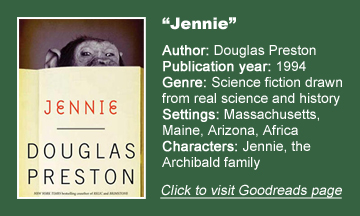

Douglas Preston starts his fiction-writing career with a novel that’s almost unrecognizably his own, when viewed from the lens of a quarter-century of imaginative sci-fi collaborations with Lincoln Child. “Jennie” (1994) is unlike anything else on his resume.

It’s deeply researched and concerned with hard scientific facts and discoveries – similar to his nonfiction works in that way – yet it is a work of fiction written in an unusual but effective style. Preston is the off-page “interviewer” and “researcher,” but we get the story of the titular chimpanzee raised as a human straight from the interviewees’ responses, journals and lab notes.

Species similarities

As we experience Jennie’s life in the 1960s and ’70s with the Archibald family (based on real-world accounts of chimps living with humans), Preston creates an air of foreboding and fatalism with tidbits of information slyly peppered in.

Jennie has never seen another chimp, and believes she is human. No chimp has lived past puberty with a human family. Chimps become more aggressive when they hit puberty. Their strength is four times that of a strong human man, and they have trouble reining it in.

“Jennie” is a puzzle where the answer is barely out of reach, yet there’s never any question that the Archibalds mean well. Hugo, Lea and Sandy are like Jennie’s father, mother and brother.

Sister Sarah provides an alternate perspective, never getting along with Jennie. Scientists and the pastor across the family’s New England street provide other POVs.

Preston digs into fascinating hard science. Chimps are our closest genetic relatives (other than the rare bonobo), and when Jennie learns ASL signs, it shows they are even closer than we thought.

She has empathy and cares for her family members, which is why they (and we) think of her as “she” and recoil when an interloper says “it.” (On a more chilling note, Preston points to Jane Goodall’s discovery that war and murder are very much present in chimp society.)

It’s fun to watch scientists’ arguments for why humans are distinct among the animal kingdom be shattered.

Differences provide tension

But once Preston establishes the similarities between chimps and humans, it’s the differences that provide “Jennie’s” tension. Jennie is brilliant by chimp standards, but is sort of like a mentally challenged human. There’s a lot she can do, but also a lot she’ll never be able to do.

While nurturing and teaching have their value, the most fascinating part of “Jennie” is what Preston reveals about “nature.” He posits that an unassailable difference between humans and chimps is our conceptions of freedom.

Although we started from a common ancestor, humans have valued freedom less as civilization has arisen; chimps still hold freedom as paramount.

The semi-slavery that we live under without giving it much thought – having a percentage of our labor earnings taken by governments, living in the physical structures of houses and apartments, laboring under the 8-hour structure of jobs – is intolerable to chimps.

This way of life is enjoyed by many humans, but some rebel against it. It’s neat how Jennie’s unchangeable nature nurtures Sandy’s view of what freedom is.

Happy times

This isn’t to say “Jennie” is all doom and gloom. That lurks in the background, but the novel’s momentum comes from happy and heady times (including visits to talk shows and state dinners!).

We can’t help but love Jennie when she’s playing her favorite game, “tickle-chase,” in the backyard with Sandy. Even when she makes messes or throws tantrums, we see endearing parallels to humans.

Beyond Jennie herself, the humans are thoroughly developed, flawed people. Hugo is an absent parent to Sarah, despite living in the same house; Lea is overwhelmed as Jennie’s primary caretaker; and Sandy is unsympathetic to his parents’ points of view. “Jennie” is a tragedy, but it’s a beautiful one, built on the love of a creature humans weren’t supposed to love.

It’s not a denigration to his career since then to say “Jennie” remains Preston’s best novel.