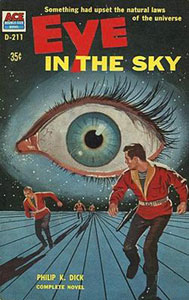

“Eye in the Sky” (1957) is one of Philip K. Dick’s most influential novels – or at least prophetic of what future authors would explore – as he delves into subjective realities. Also explored in his short story “The World She Wanted” (1953), “subjective reality” is the idea that everyone’s perception of the world comes from inside themselves rather than outside.

Influential theme

Michael Crichton delivers his entry in this subgenre with “Sphere” (also made into a movie), where people’s fears become reality thanks to an alien object. The “Buffy” episode “Superstar” shows a world as magically manipulated by Jonathan. The best episode of “Kolchak: The Night Stalker,” “The Spanish Moss Murders,” is about a creature manifested by a person’s dreams.

PKD didn’t invent subjective realities. “Forbidden Planet,” which features a manifested monster, came out a year before “Eye in the Sky,” and that movie is drawn from Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.” But PKD’s novel is a richer exploration of the theme.

“Eye in the Sky” (1957)

Author: Philip K. Dick

Genre: Science fiction

Setting: Undated, Belmont Bevatron

The group of eight people who fall through the beams of the exploding Bevatron (an atom smasher of sorts) spend time in the minds of the four most eccentric people of the group. In actuality, they are still on the floor of the Bevatron chamber, unconscious, so “Eye in the Sky” isn’t about a bleeding of realities but rather the idea that everyone sees the world differently and distinctly. In that way, PKD touches on mental illness and suggests it’s more common than generally assumed.

The first and best of the four alternate realities – as experienced by the reader via protagonist Hamilton, a scientist — is that of the God-fearing Arthur Silvester. The rules of his universe come from (loosely speaking) the Bible, so if you want something you pray for it. It’s humorous how society is still structured the same: For example, Hamilton has a job with a salary, but the way he gets the salary is to pray for it. During the prayer, he is to inform God of the position he holds at the company, and then he’ll receive the commensurate salary.

Multiverse of the mind

This segment, which gives the book its title since Arthur imagines God as a giant Eye looking down on us, could be read as a parody of religion. Or it could be PKD’s extrapolation from organized religion’s power in 1957 to a society where the collective consciousness of prayer becomes robust enough that prayers are answered in regular, predictable and recordable fashion.

The reality of Mrs. Pritchet, who is annoyed by most everyday facets of life, is funny but overlong. She keeps wishing things – from female sex organs to semi trucks — out of existence until there’s nothing left. Next up is Miss Reiss’ reality, which is like something Stephen King would later write: Hamilton’s house comes alive, a manifestation of Reiss’ paranoia about other people.

With the last alternate reality, PKD critiques America’s Red Scare period in a chaotic fight between capitalists and Communists in the streets of a Bay Area suburb.

When everyone wakes up in their hospital beds in the real world, PKD shows that objective reality isn’t all that much more nonsensical than the minds of paranoiacs. Hamilton’s wife, Marsha, is accused of showing Communist leanings by one of the executives at Hamilton’s company, which makes weapons for Uncle Sam.

McFeyffe is actually the Communist, as Hamilton had learned while in the man’s subjective reality, and he’s turning suspicion to Marsha as part of his complex “ends justify the means” scheme. Hamilton tells his boss that it’s a shame the methods and logic of the spy/security state don’t extend to those in power, such as McFeyffe. It’s a nice illustration of a core problem of both police states and Communist states – that a certain class is exempt from being spied on or from being as equal as everyone else.

Cult of the individual

Reflecting an idea also explored in “The Chromium Fence” (1955), PKD shows sympathy for people (including himself, no doubt) who don’t belong to either of the two mainstream belief systems. In the short story, it’s Purist versus Naturalist, with the non-binary option being to let people decide for themselves. In “Eye in the Sky,” it’s Communist versus capitalist, with the non-binary option being individualist.

To the secret Communist McFeyffe, Marsha is worse than his clear enemy, capitalists, as he explains to Hamilton in chapter 16. It’s interesting that McFeyffe categorizes Marsha into a “cult” (aka group) of individualists, a way to define her through his own lens, which villainizes individual thought:

“They don’t belong to any group. They fool around with everything. People like her – they’re more a menace to Party discipline than any other bunch. The cult of individualism. The idealist with his own law, his own ethics. Refusing to accept authority. It undermines society. It topples the whole structure.”

PKD perhaps accidentally includes some insight into how he sees marital relationships in via Hamilton’s treatment of his wife. Hamilton openly flirts with a bar regular, Silky, even with his wife present. The love triangle is both archaic — PKD plays this as something Marsha should adjust to, more so than bad behavior by Hamilton – and progressive, in that the author is presaging the free love era.

Hamilton’s notions of how a husband should behave will meet criticism from many modern readers, but then again, the mystery of “Eye in the Sky” could only be navigated by a scientist who is not bound by conventions.