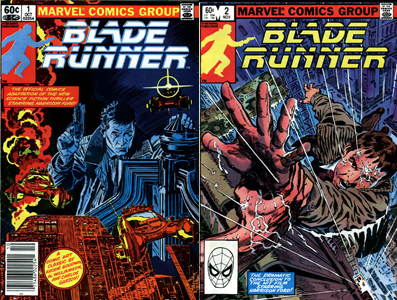

Both “Blade Runner” and comic books have drastically increased in prestige since 1982. When I consider the two-issue movie adaptation (October-November 1982) today, I think of it as a prestigious project: legends Archie Goodwin (writer), Al Williamson and Carlos Garzon (artists) adapting a classic SF film.

‘A comic art classic’

In reality, of course, Marvel fibs on its Issue 2 cover by calling “Blade Runner” a “hit film.” It famously bombed upon its release. (On the other hand, Issue 1 says “A comic art classic.” That jumps the gun, but it’s accurate today.)

Movie adaptations were declining in mass appeal by 1982. I know this trio’s work from the adaptations of “The Empire Strikes Back” (1980) and “Return of the Jedi” (1983), where we can measure that decline in popularity: “Empire” was six issues, “Jedi” only four.

“Blade Runner” (1982)

Marvel, 2 issues

Writer: Archie Goodwin

Pencils: Al Williamson, Carlos Garzon

Inks: Al Williamson, Carlos Garzon, Dan Green, Ralph Reese

Colors: Marie Severin

As I noted in my reviews of those comics, “Jedi” suffers from being shorter. So “Blade Runner” must feel incredibly minimized from the screenplay by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples, right?

Surprisingly, not at all. Goodwin does yeoman’s work – which we now recognize as a master craftsman’s work – in making “Blade Runner” flow naturally through two issues. Plus, he gets lucky in that “BR” naturally adjusts to a tighter framework: It’s not plot-heavy.

Setting aside the worthiness of the film’s voiceovers, there’s no question the comic benefits from Deckard narrating a lot of the events. It saves space and also fits with the style.

Skillful adaptation

To cite an example of Goodwin’s skill, consider Deckard giving Rachel the Voight-Kampff test at the Tyrell building. We had already seen Holden give the test to Leon, so we know the gist of the questions. For this interview, Deckard simply tells us: “After more than a hundred questions … I wanted to talk to Tyrell in private.”

So Goodwin compresses the script without sacrificing any story, and even the mood remains. Although the pages aren’t overstuffed with panels, there is a fair amount of text to read, so we naturally turn the pages slowly.

Not surprisingly, there are no “bonus scenes” in these two issues like there are in some other adaptations (which are often prepared without the writer seeing the final cut). But we see two moments before they found their finished form.

Both involve Ray Batty. He tells Tyrell, “I want more life, you pompous ass!” (In the film, he calls Tyrell either “father” or “f***er,” depending on the version.)

And Batty’s final line is “All those moments, they’ll be gone,” as per the shooting script. We miss out on actor Rutger Hauer’s poetic contribution that became arguably the most famous last words in cinema history: “All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. … Time to die.”

Vintage Williamson

As for the art, Williamson – as is his wont — draws Harrison Ford and other actors from stills, yet “BR” isn’t a static experience. Well, maybe Rachel looks static, but that fits with the character.

For some bizarre reason, “Blade Runner” hasn’t been reprinted since 1982, so you’ll have to buy the original two issues (which you can do for less than $20, although the days when you could grab them for 20 cents each are past) or the combined edition (which costs significantly more).

Depending on your taste, this is good or bad. A crisp, re-colored update would be nice; I like reading the Eighties Marvel “Star Wars” comics (some of which came from Goodwin and Williamson) in Dark Horse’s remastered quality-paper volumes.

But you do get the smell of an old comic, plus you can laugh at the incongruous ads aimed at kids. The ink has soaked into the page, leading to a situation where you have to get close to it to appreciate Garzon’s background details and even to read the words.

That will slow you down. But like I say, “Blade Runner” was meant to be savored anyway.