It’s tempting to think of the last four books Philip K. Dick book wrote – all after his 1974 beam-of-pink-light experience – as his crazy religious books, but that’s not entirely accurate. “VALIS” is a little out there, sure, with both Phil and Horselover Fat participating in diner chats even though they are the same person.

But “The Divine Invasion” is a creative reworking of the Bible myth, and “Radio Free Albemuth” is a low-key good-versus-evil battle where Dick returns to the blue-collar West Coast workplaces of his 1950s realist novels.

A sane person versed in craziness

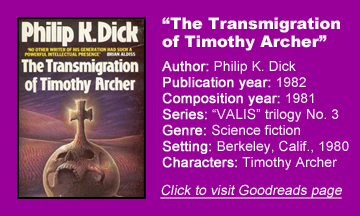

And with “The Transmigration of Timothy Archer” (written in 1981, published in 1982), PKD goes out on top with yet another professionally crafted, never-silly novel. Although he couldn’t have known this would be the last novel before his untimely death at age 53, it’s remarkable how crisply this is written as it puts a bow on the spiritual concepts important to the author at this time.

This is a novel by a sane person well versed in craziness. Dick got his quest-for-God obsession out of his system with “Invasion,” and now he pens a deliciously accessible religious mystery.

The titular Bay Area-based bishop has learned of Zadokite Documents in the Dead Sea Desert that spell out the teachings of Jesus Christ a century before Jesus’ time.

Even for an atheist reader, this is juicy stuff; Timothy knows that if the documents are genuine, that means Jesus was a disciple of the actual Christ figure, and also that some things taken as metaphorical (such as the Eucharist) have literal precedents. This would be world-shaking, whether you’re a Christian or not.

What’s great about Archer as a character – since this is a talky novel – is that he doesn’t merely spout doctrine. He’s well-read in a variety of texts, and he lets evidence rather than faith lead him to conclusions – so much so that he decides to leave the church because he doubts the accuracy of what he’s teaching to his congregation.

The stakes of obsession

As good as the mystery is, “Transmigration’s” biggest strength is how it leaves us pondering the psychological stakes of obsession on Timothy and his loved ones.

The book is about the acquisition of information and the quest for knowledge, and we see how even the open-minded bishop is influenced when he wants to be led in a certain direction – namely when he latches on to the idea that his son, Jeff, has returned as a spirit.

The book is told entirely from the first-person point of view of Jeff’s widow, Angel. She narrates from Dec. 8, 1980 (the day John Lennon died), reflecting on the deaths in recent years of her husband; Tim’s lover Kirsten; and Tim himself. She sees the flaws of Tim’s path from an outside perspective that’s essential to the reader – even though she reveres the bishop’s knowledge and is internally hard on herself.

As it turns out, she is by far the most grounded, selfless and moral of the bunch, and the only one making an honest living (as a record store manager, which is a solid job in 1980).

Jeff is a career student at Berkeley, with Angel supporting him; the bishop uses his discretionary funds to pay for his secret lover’s apartment; and Kirsten is happy to take that free money. Angel is also the only one who recognizes the wrongness of Kirsten’s son Bill being in and out of the psych ward.

Harking back to the Fifties

To honor Lennon, radio stations play Beatles tunes on heavy rotation, as if it’s the Sixties again. As Angel looks back on the loss of three loved ones and the regrets in her own life, there’s a low-key sad nostalgia to “Transmigration.”

We’re lulled by Angel’s life experience, so Tim’s titular “transmigration” into his lover’s son Bill plays as a nice surprise. In a way, we should see it coming: It puts the book in the religious fiction or sci-fi genre, which we already knew it was.

Despite its technical genre placement, Dick comfortably harkens back to his writings about people living their lives in the 1950s in California – only now it’s 1980 and their day-to-day lives are less immediately stressful. This only leads to existential stress, though.

By using a start-to-finish female narrator for the first time, PKD distances himself from the character only superficially; Angel is a stand-in for the author with her interest in religious people and issues – and ultimately her sense of fulfillment with those topics and desire to move on to the next thing.

A final statement

While it’s a sure thing that Dick would’ve written many more books had he lived (indeed, he left a novel called “The Owl in Daylight” unfinished), it’s fitting that “Transmigration” has the feel of a final statement of a segment of his life.

In chapter 13, Angel decides what she wants from a restaurant menu:

What I wanted was immediate, fixed, real, tangible: it lay in this world and it could be touched and grasped; it had to do with my house and my job, and it had to do with banishing ideas finally from my mind, ideas about other ideas, an infinite regress of them, spiraling off forever.

PKD could be writing about how he’s done with those wild, often sci-fi novels set in satirical dystopian futures. While I do miss the humor of his earlier works, Dick makes up for that absence by crafting a strong mystery, believably flawed characters and a heartfelt vibe of nostalgic reflection.

(Which isn’t to say this book is humorless, just that it’s more subtle. There is amusement to be gleaned from the difference between how the world sees the bishop and his actual, rather ridiculous nature.)

“The Transmigration of Timothy Archer” doesn’t put a bow on PKD’s learnings from the 1974 beam of pink light by any means; the identity of Bill/Tim remains unsettled. Yet Angel – along with the author – finds a measure of peace and contentment at the end.