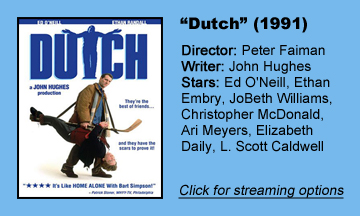

John Hughes’ other Thanksgiving movie, “Dutch” (1991), has that “other” status for a reason: It’s not as funny as “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” (1987). However, as I got to the end of this road-tripper, I realized I owe it a future rewatch, because it’s not trying to be as humorous.

Its interest is in the relationship between entitled kid Doyle (Ethan Embry) and potential stepfather Dutch (Ed O’Neill). I’ve been told this stuff will ring true to people thrown into such a relationship, but it’s frustrating how long it takes Doyle to turn into a nice kid. (It seems so wrong that Embry, later of “Vegas Vacation” and “Can’t Hardly Wait,” isn’t playing his usual sweetest-guy-ever.)

Another odd couple

“Dutch” is recognizably Hughesian. The writer is never afraid to try adult-child odd-couple pairings. A year earlier, a kid faces off against robbers and befriends an adult stranger in “Home Alone.”

And later in 1991, “Curly Sue” chronicles a homeless father and daughter. Also in that film, Hughes – whose characters’ troubles rarely involve money — tries to honestly dig into how the other half lives.

Whether he succeeds at that in director Peter Faiman’s “Dutch” is an open question. At one point on their journey from Doyle’s Georgia school to mother Natalie’s (JoBeth Williams) Chicago house for Thanksgiving, Dutch asks Doyle to pretend he doesn’t have $10 million coming his way from his father (Christopher McDonald, the specialist at smarm) when he turns 21.

The duo – played by actors displaying poor chemistry in a good way (if you know what I mean) — ends up in a homeless shelter for the night, but when you’re rich, you can only pretend to be poor; you can’t truly feel it.

A late-film revelation about Dutch’s construction-biz success further (accidentally?) drives home this point, right before they sit down to Thanksgiving dinner in Natalie’s mansion, prepared by a servant.

O’Neill can act

But the Dutch-Doyle relationship is in Hughes’ wheelhouse. O’Neill spent so much time on “Married with Children” that it seemed necessary to point out that he can actually act; this restrained performance must’ve been incredibly refreshing at the time.

As Doyle’s turn to niceness keeps being put off, Dutch has our sympathy as he tries to get through to the boy with everything from tough love to an impromptu fireworks show.

But this seemingly put-together lad truly is troubled; compare the car’s destruction here (a cry for help) with the equivalent moment in “PT&A” (over-the-top comedy) and the difference between the tones is underscored.

Still, “Dutch” delivers a gut-buster when Dutch’s cot keeps breaking in the shelter, leading to wide shots of people snapping awake in shock and one curmudgeon furiously shushing him. And when the pair hitches a ride from two prostitutes, the film gains momentum.

Doyle’s new experience – of talking to a girl – allows him to perk up in his chats with Dutch. It’s a strange turning point, but Dutch will take it, and viewers certainly will too.

Pure Americana

As a cross-country journey, “Dutch” is pure Americana with its gas stations, roadside diners and cheap lodges. It may be true that seeing how the other half lives isn’t the same as living it, but Doyle definitely sees it.

When he peruses the menu for something that “won’t make him puke,” he’s surrounded by a trucker sucking down every last piece of turkey gristle and a woman who doesn’t tap the ash off her cigarette. He’s too young to be grossed out by the world, but we can’t blame him.

“Dutch” is never hard to watch, and its points about how poor people deserve dignity are well taken, even if they are more pointed in “Curly Sue.” Hughes is interested in the Dutch-Doyle relationship here, so he tones down his comedy engine, revving it up only occasionally.

Stepchildren and stepparents might be the ideal audience for “Dutch,” especially if they can smile at themselves after the passage of time.