not a problem; 21st century dystopian yarns don’t really have to tell the backstory, since we can read the news and imagine how “Fray’s” 23rd century grows out of our current times. But one line in Issue 3 (August 2001) strikes me as an intriguingly naïve pre-9/11 artifact. Erin and her partner have a wiretap on our titular thief, allowing them to track her. “This is inadmissible,” the partner notes. “No court’ll look at a subwave tap.”

The connection between the Buffy Summers saga and Fray’s saga reminds me of the Mirage “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” comics, where we got several glimpses of a horrific future (still within the Turtles’ lifespans). We were never given the connective material between the two time periods, although climate change was a theme the writers leaned toward.

There is still a storytelling gap between Buffy’s time and Fray’s time, and as with “TMNT’s” “present” and “future,” it may never be bridged (although the two Slayers have actually met, in a time-travel arc in Season 8). Even if it never is, that won’t diminish this miniseries. Common to Whedon’s elite works, the world-building is an important foundation, but still just a foundation. The biggest hooks are the personal journeys of Fray and the people around her. Despite all the comics Whedon has penned in the years since, “Fray” is still his masterpiece in this medium.

Click here for an index of all of John’s “Buffy” and “Angel” reviews.