Mere months after Batman got his first faithful big-screen treatment and ushered in a new era of dark and serious superhero films, “The Punisher” (1989) followed suit as arguably the most notable Marvel movie up to that point (even though it has since faded into more of a trivia answer than a movie people watch or discuss).

At first blush, it’s odd to bring Frank Castle to the big screen before Spider-Man or the X-Men or the Fantastic Four or the Avengers, but it makes sense in a way. The Punisher is a ready-made machine-gun-toting Eighties action hero. People already knew how to make this type of movie.

Punisher borrows from Rambo

“The Punisher,” directed by Mark Goldblatt and written by Boaz Yakin, is not hilariously bad; indeed, it is broadly competent. We get plenty of sequences of Frank (Dolph Lundgren) killing swaths of drug runners, sometimes in creative ways (his boots include retractable knives) and sometimes borrowing a page from Rambo and unleashing a hailstorm of lead.

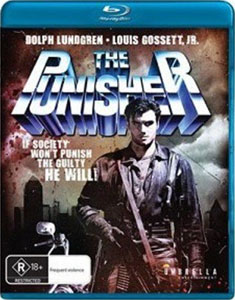

“The Punisher” (1989)

Director: Mark Goldblatt

Writer: Boaz Yakin

Stars: Dolph Lundgren, Louis Gossett Jr., Jeroen Krabbé

On their own, the fight scenes are effective in a gritty, DIY fashion, and some inch toward amusing, like when Frank mows down a roomful of martial arts warriors in an extreme version of Indiana Jones shooting the Cairo swordsman.

The problem with “The Punisher,” and the reason why it’s the weakest of the three “Punisher” films (all three pale in comparison to the Netflix series), is the characters. I want to be an apologist for Lundgren and claim there’s subtlety to this performance that most people overlook, but I couldn’t find it even when searching for it. Frank is numb and detached. Yakin gives him some good one-liners, but Lundgren can’t even deliver those with panache. Sometimes it’s hard to tell what he’s even saying, he’s so monotone and mumbly.

None of the traditional “Punisher” supporting cast is present. Some of the actors try to bring flair to their roles. The best, by default, is Louis Gossett Jr. as Jake, Frank’s former partner on the police force who very much disagrees with Frank’s extralegal approach of cutting a bloody swath through the city’s crime syndicates.

Yakuza leader Lady Tanaka (Kim Miyori) is the closest to a striking villain, especially when decked out in white face paint; she flat-out announces to local crime boss Franco (Jeroen Krabbe) that she’s taking over his operation. Barry Otto’s Shake, Frank’s street-level informant, is unusual in that he’s a once-proud thespian who speaks in rhymes, but this doesn’t quite make him interesting.

Not much at stake

There are surprisingly little personal stakes in the 1989 movie considering that Frank notoriously takes everything personally. As always, Frank’s wife and kids (two young daughters in this telling – for some reason the number and genders of his kids isn’t consistent across the four screen versions) are killed by bad guys. Frank kills the perpetrator, Dino Moretti (Bryan Marshall), in the opening sequence. Frank’s involvement in the clash of the two mobs comes about because innocent kids have been kidnapped as part of it.

But the theme of Frank secretly being and old softie who will do anything for kids, seeing them as surrogates for his own, doesn’t come through. This is partly because Frank kills one – a mute white teen girl (Zoska Aleece) who was adopted and trained by the Yakuza in martial arts – as part of his mission, and then tells the even younger Tommy Franco (Brian Rooney) that he’ll be waiting for him if he grows up to be as evil as his dad.

Any sense of Frank as an ironic father figure is blunted, to say the least. The filmmakers especially had something out-of-the-box interesting with the white girl raised to be a Yakuza assassin, but they apparently didn’t realize it.

The biggest flaw with “The Punisher,” though, is the Punisher himself. With his hair dyed black, Lundgren looks and acts the part, but in a lifeless manner. The film doesn’t try for the depth we’d later see in the Netflix version, but you’d think it could at least lean the other way and be over-the-top fun like a “Rambo” sequel; instead, Frank’s demeanor and the movie’s overall tone are oddly restrained.

Even in his closing voiceover, meant to give some perspective on his grim lifestyle of living in the sewers (yep, there was a sewer-dwelling superhero a year before “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles”) and killing baddies, Frank sounds so bored that I didn’t even register what he was saying. It’s probably some down-the-middle cliché … which I suppose is an appropriate way to conclude this movie.