In the late 1950s, Philip K. Dick found a career as a science fiction writer, and quickly became quite good at it, delivering several classics. Even his non-classics are beloved by PKD fans, sometimes because of their uniquely Dickian absurdities.

But he started his career – or rather, tried to start his career – in down-to-earth fashion, chronicling blue-collar lives in California (except for one in Idaho and one in China) from 1950-60. These nine books – variously labeled “non-SF,” “Fifties,” “realist,” “straight,” “mainstream” or “literary” novels — would eventually be published in 1975 (the only one PKD lived to see), and then 1984-88, and then 1994 and 2007. Because of reprintings, all are now easy to acquire at a reasonable price.

Not merely curiosities, all nine novels will appeal to PKD die-hards, ranging from “for fans only” at the bottom to legitimate masterpiece at the top. Here are my worst-to-first rankings. Click on each title for my full-length review.

9. “Gather Yourselves Together” (written in 1950, published in 1994)

PKD’s first-written (and second-to-last-published) novel is his weakest of the non-SF works. It’s also least recognizable as a PKD novel because he hasn’t yet found his own style. It’s more like the dialog-heavy “Franny and Zooey,” serialized by J.D. Salinger starting in 1955. Two men and two women verbosely and somewhat romantically circle around each other in an evocatively isolated location: a factory in China, preparatory to the handoff from the U.S. to the new Communist government.

In the closing pages, PKD – through young Carl, who is exploring political factions – comes out against the violence inherently needed to enforce Communism. If a reader is generous, the novel is a Communism metaphor, about four people whose co-existence is tense – sometimes verging on violence — because it is forced. Not as bad as Lawrence Sutin’s grade of “Not Worth Grading” on a scale of 1-10, “Gather” is impressive for a young writer’s first novel. PKD aficionados should cherish the fact that it was eventually published.

8. “The Broken Bubble” (1956, 1988)

The core of this novel is a fascinating love quadrangle. Art represents PKD in the wake of his first shotgun marriage, as he’s bored by Rachael and drawn to the older Patricia. Meanwhile, Patricia’s wife Jim – a teen-music radio DJ – is into young Rachael. So we have an amusingly agreeable love quadrangle, although tension hangs over everything since this is the Fifties rather than the Seventies, and everyone enables bad traits in everyone else.

“Broken Bubble” ranks low on this list because it’s absurdly overstuffed. It tacks on subplots about draft-avoiders, conspiracy theorizing, a high-tech remote-controlled car, and a white-collar convention where men kick around a nude female performer encased in a plastic bubble. The whole is less than the sum of its parts as a piece of literature, but the core fractured relationships remain compelling.

7. “In Milton Lumky Territory” (1958, 1985)

Unquestionably the best book ever written about typewriter salesmen in 1950s Idaho (which is the butt of the joke here as much as in the 2004 film “Napoleon Dynamite”), “Milton Lumky” is unusual for PKD in its mellowness. The author introduces it as a “happy” novel. Husband Bruce encounters just as many tests in his marriage (to his former schoolteacher Susan, 10 years his elder) and his job as other PKD protagonists. But Bruce doesn’t fly off the handle as quickly – he sticks with the marriage and the job longer.

The book is livened up by its big-personality title character, Idaho’s dominant typewriter salesman. The author provides a twist toward the end, centered on the question of “What’s real?” that he’d return to in his SF works. It cuts into the truth of what’s happening between Bruce and Susan enough to put “Lumky” in the lower part of my rankings, but I do find it the most relaxing read of the realist novels.

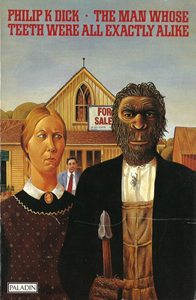

6. “The Man Whose Teeth Were All Exactly Alike” (1960, 1984)

If “The Simulacra” is PKD’s “grab-bag” sci-fi novel (in the sense that it’s stuffed with his favorite themes), “Man Whose Teeth” is the realist-novel equivalent. It features men navigating changing gender roles, the idea that suburban life is an exhausting competition with your neighbors, and examinations of racism and abortion.

The reason for the title doesn’t emerge until deep into the book. Walt aims to place the fake titular skull on frenemy Leo’s property to make him look bad. It’s not narratively necessary that PKD digs into archaeology, anthropology and history more so than any other of his works. But his writings about “dawn man” and local water-utility politics are quite engaging. “Teeth” is a great novel for those already sold on PKD’s penchant for grand absurdity, not so much for someone new to the author.

