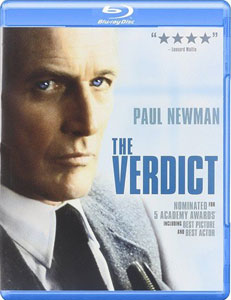

“The Verdict” (1982) is most known for the engrossing turn by Paul Newman as a down-and-out lawyer who gets obsessed with one case, but it’s also the pinnacle of the courtroom drama form under the eye of legendary director Sidney Lumet (“12 Angry Men”) and an early example of David Mamet’s chug-along writing.

While the film – rightly nominated for a Best Picture Oscar – is more than 2 hours long (a rare exception to Mamet’s 100-minute standard), it’s not boring for a second, and it’s worth that extra time as Lumet lets us soak up the details of Boston and the trappings of Frank Galvin’s dreary office and the grand courtroom.

A hardboiled lawyer

Working from a 1980 novel of the same name by Barry Reed, Mamet and Newman make Galvin into a hardboiled version of a lawyer. Although he is unquestionably in the suit-and-tie-wearing attorney role, a lot of his job involves pounding the pavement, like a noir detective. His assistant, Mickey (Jack Warden), also does this type of work.

“The Verdict” (1982)

Director: Sidney Lumet

Writers: Barry Reed, David Mamet, Jay Presson Allen

Stars: Paul Newman, Charlotte Rampling, Jack Warden

Additionally, Frank is an alcoholic who has only worked four cases in the past three years; he has resorted to giving his business card to widows at funerals of accident victims. As Frank gets obsessed with this case of medical malpractice against a powerful Boston religious hospital, he’s almost always at his office, with Mickey and Frank’s girlfriend Laura (Charlotte Rampling) also sleeping on the two couches.

Courtroom dramas have been a staple of movies and TV since the inception of those media, but “The Verdict” could work as a viewer’s introduction to the genre, or an exciting re-introduction. Lumet begins the third act with a wide-angle shot of the whole courtroom, 20 spectator rows deep.

Modern courtroom TV shows usually skip grand establishing shots, which is understandable since we’re in the same setting every week. But here, I sense the pressure and spotlight Galvin is under. Even when Lumet and cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak move closer to the action in the next shot, we still only see Galvin from behind the jury box. These choices communicate the scope of the trail – like a championship sporting event – and that doesn’t diminish until the verdict is read.

Accurate in its specifics

“The Verdict” feels accurate in both its medical and legal specifics, and I delight in the way Mamet’s screenplay brings quirky little details to the viewer. Desperate to track down a key witness, Frank and Mickey use the same alias on different phones, simultaneously, to try to acquire information. Insert shots (later a directorial staple of Mamet’s) convey loads of information.

For example, a shot of a plane ticket in Galvin’s pocket lets us know 1) that the woman he has tracked down has made the connection about who he is, and 2) that Galvin has purposely displayed the ticket so she knows, so he can cut the corner of introducing himself again. I also enjoyed less story-centric but still fascinating details, such Frank cracking an egg into his beer to get his day started – making him an alcoholic lawyer answer to Rocky Balboa.

Mamet and his collaborators use women in the hardboiled way where they aren’t fully formed characters like the men, yet the action pivots on them. Rampling’s Laura is a mystery woman who Galvin has seemingly courted, but perhaps she is actually pulling the strings. Maureen (Julie Bovasso) is the only nurse not testifying for the defense, but she refuses to talk to Frank’s team, too; what’s she hiding? And hard-to-find ex-nurse Kaitlin (Lindsay Crouse) might hold the final puzzle piece.

Not a pure mystery

“The Verdict” isn’t a pure mystery; we know generally what transpired to put the patient in a permanent coma, and we know Frank’s side is morally right and will win the case if he can complete the legal puzzle. For sure, there is some hand-wringing about the injustices of the justice system, but the film doesn’t stew in those moments; it instead shapes them into the most entertaining pieces of acting.

The verbal showdown between Frank and Judge Hoyle (Milo O’Shea) in the judge’s chambers is delicious. (Another nice detail: The judge is eating in almost every scene except when he’s in the courtroom. Other characters are often eating or drinking, too. I wonder if “Law & Order” was inspired by this.) Our peek into the smirky defense team’s strategizing is also informative: A lot of their efforts go into PR and perception, a contrast to Frank’s interest in facts, truth and justice.

“The Verdict” isn’t quite a down-the-middle, good-versus-evil film, though. The specifics of how Frank acquires certain pieces of information aren’t above board, and in the end, we can’t help but wonder if all the jurors make their decision based on the legal merits.

Ultimately, “The Verdict” is a celebration of a small slice of good that can give someone a pick-me-up in an unjust world. Like 2015 Best Picture “Spotlight,” which also exposes the shady doings of a revered Boston religious institution, “The Verdict” knows the path to achieve that slice of good is incredibly messy, and absurdly hard work.