Keith R.A. DeCandido, who wrote the solid “Serenity” novelization, checks into the Buffyverse with the series’ most heavily researched novel in terms of real-world details. It’s clear “Blackout” (August 2006) is close to the heart of the author. He lived in New York City as a kid in July 1977, the same time as the real-world 25-hour blackout and looting, and the time of the fictional showdown between Nikki Wood the Vampire Slayer and Spike.

The author gives us a good feel for how Nikki’s life, like that of many New Yorkers at this time, isn’t great, since there’s an economic downturn, police union squabbles, and the mayor’s controversial inmate work-release program – and it’s also miserably hot, a staple of many pivotal big-city superhero epics. But DiCandido’s memories of this time are nonetheless fond, and this is reflected in Nikki’s attitude. While Nikki doesn’t have everything, she has what she needs: a focus, and love, of the Slayer mission; her 4-year-old son, Robin; reliable Watcher Bernard Crowley; and several friends who work at the movie theater she lives above, some of whom babysit Robin.

Fans of the Netflix TV series “Luke Cage” (inspired by the comics that started in the 1970s) and the movie series “Shaft” (which gets a third-generation entry June 14) will also get a kick out of “Blackout.” Nikki’s ongoing battle against Harlem’s black-market kingpin Reet feels very much like how Luke Cage keeps criminals in check, without managing to eradicate them. Nikki is a local folk hero like Cage, with some Harlem residents knowing she’s the Slayer. DeCandido also throws in a note that Nikki once defeated a snake demon named Diamondback, clearly a reference to the human villain by that name in “Luke Cage.”

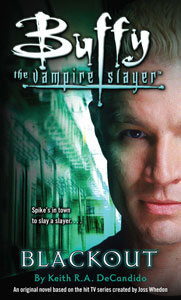

“Blackout” splits its perspective between Spike, who is on the cover, and Nikki, who should’ve shared cover billing. This is essentially a novel-length “Tale of the Slayer,” as Nikki is all about the mission, but she has a blast doing her job, fancying herself as a real-life Cleopatra Jones (from the Blaxploitation film series that’s contemporary with the heyday of “Shaft”). These elements continue from Nancy Holder’s “All About the Mission,” a 1973-set story from “Tales of the Slayer, Vol. 4.”

But in a continuity change that will be distracting if you’ve recently read the Holder story, DiCandido changes the point at which Nikki is called. In “All About the Mission,” she is already a Slayer under the charge of Watcher Crowley when she becomes pregnant with Robin. In “Blackout,” Crowley – assigned to Nikki because he’s already based in NYC — meets her soon after she is activated, when Robin is a newborn. While I admit that if Nikki is focused on the Slayer mission, she’d be less likely to be promiscuous and get pregnant, I’m not thrilled that DiCandido contradicts Holder’s story, especially since he could’ve incorporated it without sacrificing his own vision all that much.

Spike is in vintage form here, in town to catch a Ramones show at CBGB and to kill a Slayer. It’s always fun to see vampires who think they are the cock of the walk go up against this new blond British vampire in town, not knowing what they are in for; and it’s amusing when Spike muses about “grabbing a bite” or “enjoying a meal” and we know he’s referring to draining humans. As a bonus, the author also turns “Blackout” into a classic “Spike and Drusilla get back together after a spat” yarn, smoothly incorporating Dru into Nikki’s clash with Reet’s gang.

Although we know from “Fool for Love” (5.7) and “Lies My Parents Told Me” (7.17) that Spike will kill Nikki in their subway fight, that advance knowledge doesn’t diminish any of the tension. It feels “wrong” that Nikki should die, because she loves Slaying so much, and DiCandido even peppers in a resume (she has squared off with Darla and Dracula and averted several apocalypses) that puts Nikki on a level with Buffy’s exploits. But Nikki’s tale is ultimately a strong statement about the short lifespan of Slayers – even those who assume they are the exception – and the perspectives of Crowley and adult Robin give Nikki’s death the tragic gravitas it deserves.

The death scene also brings up a second notable continuity glitch – although this one isn’t as big as the overwriting of Holder’s story. In “Fool for Love,” Spike tells Buffy that Nikki had a death wish when fighting him, and this couldn’t be further from the truth in “Blackout” — either in the overall writing of Nikki, who has a zest for life, or in her fight with Spike. Diana G. Gallagher’s “Spark and Burn” fits with “Fool for Love,” in that Spike notes that he sees surrender in Nikki’s eyes before she dies.

DeCandido isn’t interested in that angle, instead writing that Nikki feels fear for the first time as Spike moves in for the kill. But that’s different from surrender, and indeed, she loses the fight because of bad luck (the train lurches as she goes for her stake), not because she gives up. To smooth out the continuity, the solution is that Spike sees something in Nikki’s eyes that he misinterprets. That’s a stretch, since Spike is a good judge of people, but it’s the best we can do. (On the other hand, Spike says he’ll say Nikki begged for her life when he retells this story, so he certainly has the capacity to lie, or to reimagine past events.)

Speaking as an amateur “Buffy” lore academic, I’m not thrilled that DiCandido chooses to overwrite Holder’s “All About the Mission” and Spike’s “death wish” assertion from “Fool for Love.” But I have to admit that as I was motoring through the 232 pages of “Blackout,” those points weren’t foremost in my mind. The details of Nikki’s life in 1977 Harlem drew me in to this story and gave me an appreciation for this little slice of history in the real world.

Click here for an index of all of John’s “Buffy” and “Angel” reviews.