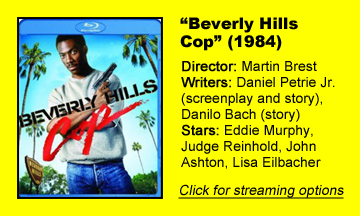

With Eddie Murphy making a full-fledged return to acting (“Coming 2 America” is coming soon, and “Beverly Hills Cop 4” is in the works), over three days we’re looking back at his most famous role, Axel Foley in the “Beverly Hills Cop” series:

Iconic song, character

Harold Faltermeyer’s “Axel F” is an iconic song of the 1980s, but I had forgotten how much this tune and similar sounds dominate “Beverly Hills Cop” (1984). All the usual cops-and-criminals traits are on display — including dangerous action, killing and swearing — but the soundtrack tells us this is a fun action romp.

It pairs perfectly with Axel Foley (Eddie Murphy), who is his own man if there ever was one, with a honking laugh so distinct that friend Jenny (Lisa Eilbacher) playfully makes fun of it.

It’s interesting to note that director Martin Brest’s film introduces our hero as a reckless Detroit cop who steals an impounded semi truck to entrap small-time cigarette thieves without the chief’s permission. Before Axel secures the criminals, they tear up Detroit (even more than it already is) in the truck, doing untold property damage; if no one is killed in this (admittedly impressive, cinematically) chase, that’s sheer luck.

One-liners, comebacks

Axel is not a put-upon detective whose bosses don’t understand his brilliance; he is a truly reckless smartass. And he knows it: “I don’t think cost is the issue here, sir,” he tells his DPD boss (Gilbert R. Hill). “I think the issue should be my blatant disregard for proper procedure.”

Axel regularly spouts one-liners and comebacks from Daniel Petrie Jr.’s screenplay, and effortlessly throws off the tailing by Beverly Hills detectives Billy (Judge Reinhold) and Taggart (John Ashton) as he pursues the case of his best friend’s murder.

We like Axel not because he’s a good man – indeed, he’s a former criminal and still considers the shady-as-hell Mikey (James Russo) his bestie – but because he’s free to do as he pleases. He lacks the part of his brain that asks for permission.

And, like the actor who plays him, he’s funny. In a standout scene, Foley gets past a private club host by affecting a gay voice and pretending to be the villain’s lover. All told, Axel is so sharp and likable – but still somehow down-to-earth — that we tend to say “Well, he’s not that bad of a guy.”

Funny even beyond Murphy

Plus, “BHC” is a comedy even beyond Murphy’s shtick. Bronson Pinchot plays a tea-obsessed, heavily accented art gallery host with absurd glee, and Damon Wayans has a small but ridiculous role as an effeminate fruit seller who gifts Axel with three bananas.

Although “BHC” gives off these signals that it’s not to be taken seriously, it has a by-the-book story at its core, just as the DPD and BHPD operate by the book. After Taggart punches Axel at the precinct, BHPD Lt. Bogomil (Ronny Cox) gives Axel the opportunity to press charges for assault.

In the climactic shootout where the baddies use high-powered machine guns, Billy is anxious to jump up and announce that they are under arrest. The villains are also all-business, particularly Jonathan Banks – later Mike on “Breaking Bad” – as the grim-faced henchman.

Later films influenced by “BHC” – “Lethal Weapon,” “The Last Boy Scout,” “Bad Boys” — view internal police operations as further outlets for chaotic comedy, but Petrie Jr. (working from a story he developed with Danilo Bach) plays this stuff straight. He either trusts the police himself or he’s crafting a Pollyanna world where they are totally trustworthy.

Loose cannon

The Detroit and Beverly Hills police departments are broadly competent and free of corruption, and it’s the hero cop who is the loose cannon. For a half-second, I suspected BHPC Chief Hubbard (Stephen Elliott) might be in league with Victor Maitland’s (Steven Berkoff) bearer-bond/drug operation, but he’s not.

Hubbard just wants things done by the book, and “BHC” actually makes an argument that things can’t always be done by the book out on the mean streets (be they dirty like Detroit or pristine like Beverly Hills).

Quick decisions and actions are necessary to, for example, rescue a hostage in the climax at Maitland’s estate. It’s easier to finesse reports than to answer for decisions and actions that aren’t by the book.

“BHC” makes a case that cops shouldn’t be involved in such complex operations as the Drug War, and that there’s no place for reckless ex-criminal cops like Foley if the goal is to make cities safer.

But that commentary is accidental and beneath the surface. It has no chance of penetrating Axel Foley’s personality and accompanying theme song.