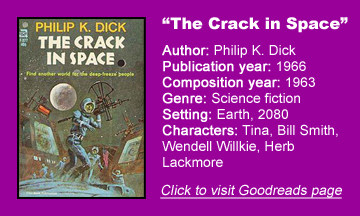

“The Crack in Space” (written in 1963, published in 1966) is an unusually earnest novel from Philip K. Dick, who tackles American race relations through one direct thread and one metaphorical thread, and who even includes an epilogue outlining his points. It’s both dated and timely, stuck in both the 1960s and in a pulpy SF journey that takes us from the dawn of man to 2080.

The first black president … in 2080

It’s dated in that PKD tells the “futuristic” story of the first black president, and we’ve now had that experience in America. PKD imagines the first black (“Negro” in his terminology) president will take office in 2080. In reality, Barack Obama took office 72 years before the author’s prediction of Jim Briskin’s presidency.

Although he is half-black, half-white – which is actually a great symbol of unity – and although he is culturally and politically white in many ways, the popular perception of Obama is that he is “the first black president.” It’s highly unlikely that the first 100 percent black president will usurp that title in popular nomenclature.

PKD also imagines the lead-up to Briskin’s election will be heavy on racism, including a protest group whose views mirror 1960s segregationists. A reader can presume that PKD’s guess of 2080 is so far off because he didn’t foresee a gradual softening in the harshness of race relations from the perspective of the civil rights era.

That said, “The Crack in Space” is timely because there still is plenty of racism today. Hot-button issues during the era of our first black president and beyond have included relations between the police and black citizens, fear of Muslims in the wake of 9/11, and dislike of Hispanics on immigration grounds.

Fear of youths, immigrants

Adding to the modern relevance, there’s a decided young-versus-old conflict in the book in regards to job availability. People are living longer – as much as 200 years – and many young adults who would ordinarily enter the job market instead choose to be cryo-frozen by the government with the promise of being unfrozen when jobs are available.

“The Crack in Space’s” immigration fears are based on both the theory of “overpopulation” (which would coincide with limited resources) and bigotry. With attempted terraforming of Mars and Ganymede a bust, our protagonists – most of whom are in political or corporate spheres – jump at the idea of human emigration to a parallel Earth (think “Sliders”) that has been discovered in a defective Jiffy-scuttler (think the transporter room from “Star Trek”).

Readers of the short story “Prominent Author” (1954) – which is referenced as backstory here – will be familiar with a time-space rip in a ’scuttler. In that case, a man visits ancient people through the rent in time and accidentally writes the Bible.

Here, it’s a dimensional rent, and on the alter-Earth are dawn men, specifically the type known as Peking Man. When he wasn’t researching Nazis, PKD obviously dipped into early humans, as his fascination with the subject also pops up in “The Man Whose Teeth Were All Exactly Alike” and “The Simulacra.”

Since the dimensional gate goes both ways, the humans are mildly concerned about the Pekes coming to an already “overpopulated” Earth. But they are much more concerned about interbreeding – which could mean the end of Homo sapiens as we know it.

War is assumed

And the biggest fear of all is war. Briskin and the other main characters take it as a given that humans and Pekes will be at war if they share the alter-Earth, a straight repeat of European colonization of America on our own Earth.

Scholars and communications experts on the initial excursions to the alter-Earth establish relations with the Pekes, but they are in the background. The main characters brace for inevitable war, not even entertaining the idea that Jeffersonian friendships between nations could be established.

The chapters wherein humans go to the alter-Earth and explore it make for good reading, but PKD doesn’t quite sell the notion that the Pekes are threatening. (Eventually, we learn that they are. But that’s only because someone from our world secretly manipulates them.)

“The Crack in Space” is a particularly political book, even by the standards of an author whose protagonists are often bureaucrats. The 2080 election is of course on the mind of Briskin, as well as several people in his sphere.

The dimensional rift’s possibilities for emigration and the fates of the cryo-frozen young people are totally viewed through political lenses. It all rings true; this is not PKD’s usual satire of politics, but rather a straightforward portrayal of the fact that governmental decisions that affect the masses are always political rather than practical or logical.

PKD’s abortion obsession

The book specifically tackles abortion, something that wrenches a reader from 2080 back to 1966. Abortions are not called for too often in this society because men work out their sexual urges at a satellite space station pleasure palace. PKD briefly mentions contraception, but suggests that it’s unreliable at this time. (By the same token, we have to assume the satellite sex workers are sterile or have excellent contraceptives.)

When a woman does get pregnant, she can safely get an abortion. However, this isn’t exactly a pro-choice novel.

We know from the infamous “The Pre-persons” (1974) that PKD was stridently pro-life. “The Crack in Space” isn’t nearly so snarky and aggressive as that short story about 12-year-olds being aborted, but PKD’s viewpoint comes through via abortion doctor Myra Sands.

When the alter-Earth opens up the promise of new settlements and natural resources, Sands knows the demand for abortions will drop and she’ll be out of a job. But she’s glad for it, because deep down she always thought what she was doing was wrong. To close chapter seven, PKD writes:

At least she could go to bed tonight with a clear conscience. For perhaps the first time in years.

While “The Crack in Space” is another one of those PKD books that blends too many ideas – indeed, a tabloid-headline-grabbing divorce between Mr. and Mrs. Sands has nothing to do with the main thrust and is mostly forgotten – it is more thematically focused than most of his “hodgepodge” books. I said the same thing about “The Simulacra,” but that book is purposefully weird. This is another wild ride, but it’s accidental this time.

“The Crack in Space” has its bizarre moments, but PKD doesn’t try to be funny or satirical here; he’s soberly (by his standards) exploring bigotry, overpopulation and immigration through a political lens. Not everything lands, and not everything has aged well as a reader is bounced between prehistory, 1966, our present day, and 2080. If you hold on tight, though, a lot of this novel remains timely.