Among the Philip K. Dick estate-licensed works of recent years, the easiest to miss is certainly 2021’s five-issue comic-book miniseries from AfterShock, “Nuclear Family.” But PKD fans should check out this adaptation of “Breakfast at Twilight” (1954), my pick for the best short story from “The Collected Stories, Vol. 2.”

That’s not to say you’ll get a straight adaptation. If there was no mention of PKD in the credits (as it is, AfterShock promotes the PKD connection surprisingly minimally), casual readers would miss the “Breakfast at Twilight” connections. Serious PKD fans would spot it, and maybe think this story comes close to stealing from it.

The adaptation’s approach reminds me of TV’s “Man in the High Castle.” Writer Stephanie Phillips uses PKD’s story as a springboard, and key thematic points as tunnels to explore. Dick’s story is 14 pages long, but “Nuclear Family” can be as long as it wants to be.

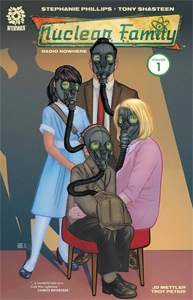

“Nuclear Family: Vol. 1 — Radio Nowhere” (2021)

Five issues, AfterShock

Writer: Stephanie Phillips, based on Philip K. Dick’s short story “Breakfast at Twilight”

Pencils: Tony Shasteen

Colors: JD Mettler

It looks like it will stop at five issues (collected in a TPB as “Vol. 1: Radio Nowhere”) as apparently AfterShock’s sales numbers weren’t high enough, although Phillips does leave a final image that could lead to a next chapter.

Return to nuclear fears

In addition to the looming cloud of nuclear-bomb fears common to PKD stories, “Breakfast’s” theme is that bad things in the world don’t have a start date. Rather, they are an ongoing process. At some point, the dollar will likely collapse, and people will point to a date when it “happened.” But in actuality, we are currently living amid the process of the dollar’s collapse.

Likewise, Dick recognized in 1954 that – even though things seemed superficially good in the USA – he was living amid a process of events that would lead to a nuclear-bomb-driven World War III. (It didn’t happen in his lifetime, and it still hasn’t, but strictly speaking, it still could. Humans think about nuclear warfare less now because it’s an older fear, displaced by newer ones.)

Dick’s story touches on how the American military, the ostensible good guys, can be the most terrifying apparatus in the world if you are labeled as its enemy. In the case of this yarn, the label is Russian Communist infiltrators. This happens to “Nuclear Family’s” McClean family (changed from McLean).

In both versions, we start rather than end with a Shyamalan-esque twist. A suburban Midwestern family is getting ready for work and school (in 1958 in the comic, 1968 in the story), then soldiers aggressively invade their home. The family learns they’ve jumped forward in time (to 1968 in the comic, 1980 in the story).

The slight timeframe change by Phillips allows penciler Tony Shasteen and colorist JD Mettler to convey the (misleadingly) wholesome Fifties. Tim is a car salesman who’s not quite as sad-sackish as the average PKD leading man, Linda is the upbeat housewife, Robin is the mildly rebellious (i.e., cigarette-smoking) teen girl, and Henry is the boy whose playtime involves toy guns – although he has a tinge of the safety-craving kid from 1955’s “Foster, You’re Dead.”

Back to the post-apocalypse

After the time jump, Stasteen and Mettler evoke post-apocalyptic imagery from baked-out red-and-brown wastelands to sterile underground labs. The latter location, ironically, has the scariest stuff, as Phillips does PKD one better.

She reasons that if governments can dream up and follow through on nuclear bombs, then they can continue to do horrific things after the bomb. PKD’s post-bomb imaginings are relatively tame and reflective, as he believed humanity would mellow out and recalibrate – as seen in “Dr. Bloodmoney” and “Deus Irae.”

“Nuclear Family,” though, finds the U.S. government experimenting on its own citizens in an attempt to create the perfect soldier (for the military’s purposes, not from the individual’s POV – as you’ll see when this new horror is unleashed).

The government’s secret experiments on St. Louis-area citizens happened a year before Dick wrote “Breakfast at Twilight,” but he didn’t know about it (the facts were exposed 40 years later). As with many of his stories, Dick takes a Pollyanna-leaning approach toward the soldiers (though not the overall structure of the government).

Commissioner Douglas, while certainly the McLeans’ adversary, does use a logical equation to decide their fate: If they are not Commie spies, they can join the military state; if they are spies, they will of course be killed.

Harsher critique of the state

“Nuclear Family,” on the other hand, finds military platoon leader Dan (Tim’s fellow Korean War vet bestie in the original timeline) torturing Tim for Commie-spy secrets. As with the villains of TV’s “High Castle,” it’s apparent that once it’s clear Tim won’t spill any secrets, they’ll kill him and his family. This operation is about procedure and efficiency, not humanity or nuance.

In addition to the unflinching critique of the U.S. military state – enhanced by satirical “fear your (potential Communist) neighbor” propaganda in the trade paperback’s bonus section — the comic includes a subtle puzzle mystery in the background.

Phillips writes it smartly enough that I know it’s not an inexplicable quirk that Dan doesn’t recognize Tim in the future timeline. Rather, she is hinting at the nature of the time travel – something crucial for putting the pieces back together. And when Issue 5’s goal has played out – the McCleans’ attempt to return to 1958 – “Nuclear Family” leaves us with another brain-teasing image.

The “one last twist” reminds me of “Ubik,” so if “Nuclear Family” ends here, it’s a suitably Dickian complete work. It’s not a narratively faithful adaptation of “Breakfast at Twilight,” but it’s one that mostly respects Dick’s point of view. It does go more anti-state than Dick would have, but that’s because PKD (for all his prescience) was a little naïve in 1954; he wouldn’t be so naïve in 2021.

If “Nuclear Family” does emerge from the ashes for a second volume, sign me up.