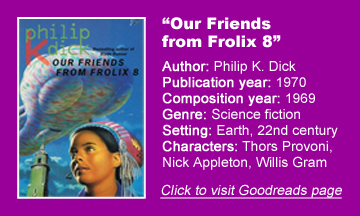

“Our Friends from Frolix 8” (written in 1969, published in 1970) kicks off Philip K. Dick’s thematic police state/drug war trilogy, and although “Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said” and “A Scanner Darkly” won more awards, this one is nearly as great.

PKD satirizes and/or paints the likely progression of an all-seeing state, but for the first time the author finds an answer to why the masses don’t openly rebel.

A beaten-down protagonist

In most of Dick’s works, the protagonist – even if desiring a better world – is beaten down and accepting of his lot in life. Nick Appleton is no different, but “Frolix” also spends a lot of time showing the POV of Gram, the ruler of the Earth government in the 22nd century.

Gram and his officials use Nick as a randomly selected sample man from which to learn about the thought processes of “Old Men” (people who don’t have the advanced brains of “New Men” or the telepathic powers of “Unusuals”). The government monitors and/or arrests “Old Men” who join the “Under Men,” people who actively consume literature and advocate for rebellion.

They learn that most Old Men don’t join the rebellion not because they don’t believe in its cause, but rather because they are more concerned about their personal lives – for example, their next paycheck.

Nick’s specific case is a variation of PKD’s usual married-man arc wherein he leaves his wife (named Kleo, not coincidentally the name PKD’s wife from the previous decade) for a younger woman, in this case teenager Charley.

In Nick’s eyes, Charley is alternately an utterly fascinating and lively young woman or a “gutter rat.” Regardless, she’s all he thinks about. Nick may be a slave to lustful feelings, but Dick’s writing on this matter rings true.

Dark reality, dark humor

Taking the dark humor further, Gram – whose office doubles as his bedroom, like he’s a human Jabba the Hutt — desires to use his power to make Charley one of his concubines. Just as Nick is distracted from rebellion by a cute girl, Gram is distracted from ruling over the human race.

Nick feels this way despite the fact that he lives in one of the most brutal police states in any PKD book; people always adjust to their surroundings, after all. They know to be careful about possessing revolutionary co-leader Cordon’s “tracts” (writings), because the government has records on everyone.

Mass data collection is old hat to readers in 2020, but even some “Frolix” Cordonites are surprised by how deeply the state can see into their lives, so PKD’s 22nd century date for this novel is arguably a vast underestimation. (Of course, one could argue that state power ebbed and flowed in the intervening years.)

Additionally, the government is developing a “Big Ear” and it already possesses “peep-peep screens.” PKD gives us some insight into how spying became legalized via a fiscal-responsibility justification on page 102, when an official tells Nick the original reasoning was efficiency. But now 1 million employees man the screens; government tends to grow, not to contract.

We already see signs in the real world of public-sector jobs holding more appeal than private-sector jobs because those positions can be maintained beyond the point of their usefulness and they are more resistant to layoffs. For example, during the mandated shutdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic, you hear far less about government cutbacks than about free-market belt-tightening. ‘

The fight for government jobs

And in “Frolix’s” 22nd century, state jobs are clearly more desired. Old Men take tests to try to get one of these jobs, not knowing the game is rigged – something Nick finds out when his son Bobby’s test includes questions that can only be answered by big-brained New Men.

Most citizens do nothing more than quietly rebel through language. PSS police officers have become “pissers.” “Officer,” in fact, has become “occifer” – although here PKD might be playing with random language evolution; he also makes “phone” into “fone.”

Some of this world is perfectly normal to those living in it, but humorous to readers. PKD makes fun of the arbitrariness of the War on Drugs by showing that drugbars are legal but alcohol is illegal in the “Frolix” reality. Apparently the lobbying groups’ relative power flip-flopped in the intervening century.

The author later tiptoes into the themes of “A Scanner Darkly” when the New Men’s brains get destroyed on a mass level and they revert to “kiddies”; I wouldn’t be surprised if he was thinking in terms of recreational drug side effects.

Perhaps the clearest way Dick illustrates the entrenched nature of the police state is the casualness of Gram’s decisions. He orders Cordon to be murdered via a written order to a state hitman. Although the state-influenced media gives a false account that Cordon died of a health ailment, Gram isn’t all that concerned about having a tight cover-up.

A fickle leader

At various points, Gram orders the killings of Nick and Charley and then changes his mind. And the notion of releasing Under Men from concentration camps is entirely seen as a political maneuver by Gram, who never sees anything in moral terms.

All of this is not to say that people who want a better world but take no overt action are useless to revolutionary groups. “Frolix” argues that if there’s a tipping point, all of those dormant revolutionaries will join the cause.

In this case, the tipping point is the arrival of a giant multi-ton Frolixan named Morgo, who has been retrieved by space adventurer Provoni, Cordon’s Under Man co-leader.

(Morgo is the spaceship in the Voyager cover art above. I have no idea who the woman is supposed to be – maybe a generic New Man government worker, with her head wrappings covering her large brain.)

So as grim as “Frolix” is in portraying an oppressive state, it’s equally hopeful in dreaming up an alien as a helper rather than a malevolent being – a contrast to, for example, “The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch.”

Nation-building alien

Morgo, who is unable to lie and is so powerful that he can stop wars with his mere threats of retaliation, promises to help install a new government that will be based on elections rather than appointments. As we know today, that makes little difference, but Dick’s point is taken.

Ironically, Morgo’s nation-building parallels the USA’s similar policy, which has led to debacles such as Vietnam in the 1960s and the Middle East in the early 21st century.

Since Dick was no fan of the Vietnam War, this is an odd choice at first glance. But I suppose this is why he takes pains to illustrate that Morgo has earned his superior moral and power position through demonstrably peaceful and self-defensive actions.

In terms of writing quality and world building, “Our Friends from Frolix 8” is a smooth, polished novel. It thoroughly explores its ideas rather than throwing them at the wall and moving on to the next one.

While we can find these same themes in other PKD books, this one puts them together differently and gives us a rare upbeat ending. Underrated in terms of awards and accolades, it deserves consideration as one of Dick’s best books.