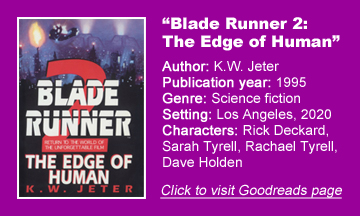

Back when a “Blade Runner” movie sequel seemed unlikely, Bantam (the publisher of “Star Wars” spinoff fiction at the time) and author K.W. Jeter delivered three follow-up novels from 1995-2000. The first, “Blade Runner 2: The Edge of Human” (1995), returns us to the world of the film nine months later, and the author paints a picture with words as beautifully as Syd Mead and his team created the movie’s dystopian Los Angeles.

Poetic hardboiled writing

As Deckard is recruited by Sarah Tyrell, the niece of the late Eldon and heir to the corporation, to find one last escaped replicant in August 2020, Jeter delivers poetic hardboiled writing. It’s objectively overwritten, but it doesn’t matter because Jeter writes so well, and about the subjects we’ve come here for – namely the difference between humans and replicants, which is increasingly hard to decipher.

Before “Blade Runner 2049” (2017) settled the question, it was a popular pastime among fans to ask whether Deckard himself is a replicant. Jeter taps into that along with the relative humanness (in both literal and spiritual senses) of everyone else. Holden – blown away by Kowalski at the opening of the film – is back on his feet, but with an artificial heart-and-lung setup.

Sarah is the human templant (the real person the replicant is designed from) for Rachael, and older-looking bounty hunter Roy Batty is the templant for his replicant version from the movie.

With “The Edge of Human,” the “Blade Runner” saga joins the “Terminator” spinoff materials in imagining that artificial humans are modeled after specific people. And – because it’s basic good business to run an assembly line rather than doing custom jobs — there are several of each model, as we learn in a harrowing “Westworld”-like scene of a train car full of naked replicants being hauled out of town to their destruction.

“Templant” feels like a Philip K. Dick word, but it’s Jeter’s, although the author does use “ersatz” and “simulacra” once each. Jeter doesn’t remotely try to mimic PKD’s writing style – which is the right choice, as this is a direct “Blade Runner” sequel, and the movie likewise has a tone distinct from PKD despite drawing from the plot and themes of “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”

Peppering in some PKD

The “about the author” segment claims that “Edge of Human” “resolves many of the discrepancies” between “Blade Runner” and “DADOES.” That sounds confusing, but thankfully that’s not really what this is. The narrative is a straight sequel to the movie, but it includes elements of Dick’s book as new characters and plot points for this world.

The stuttering Isidore is a pet salesman in “The Edge of Human.” Sebastian, the film character based on Dick’s Isidore, who worked for Tyrell designing Nexus-6 replicants, is also on hand.

Jeter also brings the Salander 3 mission into the fold. Sarah, not Rachael (as suggested in “DADOES” in the scene where Deckard runs the Voigt-Kampff test on Rachael), really did travel beyond the solar system with her parents. They came back to Earth dead, and she was an emotionally scarred child – who would become further scarred under the “care” of her uncle Eldon.

Readers of the “Star Wars” “Bounty Hunter Wars” trilogy will be familiar with Jeter’s tactic of his characters analyzing moments from the films and spinning off deeper intrigue from there. It’s a contrivance, but I like it, and he does the same thing with “Blade Runner.” It fits better here, because it makes sense that an oppressive government and powerful corporations would have spy bugs everywhere.

Through this device, Jeter takes “Blade Runner’s” plot holes (brought about by different screenplays being melded together during the famously rough making of the movie) and turns them into intrigue – notably Bryant’s inconsistency about how many escaped replicants are loose in L.A. He also gives a reason for how the heck Kowalski smuggled a gun into his interview with Holden.

Sour Deckard

The author nails the sour character of Deckard, who goes through the blade-running motions but is only thinking about Rachael – who he has left in stasis up at his Oregon hideout. (The stasis “coffin” is reminiscent of Dick’s half-life cold-pacs, most famously used in “Ubik,” wherein a dead person has a little bit of life left that can be used for conversing with loved ones in short bursts.)

It’s similar to “DADOES’ ” sheep-obsessed Deckard, but also works for Harrison Ford’s take on the character. He doesn’t talk or even brood much about the human-replicant borderline or what his job has done to him, yet he represents the saga’s themes better than anyone.

The relationship between Sarah and Deckard is not a traditional love story, but it fills the hole where a love story would normally go. Jeter can spend pages digging into what it means to be human (especially in the Holden-Batty debate), but on the other hand he never overtly states what Sarah’s goal is, and yet I picked it up: She wants Deckard to love her the way he loves Rachael.

Considering how shallow – if highly romanticized through filmmaking style – the Deckard-Rachael relationship is, the sequel’s ersatz romance is a natural fit for the saga.

“The Edge of Human” is an expertly crafted piece of dystopian hardboiled fiction. We soak up the imagery of rundown L.A., the intrigue of an internal police conspiracy against blade runners, and action where people get blown away by huge guns pulled from trench coats.

Yet we are left with the beautifully pathetic nature of Deckard’s and Sarah’s search for something more. I expect Ridley Scott, PKD if he were still alive, and fans of both of their work would approve.