In the third film where he handles directing duties along with writing the screenplay, David Mamet strips away all but the blackest of humor for one of his bleakest tales, “Homicide” (1991). I found this film admirable and engaging without actually ever liking it all that much. The main reason I couldn’t turn away was because I didn’t know where it was going.

With its title, I assumed it would be a cop-and-courts drama, but it has no courtroom component, and even though Joe Mantegna’s Bobby Gold is a homicide detective, it’s not quite a police procedural.

Double duty

While it’s not a typical procedural, “Homicide” is very much about the actual (rather than streamlined for entertainment) work this big-city detective does. It’s a rare screen story that shows a detective working two cases simultaneously, and this double duty is particularly irksome for Gold: He wants to focus on tracking down drug dealer Robert Randolph (Ving Rhames), but by being in the wrong place at the wrong time, he ends up assigned to the case of a Jewish grandmother who is gunned down while tending her convenience store.

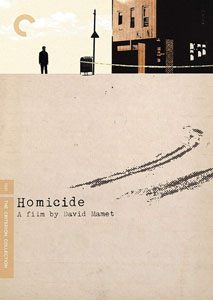

“Homicide” (1991)

Director: David Mamet

Writer: David Mamet

Stars: Joe Mantegna, William H. Macy, Vincent Guastaferro

Many Mamet films are not what they appear to be on the surface, leaving you with an impression of the people more so than the case or the con. But “Homicide” is the most extreme example, because it’s never about the details of either of these cases, but rather about how Gold feels about himself. As a Jewish person who endures racial slurs on the job yet knows little about his heritage, he feels like he doesn’t fit in anywhere.

Mamet, who is Jewish, illustrates this with details such as Gold’s partner Sully (William H. Macy) not understanding his interest in the murder of the Jewish woman, and also with a Jewish man’s exasperation that Gold can’t read Hebrew. It’s also interesting to note Bobby’s degree of hesitation before answering when someone asks if he is Jewish.

Mamet’s writing is naturalistic, with the cops talking over each other and exchanging vulgar insults at the precinct, but his direction feels stiff. It’s actually the same style he uses in “House of Games,” but the staginess fits better with that intensely plot-oriented picture. Mantegna’s performance is again understated, as with his turns as a con man in “House of Games” and a mobster in “Things Change.” Mantegna doesn’t give a big performance, but I sense his buried turmoil.

Inner and outer journeys

As we follow Bobby’s inner journey, which plays out through his outer decisions about which of the two cases to pursue (his boss’s orders be damned), “Homicide” meditates on the inevitability of the cycle of violence. Gold himself doesn’t think it can end, as he admits to Randolph’s mother that he, as a cop, is functionally a “garbage man.” The film’s thesis is clinched with the revelation of the shopkeeper’s killer, along with one other irony about a key piece of evidence, just before the end credits.

The final action sequence breaks free from the stiffness as Mamet gives us a harrowingly realistic death scene, a shootout that’s impressive considering it’s his first major action sequence, and a deliciously bleak showdown in an underground tunnel.

Cinematographer Roger Deakins nicely captures this setting, which would work great in a horror movie but also parallels the blackness of Bobby’s soul at this point. Indeed, the whole film captures Baltimore at its bleakest, making it a precursor to TV’s “Homicide: Life on the Street” and “The Wire,” both of which take place in Baltimore in addition to being shot there.

Strikingly, after the introduction of Bobby and his fellow cops, there isn’t a lot of humor in “Homicide,” even of the dark or ironic varieties. Mamet shows us Jewish culture and cop culture and a bit of black culture, and how violence is a perpetual cycle. By no means does he excuse law enforcement’s role, despite writing the laudatory law enforcement drama “The Untouchables” not long before this. There are no heroes in “Homicide,” but no pure villains, either.

Bobby Gold moves through a world where he doesn’t comfortably fit into any group, but the most uncomfortable realization for him and the viewer is that he wouldn’t want to fit into any of these groups anyway. “Homicide” is made with competence and conviction, but it’s depressing as hell, and a rare Mamet film with low rewatch appeal.