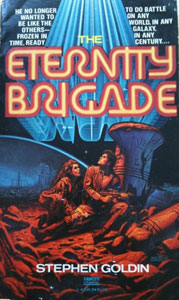

Inspired by Joe Haldeman’s “The Forever War” (1974) but not copying it, Stephen Goldin delivers a lesser-known but still great treatise on the dangerous intersection of the military, technology and the sanctity of individual freedom in “The Eternity Brigade” (1980 first edition, 2010 revised edition). Although Goldin often has his heroes state the story’s themes in their dialog rather than letting things play more subtly, his imagination clicks on all cylinders as he brings us into a world where soldiers can be resurrected from every battlefield death.

An odd definition of freedom

Goldin’s point-of-view hero is Hawker, who chooses the military life because he is scared of civilian life and finds an odd “freedom” in his choices being made for him. His friends are Green, a Jewish man from a puritan upbringing, and Symington, a big guy who likes to party.

Belilo, a woman who has sex for the fun of it (a common old-school sci-fi novel staple), and a few other friends pop into Hawker’s life as well. Even though “The Eternity Brigade” covers the grimmest of subjects, the steady presence of Hawker’s friends often makes it an incongruously happy read.

“The Eternity Brigade” (1980)

Author: Stephen Goldin

Genre: Science fiction

Setting: Near future, various planets

Another reason we don’t dwell too much on the negative side of constant resurrection (or “dubbing,” as it’s called here) until later in the narrative is that the science is so fascinating. Goldin first explores cryogenic freezing, then moves his way up to the regeneration of molecules. We’ve seen these concepts in many sci-fi movies – cryogenics in “Alien” and molecular regeneration in “Star Trek,” for example – but seeing them through the eyes of Hawker shows the human toll.

At first, there seemingly isn’t any cost; indeed, Hawker and his friends marvel at how easy it is. And an unwritten protocol develops to handle the wiggy aspect of regeneration: If a soldier dies on a previous mission (and therefore does not remember it, since the military therefore reverts back to the last-saved version of the person), his fellow soldiers don’t talk to him about that mission.

In fact, to avoid accidentally saying the wrong thing, they stop talking about the past. And since the future is more unpredictable than ever, given the potentially long time lags between dubbings, they don’t talk about the future either. While it has been stated in some philosophical thought that it’s important to focus on the present, a life that’s only about the present moment arguably lacks wider meaning, and “The Eternity Brigade” illustrates this. (Sorry, Qui-Gon Jinn.)

The psychological cost

I like how the cost is psychological and only gradually realized by Hawker. Goldin gives us some harrowing war anecdotes – including enemies amusing themselves by forcing male prisoners to rape female prisoners in an Antarctic war – yet the ultimate horror and the point of the novel is that Hawker keeps living. But he’s not really living, he’s existing. He’s not a robot, but he might as well be.

“The Eternity Brigade” is a 271-page war novel, but it’s not about one war, it’s about many wars over the course of centuries, starting with present day. (Originally, the present day was 1980, but Goldin updated the book in 2010, adding terms such as iPod. Since most SF fans don’t have trouble adjusting to books written in the past, I’m not sure this was necessarily. And it arguably creates a flaw since the emphasis on one soldier’s black skin is retained, an odd element for a modern novel.)

Even in specific battles, tactics, location and even the identity of the enemy are rarely discussed in detail. This isn’t a flaw, but rather one of Goldin’s points, and it reaches darkly comedic heights with the revelation of who Hawker faces off with in a final battle on some random planet.

Even through the narrow lens of the battles that Hawker and friends are dubbed for and thrown into, Goldin shows imaginative extrapolations about the course of humanity. Memorably, some beings in the far future are part of the human lineage but they’ve changed so much that they look like another species. Language also changes (instant knowledge uploads help the soldiers adjust), as do the moral values of the spinoff races.

Although Goldin sometimes states his themes bluntly, I do find it fascinating that Hawker reflects on how life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness have all been bastardized. I don’t think “The Eternity Brigade” is a strictly anti-technology novel, but Goldin shows concern about what governments and militaries could do with amazing tech – to the point where death is not merely the last escape for a soldier, it’s an ephemeral and desperately desired one.