Setting aside the fact that time travel is by its very nature crazy, “Dr. Futurity” (1960, expanding from the 1954 short story “Time Pawn”) is a pretty straightforward novel by Philip K. Dick standards. It would be mind-blowing for a reader experiencing their first time-travel story, but it’s par for the course for modern readers well-versed in “The Terminator,” “Back to the Future” and “Avengers: Endgame.”

Timeless possibilities

PKD appreciates the possibilities of time travel. Inadvertent time-traveler Jim Parsons (no, not that one), a doctor in 2012 San Francisco who gets time-dredged to 2405, soon finds himself thinking in terms of time as an always accessible game board – in other words, he can’t escape his enemies by traveling to a different point in time. On one journey back to the 16th century, Parsons notes that there are five time ships scattered amid a scene where multiple parties are trying to alter history.

That’s an amusing image for sure, but “Dr. Futurity” still lacks that next level of Dickian absurdity; unlike most of his books, this one could’ve been written by any competent SF author of his era. Another thing that makes it somewhat un-Dickian is that he explores different possible cultures rather than focusing on the oddities of the 1950s California culture around him and extrapolating that into the future, thus satirizing it.

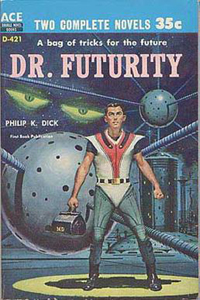

“Dr. Futurity” (1960)

Author: Philip K. Dick

Genre: Science fiction

Setting: Future 2012, San Francisco; 2405

The story’s structure is somewhat like H.G. Wells’ “The Time Machine” (1895) in that Parsons travels to the future and sees a different culture. But Wells is using the Eloi and Morlocks to comment on his own time; that’s what PKD would usually do, but not here. (Both novels do feature the protagonist traveling to the end of Earth’s time. Both are melancholy experiences, but in different ways.)

In 2405 – which must be among the most far-future dates in a PKD story – Parsons discovers that the practice of healing is outlawed. It’s like one of those “Star Trek” episodes where Kirk and company teach an alien culture where it has gone wrong (forgetting about the Prime Directive as always). The 2405 culture values a relentlessly stable population number as a bulwark against overpopulation and resource shortages.

Different values

It’s not clear if PKD himself believes these are valid fears or if he believes populations can adjust with the fluctuations in numbers. But certainly he – and we, the reader – take the side of Parsons, who is arrested for healing a woman who would’ve otherwise died from her injuries in a political skirmish. In a haunting twist, the woman kills herself when she realizes to her horror she has been saved – something that goes against this society’s deeply held beliefs.

Then Parsons ends up with a cult hidden in the outskirts of San Francisco – one that believes in the old-fashioned ideas from Parsons’ own time, including natural childbirth, but also the older notion of racial purity.

PKD puts himself in the tricky position of having this cult – closely descended from Iroquois Indians, we’re told – be racial purists but also the good guys of “Dr. Futurity.” For the book’s climactic final act, the author focuses on the time-travel machinations in which Stenog (from the mainstream 2405 society) and Corith (from the Indian cult) repeatedly battle in 1579 in order to establish their point of view’s dominance throughout history. Or something like that.

I like the idea of using Drake’s (no, not that one) landing at New Albion, north of the Bay Area, as a pivot point. Even though this is fairly straightforward reading, some things don’t make sense upon reflection. The Indians have done enough time traveling to know that time functions like a river: It finds its natural course again. So a time traveler creates a ripple in a river, not a new branch. If that’s the case, all the time travel in “Dr. Futurity” is futile.

Furthermore, by focusing on time travel, PKD excuses himself from touchier — yet perhaps interesting — subjects. If the Indians are racially pure, then the matriarch, Nixina, must’ve traveled forward via the time machine. But that’s not explained.

Race and racism

The group’s deliberate system of inbreeding is similar to what must’ve happened in the wake of the Adam-and-Eve story, and PKD doesn’t exactly sympathize with this approach (Parsons is shocked), yet it’s not a major issue, either. Loris, the granddaughter of Nixina and now group’s younger female leader, eventually just admits inbreeding is a bad idea for the long term.

In addition to being about race, “Dr. Futurity” also tiptoes into racism. Parsons is white and therefore a freakish outsider to the mixed-race San Francisco residents of the future; this is of course a blunt flipping of the script from PKD’s time of legal and societal segregation along black-white lines in the USA.

The author is somewhat smitten with Native Americans, or at least Parsons is smitten with Loris and her “superb breasts.” (He also admires the look of the mixed-race people, mulling the notion that mixing races is a path that leads to a superior brand of human being.)

On the other hand, when weighing the options of being stuck with an Indian tribe or with Europeans in the past, Parsons immediately prefers the latter option – and he suspects the 2405 Native Americans would too.

I like “Dr. Futurity” more than some other early novels like “Vulcan’s Hammer” and “The Cosmic Puppets.” PKD is more engaged and focused here, and Parsons – by being a doctor rather than a bureaucrat or a random selfish dude – is a more likable (if not exactly dynamic) protagonist. The novel doesn’t reach its full potential with the themes that are set to the side, but it is a brisk page-turner, especially if you dig time travel and its associated theories.