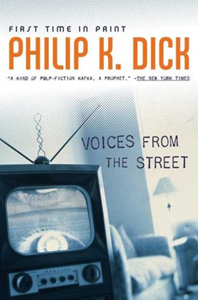

5. “Voices from the Street” (1952, 2007)

PKD’s thicker and more manic answer to Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye” (1951) follows Stuart Hadley, the 20-something second-in-command at a TV sales and repair store who – in a parallel to PKD’s first marriage – “settled down” before he knows what he wants or even who he is. In a biting slice of dark comedy, Stuart’s relationship with his wife is so flimsy that he’s terrified he wouldn’t recognize her out of context.

“Voices” is an aggressive and angry novel, and not only when focusing on Stuart. PKD would effectively mellow down characterizations of boss Jim and repairman Olson when cannibalizing them for future works (“Humpty Dumpty in Oakland” and “Puttering About in a Small Land”), as he didn’t know this one would be published. (Indeed, it’s his last novel to see publication.) But one brash personality – Stuart’s effortlessly domineering brother-in-law Bob – is perhaps the most crisply harrowing side character PKD ever wrote.

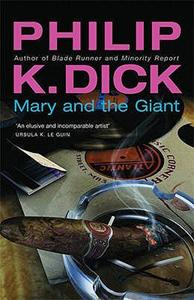

4. “Mary and the Giant” (1954, 1987)

I suggest this be read as a gender-swapped companion piece to “Voices.” In one of the few novels with a female protagonist from this author known for failed marriages and obsessions with pretty dark-haired women, PKD spends the length of the book trying to understand Mary. Even if PKD doesn’t understand her, the end result is at least an honest portrayal of how men (no less than four of them) fail to understand women.

Mary’s ephemeral nature (to an outside observer) — along with her anxiety, inferiority complex and (like “Voices’ ” Stuart) lack of self-definition – has her blundering through her 20s. Another rarity: One of the sad sacks does get the desired girl in the end, as PKD decides “What the heck – the nice guy won’t finish last this time.” It doesn’t seem earned in the moment, but upon reflection, it fits with how Mary stays out of the reach of predictability from start to finish.

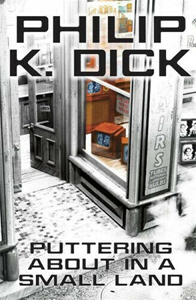

3. “Puttering About in a Small Land” (1957, 1985)

Serial monogamist PKD often found himself married to one woman and longing for another. That’s not a situation that will gain much sympathy. But however morally uncomfortable the situation is, it is a real-life scenario, and the author explores it honestly from the perspective of alter-ego Roger Lindahl. The stressed-out blue-collar radio and TV salesman is obsessed with sexy simpleton Liz Bonner, with whom he spends time as they drive their respective children from L.A. to a private school in Ojai.

The novel is arguably overwritten, but it does thoroughly illustrate everyday stresses like busy-highway and mountain-backroad driving. PKD shows how a person can follow the marriage-and-children playbook yet be tempted to sabotage it. Roger might not be sympathetic, but he’s very human.

2. “Confessions of a Crap Artist” (1959, 1975)

Although this was PKD’s seventh-written realist novel, it was the public’s first taste (and it’s the only one of the nine to be adapted for the screen – the inferior but interesting French film “Barjo”). It’s an excellent choice to introduce PKD’s non-SF work, as the author probes people’s inner thoughts to show why insane moments come about – such as husband Charley punching wife Fay, feeling humiliated from buying tampons for her. He’s caught between old-school masculinity and the new normal.

For her part, Fay is psychologically unstable – to the point where she’s getting counseling (more noteworthy then than today). And a younger man, Nat, is next in line after Charley to get caught up in the love-hate cycle with Fay. The title character, Fay’s live-in brother Jack Isidore (who the author would repurpose as the toy-maker in “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”), has brazenly nutty habits such as collecting milk bottle caps. But he also functions as a reliable wallflower observer of how the “normal” people are just as crazy as him – only in more mainstream ways.

1. “Humpty Dumpty in Oakland” (1960, 1986)

PKD’s last-written realist novel is also his best as he builds on what he’s learned from previous efforts. It explores titular sad sack Al Miller, the poor schmo who doesn’t know the secret handshake in life. He scrapes by as a crooked used-car salesman, fakes his way into a job as a record producer, and generally bumbles around looking for a break. Mechanic Jim Fergusson is his frenemy foil, a successful wheeler-and-dealer who might be prone to a fatal middle-age heart attack. The always prescient PKD previews his own life here, with Al representing his current lot and Jim his future situation.

Early on, the book is a vibrant portrait of the Bay Area’s growth into a sprawling metro area, and at the end we get a dramatic convergence of characters worthy of the cinema — Quentin Tarantino would admire how it comes together. In between, “Humpty Dumpty” is a remarkably sober examination of paranoia from a paranoid author.

Click here to visit our Philip K. Dick Zone.

Main image by Adrien Villez from Pixabay.